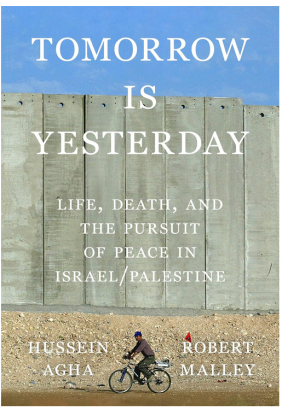

Hussein Agha and Robert Malley’s book, Tomorrow is Yesterday: Life, Death, and the Pursuit of Peace in Israel/Palestine is the story of how the 13 September 1993 ceremony at the White House lawn that enshrined the Oslo Accords developed into the 7 October 2023 atrocities and the Gaza War. Throughout these years, Hussein was my friend as well as a highly respected strategic partner in a common struggle in the search for an Israel-Palestine two-state agreement. Together and separately we witnessed the same developments, although from very different vantage points.

Whereas Agha and Malley tell us the Palestinian perception of events and narrative, I read the book through my own lens and narrative as an Israeli who was intimately involved behind the scenes in many of the events described. In order to seek a way forward, I believe both narratives need to be told and understood.

In one of the early chapters, Ghosts and Golems, Agha and Malley make several well-founded statements:

- Neither side perceived the two-state solution as their preferred outcome of the conflict;

- It took the Palestinian national movement from 1967-1988 – almost twenty years – to seek a two state agreement, a decision for which Arafat was the driving force, seeking as he did Palestinian independence and national unity;

- The Oslo agreement was in itself a great achievement, and the years that followed were a short period of relative congruence of Israeli and Palestinian aspirations;

- Yet Oslo did not keep its promise for either side: it did not lead to the establishment of a sovereign State of Palestine nor security for Israelis;

At the same time, their fifth statement – that the Israeli-Palestinian relationship during the Oslo years should be understood as a relationship between prisoners and prisoner guards – I believe to be highly unfair.

How the Oslo Years Shaped Understandings that should be Useful for the Future

For Agha and Malley, the Oslo agreement was both ‘a great achievement’ for the Palestinians as well as a ‘deceit’ although in many ways this is true for both sides. The PLO leadership and others returned from the diaspora to the Palestinian homeland; they established the Palestinian Authority; and gained wide international support they lacked before. Israel paved for itself the way to peace with Jordan; upgraded its strategic cooperation with the United States; intensified cooperation with most Arab States, as well as with Russia, India and China; and created a close working relationship with the European Union and most of its member states. All this allowed for economic growth and investment, necessary to integrate over one million Russian immigrants who had come to Israel at the beginning of the 1990s.

Yet there was also ‘deceit’. The Palestinians were promised prosperity and the likelihood of obtaining a state. Instead, income decreased due to enforced degrading security measures; continued settlement expansion took land away; and the promise of statehood remained evasive. The Israelis were promised security and stability and had to experience rising terror, internal deadly friction and the assassination of Rabin.

Why did Oslo’s promise to reach a Permanent Agreement fail? Agha and Malley offer a detailed answer (page 45):

‘As detailed as they were on interim steps, the accords were silent on matters that mattered most—Jerusalem, refugees, the ultimate scope of Palestinian territory. They did not touch on settlement growth during the interim period, even though it would have huge implications both on Palestinian lives in the present and on the expanse of land over which Palestinians could lay claim in the future. They said nothing of the Palestinians’ right to self-determination, which remained the Palestinians’ aspiration’.

