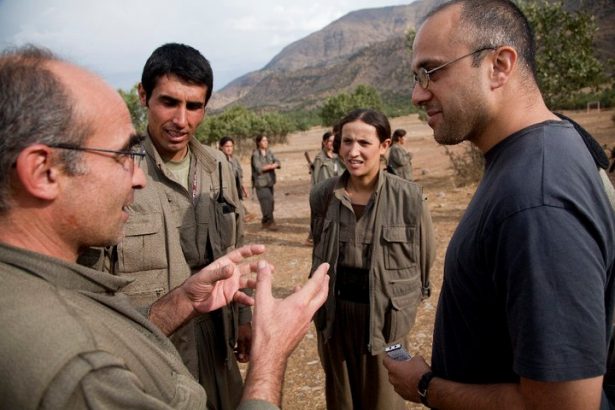

The Fathom editors hold a monthly invite-only round table discussion in our London office between a policy expert and a group of opinion-formers. In May, Jonathan Spyer, director of the Rubin Center for Research in International Affairs, a centre located at the Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya (IDC) – and one of the few policy experts to regularly visit the front lines and talk to the warring factions – mapped the current state of the Syrian conflict and its implications for Israel.

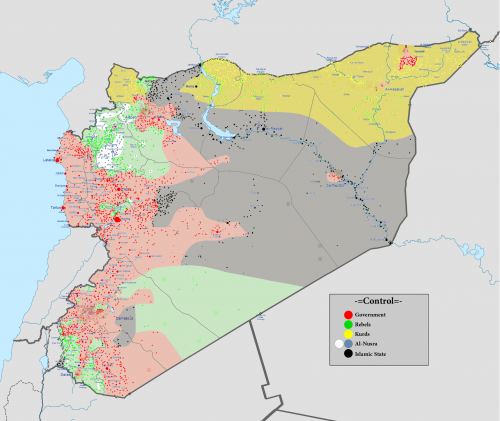

Syria has been a divided country since the summer of 2012. There are four actors, each with a sphere in which they hold power – the Assad regime, the Sunni-Arab rebellion, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), and Syrian Democratic Union Party (PYD). The Syrian civil war has become a fusion of seven entwined conflicts. First, the conflict that gave birth to all the others, between the Assad regime and the Sunni-Arab rebels; second, the conflict between the regime and ISIS in central Syria; third, the rebels against ISIS in north-west Syria; fourth, the Kurds against ISIS in northern Raqqa province; fifth, the Kurds against Assad in northern Syria; sixth, the Kurds versus the Sunni-Arab rebels in the north-western part of the country at the isolated Afrin enclave; and seven, Sunni-Arab rebels against Sunni-Arab rebels, specifically in the area east of Damascus between two rebel groups: Liwa al-Islam and Fariq al-Rahman. Lastly, I will ask what all of this means for Israel, and how Israel proposes to defend itself.

Syria’s Fragmentation

The road to fragmentation took its first major turn in the summer of 2012 when the Assad regime unilaterally withdrew from a large section of the north and east of the country. It was a significant decision because it revealed the schism between the rhetoric of the Assad regime – ‘the sole legitimate government of Syria’ and so on – and the reality on the ground – he had a shortage of manpower. Thereafter, Syria divided into three areas: the Assad regime area, consisting of the capital of Damascus, the coastal area and Aleppo; three enclaves controlled by the Kurds, who later united two of the enclaves; and the remaining area controlled by the largely Sunni-Arab rebellion. This rebel controlled area was sub-divided again in the course of 2013 and 2014 with the arrival of new militias from Iraq, including the al-Qaeda branch of Iraq, rebranded as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which drove out other rebels in the eastern Raqqa and Deir az-Zour provinces and established its exclusive rule, and then embarked on territorial expansion further inland.

The map has remained more or the less the same since mid-2012 with some subsequent variations. Over this period 300,000 people have lost their lives either fighting or being victim to the fighting, but the dynamic of the war has stayed the same: a division into separate enclaves, largely defined by sectarianism.

The Assad regime has benefited from two salient factors which have ensured its survival. First, it has found very reliable and supportive allies in Russia and the Islamic Republic of Iran. The Russian contribution evolved from diplomatic cover and the supply of weaponry to direct military assistance after 30 September 2015, when President Vladimir Putin directed his air force to begin bombing opposition areas. The Iranian role has been the vital provision of manpower. And second, Assad has benefited from the relative cohesion and loyalty of the absolute inner circle of his regime. As a result of these factors, Assad’s rule is not under threat, but he’s not strong to reverse the situation back to the status quo antebellum.

