Jean Améry is best known in the anglophone world as a Holocaust survivor and author of At The Mind’s Limits, an Auschwitz memoir hailed by the critic Irving Howe as ‘the testimony of a profoundly serious man’. But in the 1960s he was also the outspoken left-wing critic of left-wing antisemitism in Western Germany and it is this Améry who Marlene Gallner’s important essay makes available to us as a moral and intellectual resource today.

The Shoah-victim Jean Améry, author of the searing memoir At The Minds Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and its Realities, was also an extraordinarily sensitive critic of the German post-war society and of what we have learned to call the ‘new antisemitism’. When, in the 1960s, anti-Zionism grew rapidly in the German public discourse, especially within the left-wing student movement, Améry published several essays on the relationship between antisemitism and anti-Zionism. ‘Anti-Zionism contains antisemitism like a cloud contains a storm’, he wrote in the German newspaper Die Zeit (Améry 2005a: 133). He was the first to publicly address left-wing antisemitism in Germany. His essays give eloquent voice to contemporary concerns and – in their radicalism and their ability to penetrate the inner life of the relationship between antisemitism and anti-Zionism – are in advance of many contemporary contributions. This essay contributes to the work of making Améry’s acute intelligence and moral urgency available as a resource today.

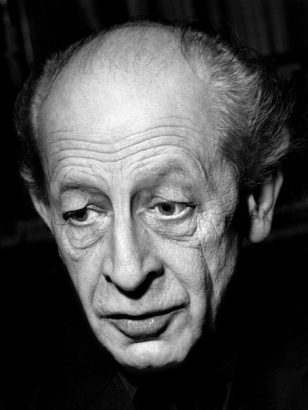

Biography

To fully comprehend Améry’s work it has to be situated within his personal history. He described himself as the ‘political and Jewish Nazi-victim that I was and am’ (Améry 2002: 16). His reflections on the experience of being exposed to a murderous collective and on the persistence of suffering as a Shoah-victim, course through all his work.

Améry was born in 1912 as Hans Mayer in Vienna. His father was proud of his old Vorarlberg Jewish descent yet Améry himself grew up non-religious. After an unsteady but happy childhood and youth in the Austrian Salzkammergut and Vienna he took his first steps as a writer and publisher. However, Améry soon faced discrimination and persecution and so in 1938, together with his wife, he fled to Brussels. Two years later, Améry was imprisoned in an internment camp in southern France. After his successful escape back to Belgium he joined a communist resistance group, but in 1943 was recaptured and subsequently tortured by the Schutzstaffel (SS) in Breendonck for his political opposition. When it became apparent that Améry was not only a political opponent of the Nazis but also a Jew, he was deported to Auschwitz and later on to other concentration camps. In 1945 he was liberated by the British Army from Bergen Belsen camp and he returned to Belgium where he began his struggle to cope with being a Shoah-victim. One consequence of that struggle was that he changed his name to Jean Améry.

He never returned to live in Germany or Austria but nonetheless remained a perceptive observer and critic of the German post-war society. It was not until 1966, when Améry was already 54, that the publication of Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne brought his writings to a larger audience. Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne, available in English translation as At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities is a sharp and unforgiving reflection on his experiences as a Nazi-victim. What makes Améry’s thinking so unique is that he branched out from the solely historiographic terrain of grasping National Socialism and took one step further to describe the moral-philosophical dimension of the Shoah and its aftermath.

After Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne, his newly gained recognition allowed Améry to publish his own explicitly political interventions about contemporary social trends, especially what he saw as the failure to properly confront the Nazi past and the appearance of a new face of antisemitism. With the exception of his writings on suicide, all his political work now centered on the new antisemitism and the importance of the Jewish State.

Israel and the Jews

Although Améry was not religious and had no connection to Israeli culture or language, the existence of the State of Israel was for him ‘more important than any other’ (Améry 2005a: 134). For him, Israel meant that Jews, wherever they lived, could find shelter from antisemitism, which was crucial after the experience of Auschwitz. He defines being a Jew not by religion or race, but by the common threat of antisemitism. It is a distinctively negative definition.

In Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne Améry described the unbearable tension between what he calls the compulsion and the impossibility of being a Jew. Not seeing oneself as a Jew, yet being made one ‘from the outside’, so to speak, constitutes the tension. It was not until the anti-Jewish racial laws enacted by the Nazis in 1935 that Améry fully understood that it was not his choice to define who is and who is not Jewish, but rather the choice of the antisemite. This reversal was not new, but the Nuremberg Laws gave an alarming new dimension to it. After the experience of the Shoah Améry never again trusted promises to protect the Jews. He remained wide-awake and could not cast off his seismographic sensitivity to the continued, if disguised, existence of antisemitism.