From my perspective, while it’s true that issues such as Jerusalem and refugees were deferred to the second phase, the agreement – which was based on the blue-print of the Camp David Accords of 1978 – did offer a pathway to a two-state solution. Moreover, the dialogue we pursued at the time made it evident to our Palestinian counterparts what the ultimate scope of Palestinian territory would be. For example, my diary entry of May 6, 1995, reporting on a meeting in Amman of April 26, reads:

We saw Assad (Abdel Rahman, who heads the Shuman Foundation and is responsible in the PLO for the refugee file). First, we were in his office, then he took us for lunch to his home. He made a point to say that he had not bought the house, as his stay in Jordan was not permanent. He told us, he had seen a week earlier his ‘old friend’ George Habash, and he had had a long talk with Hanan Ashrawi, Faisal and Haidar Abdel Shafi. Even Haidar had been convinced by them and by the ongoing events that the present government in Israel was prepared to give the Palestinians almost 95 % of a ‘soft sovereignty’ Palestinian state – and only the Palestinian terror prevented this from happening. Assad repeated a similar statement in front of us to a member of the British F.O.[1]

With small improvements, all Israeli two state proposals were fully in line with what the Palestinian leadership understood during the Oslo years would be the territorial scope of the Permanent Status Agreement. It was also completely evident that ‘soft sovereignty’ was an essential Israeli condition. However, after the incident of November 1994, when Arafat’s forces killed Hamas fighters, the aim of Palestinian ‘national unity’ gave Hamas a free hand for increasingly devastating terror. Again here is the issue of cause and effect that has to be addressed.

Failures of leadership: The blame game over the failure of Camp David and the Clinton Parameters

In their chapter Hope and Betrayal, Agha and Malley describe the Clinton-Barak-Arafat negotiations of 1999-2001 and discuss whether Arafat should be blamed for the rejection of the Clinton-Barak offer. They bring a long and detailed description of Barak’s approach to Arafat, his negotiation techniques, and Clinton’s full support for the Israeli side, making it evident that Arafat was put in a no-win situation from the very beginning.

I too am deeply critical of Barak’s negotiations. Indeed, in May 2000, Agha, Ahmed Khalidi, Ron Pundak and I experienced a foreboding of the unfolding disaster. We were working together in the Herzliya villa of a British millionaire and watching on TV Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from Lebanon. The faces of Agha and Khalidi turned green and yellow and they told us in great pain that this event would cause immense pressure on Arafat to renew the ‘resistance’, i.e. violent action.[2]

Discussing the substance of negotiations, before the Camp David Summit, Abu Mazen told Agha that what was on the table ‘was not serious’, a statement that was fatal, and predicted the Palestinian rejection of whatever would be proposed.

Yet a fairer account of events should add two decisive facts: by signing the Oslo Accords – both the Declaration of Principles and even more so the Oslo II Agreement – Arafat accepted a wording that made it evident that the West Bank and Gaza remained ‘disputed territory’. The decisive Article was Article XI/2, which read: ‘The two sides agree that West Bank and Gaza Strip territory, except for issues that will be negotiated in the permanent status negotiations, will come under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Council.’[3]

The real problem was that if it were to accept the Israeli proposal for a two state solution, the Palestinian leadership would have been attacked and lose political capital. But were it to reject it, the leadership would be welcomed triumphantly by their people.

In the Chapter ‘Figures in a Landscape’, Agha and Malley describe this (page 67):

‘…he could lead his people only by always being in tune with them… He was among the most democratic of undemocratic leaders. There was no decision-making, no grand strategy, not even a rudimentary plan… When he turned down what was dangled before him and chose to resume the life of the rebel, he felt at one with his people, and they reciprocated in kind. He had nothing to show other than his rejection, but for a public that had lived in fear of surrender, that was plenty. The fighter had come home empty-handed. What a triumph that was.’

At the same time, despite their criticism of Barak the authors believe he honestly wanted an agreement even though the strategy he pursued was wrong.

I would be less generous to and less forgiving of both Arafat and Barak and argue that Barak was neither in tune with his own people, nor Arafat the needs of the Palestinian people. In hindsight, we all had to pay a tremendously high price for the mistakes of our leaders, something even more true after October 7 and the Gaza War.

To me Arafat’s mistakes were all vast and self-serving. On paper he created three constitutional structures – for the PLO, Fatah, and the Palestine Authority – all with detailed executive and legislative institutions and functions. In reality he did everything in his power to empty each one of any power and content. His closest co-fighters and administrators were never sure of their position or their powers; he might remove them any given moment, or act behind their backs, making it evident that their powers were an empty shell. Corruption was another means to control his people. The task of a state should be to build a government structure with the purpose of serving the needs of the people yet Arafat did the opposite. He undermined every genuine state-building effort. The effect was that the revolutionary identity, the right of resistance, and the search for ‘justice’, became more important than a secure, prosperous, dignified and law-abiding reality. It paved the way for Arafat to return from negotiations, having been ‘steadfast’, to become triumphantly glorified.