Regarding the Sunni-Arab rebellion, its greatest drawback has been the absence of unity – the inability to develop a single, authoritative political leadership to control the military forces on the ground. This is quite an astonishing thing if we think about it – for the first four years of the civil war we have been unable to identify a single figure or political movement we could agree was the leadership of this rebellion. Yet, for all their drawbacks, the Sunni-Arab rebellion have nevertheless stayed in the game. Now we have an emergent contender for the leadership of the rebellion: Jaish al-Fatah (Army of Conquest), a coalition of the two most powerful Sunni-Islamist forces, Jabhat al-Nusra (al-Qaeda’s branch in Syria) and Ahrar ash-Sham (Salafi in nature but not linked to al-Qaeda). The unity of those two forces, and the number of smaller groups around them, is the force to watch right now in terms of taking on regime forces.

The Kurdish sphere, under the tutelage of the PYD, consists of two enclaves: Afrin in the north-west and Rojava in the east of Syria. These two enclaves represent a single contiguous area of Kurdish control, stretching all the way from the Iraq-Iran border to several hundred kilometres into Syria, internally divided by different Kurdish nationalities. I last visited this area four months ago and experienced a tightly governed space, able to restrain any threat to its rule (except for two regime-controlled areas in the towns Hasakah and Qamishli). There is some authoritarianism, but it is one of the most peaceful areas in Syria today. Interestingly, there is a significant gap between the PYD’s military strength and its relative political weakness. It was noticeably absent in Geneva and even its declaration of official autonomy in north-east Syria has been completely ignored by the world’s chancelleries.

The fastest growing sphere in 2014-5 was the ISIS sphere, but that is now the sphere losing the most ground. It has lost between 25 to 30 per cent of the territory it once controlled in Syria. It lost Palmyra to the regime, its last bridge along the Euphrates River to Kurdish forces, as well as large swaths of north-east Syria to the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Combined with territorial losses, ISIS has been forced to cut its fighters’ salaries, has had to cope with a decline in the number of foreign fighters entering its area, and is suffering from US air attacks on its oil infrastructure and banks. Yet, there is no sense of serious internal unrest in the areas under ISIS control. It is an extremely effective and brutal regime that controls its inhabitants with great cruelty. There are rumours of an imminent assault by Kurdish forces on ISIS-held Raqqa city; my own sense is that it’s not coming just yet, but it will come in the near future.

Israel’s Precarious Situation

Where does Israel fit in all of this? Geographically, Israel comes into this in the far south-west, behind the Golan Heights and to the west of Quneitra Governorate. In order to understand the Israeli view, we need to venture back to before the start of the Syrian uprising. In the years preceding the Arab Spring, the dominant view in Israel was that compromise with Assad is in Israel’s interest for the following reasons: Israel viewed Syria as the weakest link in the Iran-led alliance, and therefore, through the inducement of territory concessions in the Golan Heights, Assad could be drawn away from Iran, and thus the real enemy – the Iran-led alliance – would be dealt a serious blow. This narrative was one of the early casualties of the Syrian war, once it was clear that Assad had chosen – wisely in terms of his own survival – to remain within the Iran-led alliance.

Israel miscalculated about Assad’s imminent downfall in 2012. Although this analysis was wrong, it was part of a wider misjudgement of the realities on the ground. Post-2012 Israeli analysis is divided between those who think that the rebels should win because their victory would deal a greater blow to the Iranians, and those who think a victory for a weakened Assad will be better for Israel, because he is ‘the devil we know’.

There are two reasons to intervene at some level in Syria: control of the area adjacent to the Golan Heights; and the prevention of sophisticated weapon transfers to Hezbollah in Lebanon. It is clear that Israel prefers the rebels not the regime to have control east of the Golan Heights. There is a clear understanding in Israel, particularly from defence officials, that it is the intention of the Assad regime, Iran and Hezbollah, to establish the frontier of the Golan Heights as an additional line – the other being the Lebanese border – to attack Israel. There is an historical irony to this: Hafez Assad always preferred to keep the Syrian border quiet and to use South Lebanon as a place to attack Israel; now Hezbollah and Iran are returning the compliment. There is an additional problem. The group known as Yarmouk Martyrs Brigade, a franchise of ISIS, has taken control of a town on the Syrian-Jordanian border, posing a threat to Sunni-Arab rebels and Israel too.

