Israel’s military operations always have a name. As a mark of his achievement in June 1967, Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin was granted the honour of naming the war in which he had masterminded such a significant victory. With typical understatement, Rabin cast aside the dramatic and bombastic suggestions of his staff and named it simply ‘the Six-Day War’.

In Matti Friedman’s book, names and their absence are a recurring theme. In this powerful memoir he chronicles what he calls the forgotten war that had no name. To be precise, the intense conflict between the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) and Hezbollah in southern Lebanon was not a new war but rather the long tail of the 1982 Lebanon War, termed ‘Operation Peace for Galilee’. What started in the 1980s as a fight against the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) morphed into something completely different. The Palestinian ‘state within a state’ was dismantled with the PLO leadership escaping to Tunis. But Israel took a grave gamble and picked a side in the civil war hoping to benefit from a future strategic alliance with Lebanon’s Christian Maronites. When the violence spiralled out of control Israel was sucked into the horror of Lebanon’s civil war. A series of disasters, massacres and miscalculations led to the ousting of Defence Minister Ariel Sharon and ultimately the resignation of Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Israel slowly redeployed south to a thin belt of Lebanese territory it named the ‘security zone’. The mission was to contain Hezbollah on Lebanese territory within a buffer zone, and thereby protect Israel’s northern border from terrorist incursions.

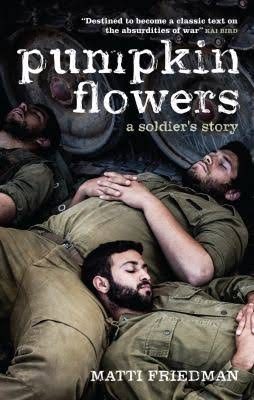

Israeli soldiers were positioned across the security zone in a network of hilltop bases. It is one of these bases, called ‘the pumpkin’, or ‘dlaat’ in Hebrew, to which the book owes part of its name. In an effort to distort language and sanitise a difficult situation the IDF had a penchant for code names rooted in the natural world. All the bases in southern Lebanon were named after fruits and vegetables while casualties were called ‘flowers’. This explanation early in the book only adds to the surreal story.

Friedman commands his material with great skill. He ignores the politicians and the generals and focuses at ground level on the lives of young soldiers, mere teenagers led by officers only a few years older. The story unfolds through their eyes, generating deep empathy and understanding, which is amplified when they are attacked and killed. The pace is set by events, brilliantly capturing the reality of life as a combat soldier while simultaneously managing to make the reader laugh with anecdotes of young men in their prime who, instead of having fun, are stuck in a strange land facing an adversary who desires their destruction. Time moves slowly and often their greatest enemy is mind-numbing boredom. Their lives are largely monotonous and uneventful, always preparing for an emergency through repetitive drills, which are punctuated by brief bursts of terrifying intensity.

The book has three distinct parts. Firstly, the period leading up to the tragic night when two Israeli helicopters transporting soldiers into the zone collided in mid-air killing 73 young men, an event that magnified the public pressure inside Israel to end Israel’s presence in the security zone. Secondly, Friedman’s personal story of living as a combat soldier in the pumpkin; and finally his fascinating mission to visit Lebanon on his Canadian passport and tour the Lebanese villages that surrounded the base, including his poignant return to the now abandoned outpost. Together these combine to create a compelling collection of memoirs eloquently describing the thoughts, feelings, ambitions, and fears of a generation of young men.

Friedman transports the reader back to a world before smartphones and social media as well as to a Middle East before 9/11, and ISIS. The soldiers he depicts are from Generation X, sons of baby boomer parents and military commanders who had a clear sense of what a real war (and victory) looked like. They were brought up on stories of heroism from the Six-Day War and Yom Kippur War, combat that included parachute drops and armoured columns whose participants were rewarded with medals. Even in the 1990s, when the book is set, the best military minds believed the real threat to Israel came from the Syrian army, and all training was focused on preparation for a full-scale war with it.

Combat in the hostile territory of southern Lebanon was looked upon simply as fighting a terror group to protect the north of Israel. While patrolling and maintaining the ‘security zone’, the soldiers had to deal with mortar fire, hidden roadside bombs, Claymore mines, Sagger missiles and ambushes. Yet these events went largely unnoticed ‘back home’ and are already forgotten by many Israelis.

Friedman argues that Israel did not properly understand Hezbollah and what it represented. Yet with a dose of hindsight it is clear that this small conflict was the petri dish for the mode of combat later seen in Iraq, Afghanistan and across the Middle East. The crude roadside bombs hidden in plastic boulders purchased at garden centres were precursors of the modern improvised explosive devices; and when a small group of Hezbollah fighters attack the pumpkin purely to film themselves hoisting their flag and trashing the Israeli one, the shell shocked soldiers are baffled. When the film is broadcast across the world and communicates a compelling message that the ‘invincible’ Israelis are just boys that can be easily beaten, the impact is like an earthquake, shaking Israeli society and its military into a clearer understanding of the nature of the new enemy. Incidents such as these were a precursor to ISIS’s mastery of social media. It is also at this time that a three-way alliance between Syria, Hezbollah and Iran intensified. A deadly combination that has caused so much suffering in Syria today.

My older brother served as an officer in southern Lebanon and also spent time at the pumpkin. As a doctor his job was to join patrols and rescue the wounded from the field, no matter how intense the fighting. Although his experience was different to Friedman’s, he too had static periods in fortified positions in addition to having to run the local hospital in Bint Jbeil and direct a healthcare system for thousands of Lebanese civilians. We both read Friedman’s book during the summer and recalled his bizarre weekends on leave in Tel Aviv. When he told people he was serving in Lebanon there was always an awkward silence. No one knew what to say nor had any comprehension of the horrors taking place just over the Lebanese border a few hours drive to the north. I recall one eventful Saturday night when drinks at a bar led to a party and then a gathering on the beach that lasted well into the early hours. When we saw the time and decided to call it a night, I still remember the pain in his eyes because the fleeting fantasy world of carefree living was over and it was time to head back to war. Only minutes after we returned home he was transformed – back in his officers fatigues with an M16 over his shoulder, he said goodbye and began his journey north. I’ve never forgotten that morning because I realised I might never see him again. Thankfully he survived unscathed, but many of his comrades and friends did not.

Matti Friedman has succeeded in his mission to tell the story of and analyse a conflict that has been forgotten by many and to pay tribute to all those who lost their lives or suffered physical injury and mental trauma. The postscript to Friedman’s book is that in 2000 the IDF withdrew from the security zone and destroyed the outposts it defended for so long. Hopes held by many Israelis for a new peaceful Middle East were dashed as the Palestinian Intifada broke out and Hezbollah continued to attack Israel, which ultimately escalated into the 2006 Lebanon War and the deaths of many more young Israeli soldiers in the villages and hills of southern Lebanon. In the years since Israel’s withdrawal, Hezbollah has become a semi-state actor, possessing a military force larger than many NATO countries, and is currently active in the Syrian civil war on behalf of the Syrian regime.

Comments are closed.