Future Palestinian leadership – aiming to prevent further tragedies and disasters – will have to put the well-being of the Palestinian people, their security, their dignity and prosperity, above the seemingly heroic aims of revenge and resistance. Future Israeli leadership will need to rebuild trust, prevent Palestinian renewed violence, not merely with deterrence, but by pursuing the essential needs and interests of the enemy-cum-neighbor-cum-potential strategic partner.

Barak’s mistakes meanwhile were self-defeating. His strategy was like a chess-player who forgets that his partner may play differently than expected. He failed to understand Arafat’s basic strategic approach, which was to keep both options – negotiations and violence – open. What was needed was to build trust, block Arafat’s return to violence, and seek agreement on one step after the other.

Earlier (on page 64) Agha and Malley speak of the importance of ‘framing the motives at stake’. Doing this in the future will require a dominant commitment to overcome the many threats ahead, and thinking about Israeli and Palestinian existential needs, in the wider regional, and intra-regional context. It will demand addressing and accepting the historic rights of both Israelis and Palestinians, as well as the crimes of both sides. Most importantly, it will involve ending the perpetual accusations of the other side, while taking responsibility for one’s own mistakes.

In any event, the events of 1999-2001 allow us to define lessons for a new start.

Lesson One: Less is more. Barak’s approach of ‘everything or nothing’ was a disaster (I believe ‘everything or nothing’ is a disaster in every sphere of life, public and private.)

Lesson Two: Aspiring for an ‘end of conflict’ was not achievable, and will not be achievable in the short to medium term.

Lesson Three: Arafat’s strategy (well described by Agha and Malley) of seeing no contradiction between negotiations and the use of violence, will most likely remain for some time to come. This means that any future peace-seeking strategy has to create a shared Israeli-Palestinian partnership against violence, and define the mutually enabling conditions to do so. During 1990-2000, we developed such concepts, a code of conduct: ‘from the logic of war to the logic of peace’ and a variety of supportive state-building, security, and people-to-people steps. This approach will have to be reinvented and adapted to changing conditions.

The Northern Ireland experience of peace-making might help. It had four important components. Both sides committed to cooperate without first agreeing on the endgame; intense and comprehensive People-to-People activities created shared bonds, networks and essential trust in a better future; third party involvement in the peace-making effort from Great Britain, the Republic of Ireland and the United States offered support (unlike the experience in the Middle East); and most important, the former enemies joined action in an effective struggle against violence.

Could a peace agreement have been signed in the years following the failures of Barak and Arafat? In their chapter ‘Decline and Fall’, Agha and Malley describe how Sharon (2001-2006) was gradually moving to accept and offer a two state agreement; and how ‘in almost every respect [Olmert’s 2008 proposal to Abbas] moved closer to the Palestinians, than what had been discussed at Camp David and Taba’. (pp 84-85). On pages 87-88, Agha describes Israeli-Palestinian backchannel negotiations, between himself and Netanyahu’s closest aide, Yizchak Molcho, with the participation of Michael Herzog and Dennis Ross. It was concluded by written understandings providing for

‘Two states, borders based on 1967 lines, with mutually agreed upon, equivalent land swaps; Jerusalem the capital of two states, Palestine would be non-militarized; Palestinian refugees provided with compensation, acknowledgement of their suffering, and assistance in finding new permanent homes.’ (p. 88).

Having spent many hours with Netanyahu, Agha felt Netanyahu wanted a two state agreement. He writes that allowing Molcho to put these understandings in writing meant that Netanyahu was willing to take a great risk in order to achieve a historic breakthrough.