The other threat to Israel is the transfer of weapon systems to Hezbollah. Despite large amounts of Israeli military action over the skies of Syrian to prevent such transfers, we won’t know how successful Israel has been until there is another war between Hezbollah and Israel – if we know what Hezbollah is using, then we will know how successful Israel was in preventing such transfers. Israeli diplomacy vis-à-vis Russia has been successful, ensuring that Israeli air patrols can continue unabated over Syria.

Question 1: ISIS is fighting in three of the seven conflicts you mentioned, as well as suffering heavily from US airstrikes. Do you think ISIS will still be present in Syria as a fighting force in the next year and a half?

I do not see ISIS disappearing from the Syrian battleground entirely, but I think within 2 years ISIS will lose Mosul in Iraq, and consequently, lose the largest symbol of its ‘Islamic state’. And it will continue to lose ground in Iraq and Syria, defeats which I do not see how ISIS can reverse. The main issue for the West is not military but political: what is the most suitable force to fight, and ultimately control, ISIS-held territory, which is predominately Arab? The US has found a partner in the SDF, but it is problematic as the SDF is approximately 90 per cent Kurdish. It remains to be seen whether there will be sufficient inducement to get Arab involvement in it.

Question 2: Each actor is dependent on external support. What might have happened if the US and EU had put in their resources at the beginning of the war in a similar way to Iran and Russia?

From my conversations and interviews with the people involved early on, in the uprising in Idlib, I do take seriously the notion that the initial iteration of the armed rebellion in early 2012 was not Salafi-Jihadi in nature. The Salafists were present in the beginning, but there were other, more dominant forces too. I do tend to sympathise with the view that had a larger amount of resources been put into the Syrian rebellion at its initial stages, it might have been possible to create a rebellion with a different ideological disposition. Would the rebellion have been democratic? Possibly not: it might have produced an authoritarian Sunni-Arab rule of Syria, though not necessarily a Salafi-Jihadi-Islamist one. However, by 2013 a western-led rebellion was impossible because, due to the evolving situation on the ground, it became inconceivable to dislodge the militarily better equipped Salafi-Jihadi groups.

However, some efforts have been made to aid the moderate parts of the rebellion – in 2014, the US sent serious weaponry such as anti-tank systems to selected groups in north-west Syria, such as the defunct Harakat Hazm and Syrian Revolutions Front. What happened to those organisations? A type of natural selection process materialised whereby stronger Salafi-Jihadi groups, such as Jabhat al-Nusra, turned on them. Jabhat al-Nusra is now a permanent part of the Sunni-Arab rebellion because it is far too strong for other moderate rebels to fight and dislodge it. In the northern Aleppo countryside the Turkish government is supporting a constellation of smaller, non-Jihadi groups. Yet the military evidence of recent months suggests that they will not be effective in preventing ISIS expansion. The Turkish government has failed to convince the US administration that these non-jihadi groups, instead of the Kurdish-based SDF, are the best partner on the ground to defeat ISIS. All indications are that al-Nusra is getting stronger and might declare an emirate in north-west Syria: not an ‘Islamic State’ province whereby all Islamists must pledge an allegiance, but an area of strict Islamist law under al-Nusra’s rule.

Question 3: The Kurdish leadership in Syria is in short supply of regional allies. Could you envision any scenario whereby Israeli-Kurdish political relations develop beneath the surface of the conflict?

It is very important to differentiate between the two dominant Kurdish forces in the region: the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) of Iraqi Kurdistan and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) of Turkey. Israel’s relationship with the pro-business, pro-American KDP is very good. Israel’s relationship with the PKK is not so good – mainly due to a more complex history. Kurdish attitudes towards the Israelis are less hostile than to the Sunni-Arab rebels or the Assad regime. If the Syrian Kurds are able to balance their political relevance with their military relevance there is considerable potential for communication with Israel.

Question 4: Are the Turks willing to get more aggressive in stopping the Kurdish advance in northern Syria?

The Turkish leadership has declared that Kurdish expansion into the 60km area along the Syrian-Turkish border between Jarabulus and Mregel, which is currently controlled by ISIS, is a clear red line for them. The Kurds are torn between their main goal of connecting the two Kurdish enclaves, which would result in crossing this read line, and the US’s goal of wanting the Kurds to attack ISIS-held Raqqa. The Turks would like to see the defeat of ISIS, but they absolute oppose Kurds controlling the entire Syrian-Turkish border. There is no mandate for an intervention by Turkey beyond that: Turkish parents do not want to see their children return in boxes for no apparent reason; the army does not want to get involved; and Turkish President Recep Erdogan is smart enough not to allow the Republican People’s Party (CHP) to regain any political capital it lost in the last general election.

