Perry Anderson’s War

Editorial introduction to the Symposium: Perry Anderson’s long essay, ‘The House of Zion’, was published in the November-December 2015 issue of New Left Review, the ‘flagship journal of the Western Left’. Fathom invited Shany Mor, Cary Nelson, John Strawson, Michael Walzer, Mitchell Cohen and Einat Wilf to respond to Anderson’s essay.

Available online, and given the status of an NLR ‘Editorial’, it was the Marxist equivalent of a Papal edict. Anderson was the journal’s long-time editor, and is perhaps the most gifted intellectual historian of his time, author of Lineages of the Absolutist State, Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism, Considerations on Western Marxism, English Questions, The Origins of Postmodernity, and more. In this outing, Anderson serves as episcopus servus servorum Dei, or, the servant of the servants of God (in this case a secular God). Over 14,000 words, he excommunicates the two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and anoints an alternative: ‘the demand for one state is now the best Palestinian option available.’

Anderson’s essay is a summa of the thinking of the Left that has lost its way on the question of Israel. For one thing, his proclamation proceeds untouched by the categories with which classical Marxism has traditionally approached unresolved national questions: ‘internationalism’, ‘chauvinism’, ‘peace between nations’, ‘people’, ‘class’, ‘consistent democracy’, ‘the right to national self-determination’, ‘minority rights’, and ‘federalism’. Instead he prefers the decidedly non-Marxist categories of ‘the Arab states’, ‘their traditional enemy’, the homeland’, ‘the West’, ‘Arab turbulence’, ‘the Zionists’, ‘the Resistance’ and ‘the New World Order’.

Anderson’s dream that the ‘strategic emplacements’ of the Arab states will end the existence of Israel is a far cry from the Marxism of Lenin, who believed national self-determination and consistent democracy was the way to ‘clear the decks for the class struggle’; from the sophisticated discussions of the national question, the rights of peoples, and the mechanics of federalism of the first four congresses of the Communist Third International; and from Trotsky’s late support of the Jewish people’s right to survival as a nation and to live as a ‘compact mass’. In place of all that, conspiracism is passed off as sophisticated geopolitics, class politics is bracketed ‘for the duration’, and fascistic political forces are embraced as ‘the resistance’.

*

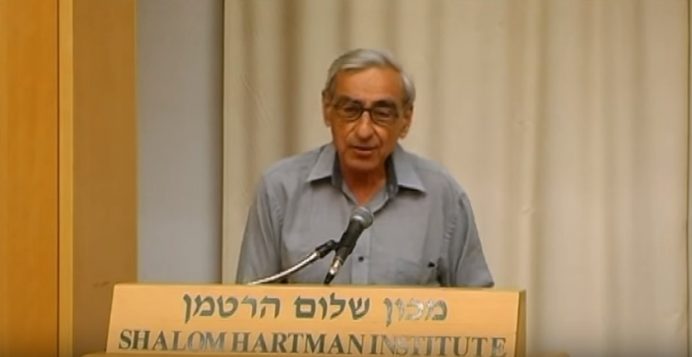

Michael Walzer is struck by Perry Anderson’s contempt. Contempt for any Palestinian politician who isn’t actively engaged in ‘resistance’, contempt for all those who hope for mutual accommodation between Jews and Palestinians, who are ready to accept a state alongside Israel and to call that the end of the conflict, who are engaged in a common struggle against terrorists and religious fanatics, and who are trying to turn the Palestinian Authority into a nascent state – these, Walzer notes, are the chief villains in Anderson’s story.

There are parts of this long essay with which I entirely agree, but its steady political thrust and what I will call its persistent undertone are radically disagreeable. I was reminded reading it of an old New Yorker cartoon: two old men are sitting in their club, drinks in hand, and one of them, leaning forward in his chair, says to the other: ‘I say it’s war, Throckmorton, and I say, Let’s fight!’ I am sure that Perry Anderson doesn’t sit in a club like the one portrayed in the New Yorker, but he is definitely eager to fight – or eager for the Palestinians to fight. Whether he favours a purely political or also a military fight, violence or non-violence, is unclear. He doesn’t talk about terrorism at all, though he hints at the usual apologetic account of it (‘an explosion of frustration and despair’). His last paragraph seems to call for Arab states to threaten war against Israel (once they are in full control of their ‘strategic emplacements’). But his militancy is non-specific.