Améry offered two reasons for the ‘existential binding’ every Jew has to the State of Israel, whether he believes in Zionism or not (Améry 2005d: 165). First, Israel allows Jews not to depend on the external image imprinted on them. ‘It is the country where the Jew may be a farmer not loan shark, soldier not pale scribe, craftsman and not agent.’ (Améry 2005d: 165). This also implies for all Jews in the diaspora. Israel is the reason that enables them to be equally humans like their fellow citizens. Second, antisemitism, and threat of death it carried, did not disappear when the allies defeated the German death machinery in 1945. Améry did not suggest that every Jew should leave their native country and emigrate to Israel. His concern is the ‘possibility to find shelter’ (Améry 2005d: 166). If the Jewish State perished it would ‘leave her inhabitants nothing left but the butcher knife of the enemy’ (Améry 2005d: 167).

Antisemitism and anti-Zionism

I have already noted that Améry wrote in 1969 that ‘Anti-Zionism contains antisemitism like a cloud contains a storm’ (Améry 2005a: 133). Anti-Zionism was the new ‘honorable antisemitism’ that was now turned against Israel as the object of the same old and dangerous resentments (Améry 2005a: 133). The ‘emotional infrastructure’ and the psychological mechanisms of the antisemites remained the same (Améry 2005a: 133f). Antisemitism, to Améry, had nothing to do with the Jews and everything to do with the antisemites who were engaged in psychological projection.

Améry observes that the victim of antisemitism suffers, while the antisemite, the one with the actual psychological ‘disorder’, does not feel psychological strain: ‘I know that what oppresses me is no neurosis, but rather, precisely, reflected reality.’ (Améry 1980: 96) In psychoanalytic terms, antisemitism may be understood as an illness. And yet, it is no actual disorder because the antisemite is never impaired by it. It is modern society itself, which dialectically brings the antisemitic mindset forward. For the potential victim of antisemitism the choice is either an accommodation with or a revolt against this reality. However, he or she always has to expect what lies in the wait. Hence Améry writes his warning: ‘But since the sentence passed on me by the madmen can, after all, be carried out at any moment, it is totally binding, and my own mental lucidity is entirely irrelevant.’ (Améry 1980: 96)

After the Shoah, Jew-hatred changed its constitution. While physical attacks on Jews still existed, and are even increasing in recent years, it’s most virulent form today is anti-Zionism. It is not as easy to recognise, although the motives and even the stereotypes remain the same. Adapted to present-day circumstances and articulated in ways that are socially acceptable, at least in certain circles, antisemitism today is often the storm contained within the cloud of anti-Zionism. While open hostility to Jews remains on the far right and Islamic parts of the political spectrum, anti-Zionist resentment in Western countries is widespread. The new antisemite refuses to see himself as an antisemite. He proudly identifies as an anti-Zionist and thinks that thereby he has preserved his honor. But Améry points out that ‘the classical phenomenon of antisemitism takes a new shape. The old continues to exist. That is what I call co-existence’ (Améry 2005a: 131). Furthermore, he sees the new antisemitism today as more dangerous than the old, right-wing antisemitism that was and still is, easy to identify. In the 1960s Améry was reminded of National Socialist Europe: the call for the death of Jews, this time Zionists, was getting louder. He doubted that historical education could help abolish antisemitic prejudice because ‘anti-Zionism is nothing else than the update of the age-old, ineradicable, completely irrational Jew hatred’ (Améry 2005d: 162).

Antisemitism of the Left

Améry was utterly shocked to see that it was first and foremost the Left that supported this new antisemitism. He had always seen himself as part of the radical Left, at a time when leftist groups were the only ones to actively oppose antisemitism. And now his closest allies were betraying their own principles. Thus his loss of trust in the world as a Shoah-victim was reinforced 20 years later as a politically homeless leftist. His involuntary yet necessary estrangement from the Left makes his critique all the more poignant.

By the 1960s, left-wing antisemitism was no longer only a phenomenon of Soviet loyalists. Now it was embraced by the independent, so-called New Left. In the years immediately after the Shoah, the German public was relatively well-disposed towards the young Jewish State, though Améry believed that this was a cheap way to assuage guilt feelings. But in the 1960s, he describes how a gasp of relief could be felt in Germany in response to the rise of anti-Zionism. Finally, Germans could blame the Jews as oppressors, finally they could feel morally superior (see Améry 2005a: 133).

‘The left-wing student movement in Western Germany was a reaction against the conservatism of the previous two decades. The Auschwitz-trials in Frankfurt saw many young Germans begin to openly question the Nazi-past of the older generation, but they did not, as they should have done, break with their fathers. Pacifist views spread throughout German society while at the same time popularity of the Palestinian “liberation” struggle grew. The Six-Day War, in which Israel took over the West Bank from Jordan and Gaza from Egypt, was abused as a justification to now blame Israelis as the cruel persecutors. It was a rationalisation; a welcome opportunity to utter long suppressed reflexes.’