Agha and Malley believe that Arafat and Abbas were too weak to follow-up constructively on any Israeli offer; Abbas was strong enough to oppose violence – gaining Israeli and international interest for him to remain in power – as long as he would say a ‘diplomatic no’ to every suggestion. He verbally accepted the Roadmap to Peace, but opposed Phase Two, which would have established a Palestinian State in Provisional Borders that would then engage state to state negotiations with Israel. He said no to Olmert’s offer and when asked was not willing to propose changes that Olmert was willing to consider. Abbas also rejected Condoleezza Rice’s request to acknowledge the Olmert offer and legitimise discussions on it. [4] Abbas also opposed implementing the many understandings concluded in twelve committees which included discussions on: water, economic relations, culture of peace, state-to-state relations, tourism, and others.[5] It did not matter that the understandings offered and concluded would have most dramatically improved the Palestinian government’s capacity to care for its citizens. And Abbas said no to the Netanyahu agreed Molcho-Agha Framework.

Several Palestinians, some of them holding very senior positions, would tell me: ‘We do not want a Palestinian State’. When asked why, they said that ‘when there will be a Palestinian State, you Israelis will be on the top of the world, and everybody will give us shit! Instead, we will negotiate, never reach an agreement, we Palestinians will be on top of the world, and you Israelis will start to fight one with another.’ I personally do not think this was the strategy Abbas pursued. The truth was simpler: He was too weak to overcome expected internal opposition. He would simply reject every proposal and every idea the Israelis would suggest. In order to keep the Americans at arm’s length, he would pretend interest in negotiating, and by continually saying ‘No’, remain in power.

Looking ahead – The problems of a two state solution

How might Israelis and Palestinians move forward? In their short chapter, ‘Yearnings’, Agha and Malley argue that Israeli and Palestinian yearnings, the hope for peace, the hope to end persecutions, threats, hate-mongering, violence and the attachment and love for the land, reach beyond the concept of a two state agreement. Israeli needs are not taken care of by a two state agreement that is followed by continuing terror and other security threats. Palestinian needs are not taken care of in a scenario in which refugees are excluded, the history of dispossession, dispersal and deprivation is not being sufficiently addressed, and attachment to the entire land is being taken away. This is to say, that concluding a two state agreement – although it would end occupation – would not necessarily bring about peace (and the opposite – Agha argues that peace might be possible without it).

As Agha and Malley write (page 127)

Over the years, the goal of negotiations imperceptibly shifted from reaching peace to achieving a two-state agreement. Those aims may sound the same, but they are not: Peace may be possible without such an agreement, just as such an agreement need not necessarily lead to peace.

It’s an important reminder that conflict existed before the occupation of 1967, and hence the issues on both sides related to 1947-48 – the Arab rejection to accept UN GA Resolution 181 followed by initiating the war, and then dispossession and dispersal; – also have to be addressed.

The role of the US and the international community

Another place I found myself in broad agreement was in Agha and Malley’s severe criticism of the policies of the US, as well as of Europe and the Arab states, and their argument that all had a major share in causing the multiple failures of the peace process. US policies are described in three phases: misreading the situation, causing failure, and then remaining oblivious to their part in the failure; and finally, lying (or make believe everything promised is just going to happen). Europe and the Arab states are blamed for ‘sanctimonious criticism of US policy and blind adherence to it.’ (pp. 178-179).

There can be little doubt that the failure of Camp David, Sharon’s unilateral withdrawal and evacuation of all settlements from Gaza (and four from the Northern West Bank), the failure of the Annapolis Process, and the waste of the 2014 framework agreement were largely caused by over-eager US intervention. Agha describes accurately the fact that Israeli and Palestinian positions harden when the United States is in the room. During the Annapolis negotiations, senior Israeli negotiator Tal Becker phoned me and told me he envied me. ‘You could negotiate in Norway without the Americans in the room, why am I not allowed to do so?’ he said.

The logical consequences of my and Agha’s feeling about undue US interference are important for the future: we Israelis and Palestinians must get at first our act together bilaterally. Having done so, we will need the essential outside support – but not before.

