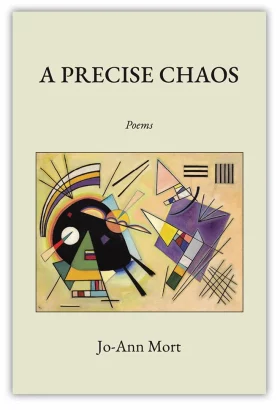

Jo-Ann Mort has been writing about the Middle East conflict for decades, maintaining the kind of relationships on both sides that few people can claim. And now there is her debut poetry collection, A Precise Chaos, recently published by Arrowsmith Press. Reading it at a moment when the shaky ceasefire between Israel and Gaza creates continued fear for the future, Mort’s collection offers a necessary witness to years of violence, loss, and love. Her poems all carry a profound sense of searching, a permanent undercurrent of unrest and disconnect.

Jo-Ann Mort brings vast experience, and travels, to her poetry. From Africa and Eastern Europe to the Middle East and major world capitals, she probes beneath surfaces and behind scenes, bringing this same scrutiny to the US, where she lives. Her essays and articles for international publications cut through polarised opinions and political obstinance with rare levelheadedness. This intimate knowledge of multiple worlds permeates Mort’s work, making her not an indifferent bystander recording events, but an enduring witness with a past of her own.

‘I am alone in a vast continent,’ she writes in one of her poems and it is this line that particularly strikes me. It sums up the enormity of conflict, and how Mort posits herself within this space. She lingers over people and places, she zooms in on the nitty-gritty details so often overlooked, until they become the details that matter.

There is that time in the evening, always

When the toasts are finished and the light touch

On the knee, friend to friend, snaps apart

Like the broken head of a doll

In each of her poems, such as this one, ‘Nighttime in Jericho’, Mort herself is present, both a concerned witness and a wry commentator. In a crowd of people, she is alone. This is also true of ‘Uncoupled’, a poem which appears toward the end of the collection, in which she uses the biblical story of Noah’s Ark as a vehicle to talk both about conflict areas and herself, all at once:

It rained for 40 days and 40 nights.

The couples walked up the plank

to the ark. I stood outside, uncertain

how to ascend; uncoupled, unhooked,

a lone woman, my feet soaked from

the sagging earth.

The sagging earth is the world in which we live, crumbling under the weight of the worries of the world. Perhaps this is a call for a restart, a way to salvage everything that has been broken, everything Mort has seen with her own eyes over the years. There is a sense of urgency here as the waters rise, as she continues into the second stanza:

The waters surged above the sidewalk.

My body half-immersed in the storm

water, like a warm, but dirty bath.

No one grabbed my hand. No one

embraced me as the waters rose.

Then, I saw the horizon ripple through the waves.

There is sadness here in these spare lines, but there is also hope in the horizon as it shimmers through the waters. When I read this poem I instantly think of the ongoing Palestinian-Israeli conflict, particularly the last two years of killing and destruction, the immense suffering and pain on both sides. I think of the stress that has been placed both on Palestinian and Israeli society; this poem gives me a glimmer of hope, a faint ripple on the horizon.

Mort uses concrete imagery to illuminate political realities. In ‘On the Day After Christmas’ there is palpable claustrophobia, and a chilling image of how holiness and violence occupy the same cramped space.

So that this jeep was almost like a tank,

a difficult dancer on the hills that barely stretch

from Jerusalem to this birth city, a literal stone’s throw

popping from one holy name to the next,

Jerusalem-Bethlehem-Bethlehem-Jerusalem.

All this is circumvented by Israel’s barrier, ‘the gray cement wall snaking and standing.’ Mort has spent time on both sides of this wall; her pain as she writes about it is evident. Anyone who has ever waited at the Bethlehem checkpoint, or any checkpoint for that matter, will recognise this.

There are several other poets who have written over the past couple of years about the Middle East conflict. Nasser Rabah, in his own debut poetry collection, The Poem Said Its Piece, writes searing witness poems from Gaza, co-translated by Ammiel Alcalay, Emna Zgal, and Khaled al-Hilli. Yonatan Berg, whose poetry I have had the pleasure to translate, has written extensively from his own unique Israeli perspective, looking back on his past with sorrow and exploring reconciliation and the possibility of peace in today’s broken world. American psychiatrist and poet Owen Lewis’s recent collection, A Prayer of Six Wings, addresses the aftermath of 7 October and examines Jewish grief while striving for shared grief across borders. Each writes from within their own experience – Rabah from Gaza, Berg from Israel, Lewis from his experiences following 7 October. Each poet offers a unique perspective. Mort, who has spent decades witnessing both Israeli and Palestinian realities from close up, writes from the space between.

Yet the collection is also deeply personal, a retrospective of both her life and the lives of others in a rapidly changing world. Simultaneously, it is a looking forward to what might be in the future through Mort’s own eyes.

Alongside this, the pull towards her own ancestors, her own heritage, threads through this collection. In ‘Travelog,’ for example, she subtly slips in these words in an otherwise descriptive poem about Warsaw: ‘My ancestors lived somewhere in this country / when it was Poland and when it was Ukraine.’ And in a seamless flow, she admits in the poem that follows: ‘No matter how long I search / I will never find them, the ancestors’.

She does, however, search for them and this search is distilled into many of her poems, rendering them distinctly personal. Mort is economical in her use of words and she is honest, often brutally, when talking about herself. This personal dimension enriches her political poetry, grounding observations about conflict in lived experience and inherited memory.

A Precise Chaos is a vital addition to contemporary poetry about Israel-Palestine, offering neither easy answers nor partisan certainty, but rather the witness of someone who has earned the right to write about this landscape through years of careful attention and genuine relationships on both sides of an untenable divide.