In modern antisemitic ideology, the moral mantra of the Left – to always be on the side of the weak against the mighty – gets upended. The antisemitic delusion attributes enormous power to the Jews, and the new antisemitism repeats the delusion for Israel. While Israel is faced with annihilation at the hands of hostile neighbours that outnumber her, Israel is imagined by the Left to be an almighty oppressor and is therefore seen as its natural enemy (see Améry 2005a: 137f). Améry does not euphemise the suffering of the Palestinians but stresses Israel’s fight is for survival and a ‘safe bunker for the Jews outside of Israel’ (Améry 2005b: 147). The Jews from the Arab countries would long have been ‘tragically drowned’ if it was not for the Jewish State they escaped to in the late 1940s and early 1950s (Améry 2005b: 147). And yet, the Left today does not mobilise when it comes to actual crimes against humanity in Syria, Iraq or Iran, but when the Israeli army strikes back against rockets from Gaza, the Left-led demonstrations are huge.

Left-wing antisemitism pained Améry: ‘How did it come about that Marxist-dialectical thinking gives itself away to prepare the genocide of tomorrow?’ (Améry 2005b: 142) He tried to find answers. He thought there was a ‘generation problem’ (Améry 2005b: 143). The New Left was young not only on a theoretical field but also as people. Most had not witnessed the Nazi-past. Therefore, argued Améry, they failed to see what was specific to National Socialism: eliminationist antisemitism (see Améry 2005b: 143). Instead, the New Left falsely subsumed National Socialism under the heading of fascism and ignored the eliminatory antisemitism. In short, the vast majority of the Left does not make the Shoah, the irrational extermination of Jews, a point of reference for their social theory. They do not see the inherent threat of death carried by antisemitism and its differences to racism and other forms of group-related enmity. They view Israel as an aggressor against the Palestinian Arabs and they declare solidarity with the allegedly weak against the strong. Antisemitism in the shape of anti-Zionism becomes acceptable, or in Améry’s words ‘honorable’.

In a talk given in 1976 at the Brotherhoodweek, an interfaith event of the Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation, Améry called for the Left to rethink its stance towards Israel (see Améry 2005e: 191). Since then, the problem of antisemitism on parts of the Left, internationally, has only worsened, especially since alliances have been formed with traditional right-wing and Islamic antisemitism. Améry’s demand is more pressing today than ever.

The categorical imperative after Auschwitz

Améry brings to mind what it means to translate Theodor W. Adorno’s categorical imperative – ‘Mankind has to arrange their thoughts and actions so that Auschwitz will not repeat itself, so that nothing similar will happen’ – into concrete terms (Adorno 2003: 358). The Shoah is the brutal manifestation of a society in which we can trust neither reason nor the self-preservation drive of perpetrators. Eliminationist antisemitism constituted the core of Nazi ideology, which is why even when the tide of the Second World War turned against Germany, it remained the regime’s priority. The mania went so far that even when the war was foreseeably lost, the killing of Jews did not stop until the total defeat of the Germans. The Nazis were willing to sacrifice themselves in order to eliminate what they saw as ‘world Judaism’. In contrast to other horrible and cruel genocides, the Shoah is unprecedented because of this absence of instrumental reason. That is why a new categorical imperative after Auschwitz is required. Kant’s and at a later date Marx’s categorical imperative are no longer sufficient. Today, we also need Adorno’s.

History has shown that Jews cannot rely on others to come to their rescue and that the existence of a Jewish State is essential to prevent a new Shoah. Because of this, Israel differs from every other state in the world. Today, believed Jean Améry, ‘Who questions Israel’s right to exist is either too stupid to see that he engages in the realisation of a new Auschwitz or he consciously aims at this new Auschwitz.’ (Améry 2005c: 158)

Bibliography

Jean Améry, At the Mind’s Limits. Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities, Bloomington 1980 (1966).

Jean Améry, Der ehrbare Antisemitismus, Werke Bd. 7. Stephan Steiner, Stuttgart 2005a (1969). Translation M.G.

Jean Améry, Die Linke und der ‘Zionismus’, Werke Bd. 7. Stephan Steiner, Stuttgart 2005b (1969). Translation M.G.

Jean Améry, Juden, Linke – linke Juden, Ein politisches Problem ändert seine Konturen, Werke Bd. 7. Stephan Steiner. Stuttgart 2005c (1973). Translation M.G.

Jean Améry, Der neue Antisemitismus, Werke Bd. 7. Stephan Steiner, Stuttgart 2005d (1976). Translation M.G.

Jean Améry, Der ehrbare Antisemitismus: Rede zur Woche der Brüderlichkeit, Werke Bd. 7. Stephan Steiner, Stuttgart 2005e (1976).

Jean Améry, Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne, Werke Bd. 2. Gerhard Scheit, Stuttgart 2002 (1976). Translation M.G.

Theodor W Adorno, Negative Dialektik, Gesammelte Schriften Bd. 6. Rolf Tiedemann. Frankfurt am Main 2003 (1966). Translation M.G.

Comments are closed.