Yet I disagree with their claim that the ‘US shields Israel from pressure, propped up by a feckless Palestinian Authority’ (p. 181) I would argue this reverses the order of developments. The US refrained from taking effective action to overcome multiple Palestinian rejections of Israeli peace offers and rewarded Abbas for his rejections. It was President Obama, who had personal reasons to dislike Netanyahu, who decided to “punish” Netanyahu for wanting an agreement, and “reward” Abbas, for having always said “No”. In December 2016, the United States refrained from vetoing UN SC Resolution 2334.The Resolution seemingly intended to prevent settlement expansion, which in fact – it predictably did not achieve. However, Article 1 was a death blow to the Oslo Accords and Article 3 was a death-blow to any further negotiations:

Article 1 read that the UNSC

“Reaffirms that the establishment by Israel of settlements in the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967, including East Jerusalem, has no legal validity and constitutes a flagrant violation under international law and a major obstacle to the achievement of the two-State solution and a just, lasting and comprehensive peace;”

This article clearly contradicted Article XI/2 of the Oslo II Agreement, when the PLO obliged to negotiate the future of settlements and Jerusalem, while having also fully accepted Israeli jurisdiction over the settlements during the interim period. Did the UN Security Council Resolution determine that the Oslo Accords were not anymore valid? If so, why should Israel negotiate in the future, in case the United Nations would overrule agreements reached?

Article 3 meanwhile, of UN SC Resolution 2334:

“Underlines that it will not recognize any changes to the 4 June 1967 lines, including with regard to Jerusalem, other than those agreed by the parties through negotiations”

With that Article in their pocket, why should any Palestinian negotiator agree to any change of the June 4 1967 lines? Worse, should he do so, the Article legitimised massive Palestinian opposition against any possible agreement. UNSC Resolution 2334 paid of course lip service “to end all acts of violence against civilians, including acts of terror”,[6] however, in practice President Obama and his administration took a variety of actions that increased the threat of violence and terror against Israel:

Ignoring the importance of Israeli-Palestinian security cooperation, Obama’s administration recalled General Keith Dayton, who headed the United States Security Coordinator (USSC) and was achieving tremendous headway in promoting Israeli-Palestinian security cooperation; Obama dropped Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad like a hot potato, ending hereby the tremendously important state-building activity he was involved in, leaving all power in a week and corrupt Palestinian administration; forced President Mubarak of Egypt was to resign and gave the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt full support, which in turn encouraged its Palestinian arm, Hamas – then in power in Gaza – to provoke one war against Israel after the other. Even worse was that in hoping to assure a stable and secure US withdrawal from Iraq, Obama went a long way to obtain Iranian, Turkish and Hamas support, enhancing hereby growing security threats to Israel. [7]

The Palestinian Failure to Move from Revolution to State-Building

I felt somewhat personally attacked by the Agha-Malley claim that ‘Palestinians summarily dismissed Israel’s efforts to mollify them with quality-to-life promises as cynical attempts to gild their cage.’ (p. 186) – especially as Secretary of State George Shultz’s policy of ‘Quality-of-Life’ resulted from the 1980 Kreisky-Initiative which I had suggested to him, based on, and aiming to be supportive of an initiative led by the former Mayor of Hebron, Fahd Qawassme. I also had serious difficulties with their characterisation of Fayyadism ‘as a code to put good management above politics’. (p. 186) One major challenge for the Palestinians was the transition from revolutionary movement based on the ‘right of resistance’ to ‘state-builders’, based on providing security, dignity and prosperity to the Palestinian people. Regarding achieving the necessary Palestinian sea change and shift from corruption and terror to state-building, I am less pessimistic than Agha and Malley and think their criticism is far too absolute (page 198).

‘Corruption has become the Palestinian Authority’s soul, blood to its veins and oxygen to its lungs. It is a vast employment agency with no productive capacity, belief system, or ideological infrastructure, unable to protect its people, incapable of addressing their aspirations.’

When Abbas nominated the Dr. Mohammad Mustapha Government, he told them reportedly ‘you are technocrats I deal with the politics’. As a matter of fact, most members of the Mustapha government are state-builders and capable of guiding the civil servant structure that still exists in Gaza, and in the West Bank, in a professional manner. Their participation in the reconstruction of Gaza and the West Bank will be essential.