Question 5: The Israelis have been playing cat and mouse with different political groups in Syrian is because its main concern is the fear of Iran. I think in the long-term Israel has more long-term interests with the Shi’a world than with the Sunni world. Do you think the Israeli government needs to change its approach?

First of all, to say Israel is behind certain forces is simply inaccurate. What Israel is doing is staying out. You do not find footprints of Israel in Lebanese or in Syrian oppositional politics. What’s happening in Israel, for better or for worse, is the institutional horror of interfering in political processes across its borders. Israel sometimes misses opportunities because of this.

The point you make about a ‘Shi’a versus Sunni’ conflict is very interesting. As far as the Israeli military establishment sees it, the most powerful forces actively trying to harm Israel emerge from the Shi’a-led regional bloc. There is nothing comparable to the physical threat of those forces to Israel on the Sunni side. Could that change in the future? Absolutely. Israeli security officials would be derelict in their duty if they were not looking very closely at the Sunni terrorist rebels in Syria, and also at the growth of ISIS in the Sinai and the Gaza Strip.

Although Israel’s focus on the Iran-led alliance is rational, it can over-blow the extent of the Iranian threat. If we look at the political map of the region, what we find is that the Iranians aren’t actually capable of building long term alliances and relationships with anybody other than Shi’a or minority forces. As a result, in all the areas which they are engaged – Yemen, Iraq, Syria – the net result of their engagement is not Iranian hegemony but continued conflict and chaos, in which Iranians have to invest considerable political and military capital to keep its proxy in the fight. Iran is therefore a less potent threat than it likes to present itself as.

Question 6: How does Hezbollah’s involvement in Syria impact on the threat they pose to Israel?

If the Syrian war continues for a long time, then I expect that Hezbollah will have no desire to open up another front against Israel – it’s just not conceivable. Hezbollah has invested a considerable amount of its military infrastructure in the Syrian war, is forced to recruit younger and younger soldiers, and are reportedly giving financial inducements to poorer families to force their sons to sign up. There are even indications that Hezbollah has begun recruiting non-Shi’a. They do not have the serious political and ideological indoctrination that we are accustomed to see in Hezbollah fighters. But, when the civil war ends, Hezbollah may well emerge as a leaner, stronger, more experienced machine. They would have learnt new skills; how to fight in unknown terrain and how to fight in urban areas – a skill which Hezbollah has never had cause to develop in the past.

If we look at the level of Hezbollah responses to what are apparent Israeli killings of senior Hezbollah personnel, we can deduce that Hezbollah does not want to push Israel. If you kill Hezbollah military chief Imad Mughniyeh (and an Iranian general at the same time) and the response from Hezbollah is to fire an anti-tank missile at a jeep in Shebaa Farms, well, that’s not really much of a retaliation. I would even go as far to say that Hezbollah’s hasty investigation into the killing of Mustafa Badreddine, which concluded within 24 hours of his death that there was absolutely no Israel’s involvement, sounded like a case of, ‘No, no, no, Israel was not involved in this. There is no need for us to retaliate.’

Question 7: How will extremist rebels groups such as Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS react when they start to lose territory and ground? Will they return to a more routine terrorist modus operandi?

I think that’s most likely. Take, for example, ISIS. As I noted earlier, over the past few months ISIS has been losing ground to the regime and to Kurdish forces. Then 150 people were killed in several explosions in Jableh and Tartus, towns deep in the heart of what the regime think is their safe enclave. I think the balance of probability is that these attacks were carried out by ISIS. In 2014, when ISIS declared its Caliphate, the number of terrorist attacks was minimal. In 2015, when ISIS started to contract in geographical size, we noticed a rise in its terrorist activities: first in Surat, then Ankara, then the downing of the Russian plane over the Sinai, then Paris, then Brussels, and now maybe the Egyptian plane over the Mediterranean. My sense is that the state project is going to be increasingly threatened; even if it is still there, winning victories, there will be no propaganda value anymore in the state’s advancement. So what you replace that with is terrorist spectaculars in Iraq, and now in regime-controlled Syria.