What is certain is that he has nothing but contempt for any Palestinian politician who isn’t actively engaged in ‘resistance.’ All those who hope for mutual accommodation between Jews and Palestinians, who are ready to accept a state alongside Israel and to call that the end of the conflict, who are engaged in a common struggle against terrorists and religious fanatics, who are trying to turn the Palestinian Authority into a nascent state – these are the chief villains in Anderson’s story. The sentences about them are one long angry sneer: they are ‘compliant notables,’ ‘placemen,’ ‘cost-effective surrogates for the IDF’ bloated with ‘the proceeds of collaboration.’ They work ‘hand-in-hand with the Shin Bet to hold down popular unrest on the West Bank.’ They run ‘a parasitic miniature of a rentier state’ and they aspire to be the ‘tin-pot ruler[s] of a Transkei by the Mediterranean.’ Anderson is superior to all this. He says its war, and he wants them to fight.

Actually, they have fought – in 1947 and 1948 against the original two-state solution (the UN partition plan), and many times since with terrorist attacks against Israeli civilians, and once, briefly, with a mass uprising, not quite non-violent but disciplined and participatory. Long ago, Leon Trotsky wrote that ‘terrorists want to make the people happy without the participation of the people,’ and this is a useful critique of Palestinian terrorists (and of many others, too). But it isn’t a useful critique of the First Intifada, which was a popular engagement – and the only successful example of Palestinian political action. It led to the Oslo Accords, of which Anderson, of course, is contemptuous. Oslo is yet another example of what he calls the ‘ruinous leadership’ of the Palestinian national movement. It would only have produced that ‘Transkei by the Mediterranean.’

But, given the ruinous leadership – and I haven’t mentioned Palestinian authoritarianism, brutality, and corruption, which Anderson mostly gets right – what hope is there for any decent outcome? The situation is made even more hopeless by the character of the ‘surrounding Arab landscape … its suffocating universe of feudal autocracy and military tyranny, client regimes, and rentier states.’ Nothing will change, Anderson writes, ‘without a revolutionary transformation.’

Well, we always knew that. After the Revolution, everything will be better, indeed, absolutely better. Jews and Arabs will live in peace in one state (if there still are such things as states) and the lion will lie down with the lamb. But the Revolution, like the Messiah, isn’t immediately on the horizon. What to do until the Coming?

Anderson would like the Palestinian leaders to give up on Transkei and begin (even though it’s hopeless) a campaign for citizenship and the franchise in a single state between the Sea and the River. But this democratic solution has one odd problem: it isn’t the aspiration of the demos. ‘Neither Jews nor Palestinians have the slightest wish for it,’ says Anderson, though he immediately adds that this is more true of the Jews than of the Palestinians ‘for whom abandonment of the hope of a separate state for integration into [Greater] Israel could become preferable to indefinite asphyxiation in the status quo.’ Note the verb form, ‘could become,’ which means hasn’t yet become. For the time being, pending revolutionary and other transformations, both the Jews and the Palestinians want a state of their own. Together, they want two states.

Anderson thinks that any Palestinian state alongside Israel will be a puppet state, politically collaborationist, an economic satellite. And that, indeed, is what those Israeli right-wingers who haven’t adopted the settler one-state solution want; that’s the only Palestine they would be willing to recognise. But we can imagine their political defeat; the rule of Netanyahu and his friends is subject to democratic rejection. This would indeed be a major upheaval in Israeli politics; it wouldn’t, however, be a revolutionary transformation. I am confident that Israeli nationalists and religious zealots will be defeated before the coming of the Messiah (they had better be since I can’t promise that the Messiah won’t be a religious zealot – just as Anderson can’t promise that the Revolution will bring democracy and socialism to the Arab world).

We should never underestimate the value of sovereignty. People whose lives and well-being are protected by sovereign states should be especially leery of telling stateless men and women that they shouldn’t aspire to a state of their own. Once there is a sovereign Palestine, the Palestinians will be better off – immediately better off because they will have, within whatever constraints, the power of self-determination. And given the educational level and entrepreneurial talent of the Palestinian people and the readiness of some European states and maybe some Gulf states to invest in a Palestinian economy, they would have the prospect of steady material advance. There wouldn’t be equality between Palestine and Israel (ruinous leadership does have consequences) – except in the formal sense, not entirely unimportant, in which Israel is equal to, say, Italy or France. But there would be much greater equality than exists now, under the occupation. It would be a significant step up, and why would anyone, why would any leftist, want to deny that step to the people of Palestine?

Comments are closed.