Apocalypse

Contemplating the legacy of 7 October, Agha told David Remnick that ‘it felt like a dagger in my heart’ (p. 176) a feeling I share. Agha also adds a historic observation that often ‘the story does not end there; success generates a reaction that yields its opposite.’ (p.172) I learned this a long time ago. Prof. Jacob Talmon taught that that the ideas of Napoleon’s French Revolution brought militarily to Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria and Russia, produced totalitarian regimes in all these countries one to two hundred years later. Similarly, the mistakes we made in pursuing the Oslo process paved the way for Israel’s militant right wing, as well as for Hamas; perhaps the Smotrich-Ben Gvir (official or silent) annexation of the West Bank might well pave the way for an Israeli-Palestinian one-state structure. It is an important thought that gives us hope.

Yet I am not convinced with Agha and Malley’s main thesis that (pages 8 and 164)

Yet for all that it changed, the war was neither new, anomalous, or aberrant. Not an abnormal deviation from traditional Israeli–Palestinian dynamics but their culmination. Not the wave of the future but the past’s formidable revenge’ and Hamas’s onslaught and Israel’s war of destruction were not one-offs or historical exceptions. They were historical reenactments.

The nature and essence of the current conflict is not bilateral Israeli-Palestinian, but rather regional and intra-regional. It cannot be understood without the context of Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood masterminding hate-mongering, terrorism, war and a genocidal strategy against Israel in an effort to undermine the pro-Western Arab regimes, intending to slowly and gradually strangle Israel with a multi- component strategy of encircling Israel with a ‘ring of fire’ by proxies carrying out low-scale violence, and advancing their nuclear weapons project.

I also disagree that Israel could have reached an understanding with Hamas as Agha and Malley claim. Hamas is not just a purely Palestinian movement but an important regional player, acting within the internal Arab-Muslim divide in coalition with militant religious forces intending to weaken Arab pro-Western allies that supported the status quo. After Hamas launched its coup in Gaza in 2007, Ron Shatzberg and I met a leader of the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood. His message to us made it evident that the Muslim Brotherhood movement throughout the Middle East would do everything in their power to sustain Hamas rule over Gaza, most evidently – without having explicitly said so – with the aim to undermine the stability of President as-Sisi’s regime in Egypt as well as the Hashemite rule over Jordan. The same strategic intention was hardly covered up in a meeting Brig. General Shimon Hefez and I had with the then Turkish Vice President Numan Kurtulmus in 2016.

In light of this, the presumed option of seeking a political agreement with a united Fatah-Hamas coalition never really existed. It was no coincidence that each and every effort attempt to conclude such an agreement, failed. The other alternative, to reach an Israel-Hamas agreement did not make any sense from Israel’s point of view. That option would mean Israel supporting its potential future enemy, and weakening its regional allies.[8]

Netanyahu’s choice – attempting to exploit the divide between the Fatah controlled Palestinian Authority and Hamas and befriend Qatar, was both logical and disastrous. In the face of continued rejections by Abbas – and international acceptance of Abbas’ rejections – weakening Ramallah and appeasing Qatar and Hamas seemed to offer a perfect conflict management guarantee. In effect, it did exactly the opposite: it allowed Qatar to continue its hate campaigns against Israel, and Hamas to prepare for its onslaught.

I also don’t think that Israel’s war in Gaza is simply the continuation the series of earlier brutal Israeli actions such as in Kibiya and other places as Agha and Malley claim. Those were Israeli responses against acts of terrorism, and aimed at re-establishing Israel’s deterrence capacity. I personally strongly disagree with the way Netanyahu has directed the war in Gaza. Yet we have to understand it as part of a truly multi-front war, fought in the context of Palestinians, Arabs, Iranians, and Turks celebrating the most vicious of Hamas crimes, and, as Agha and Malley write, at a time when the destruction of Israel appeared to be a realistic option and ‘Israel appeared to be on the ropes.’ (pp. 171-172).

In their chapter Yesterday, Agha and Malley explain that the past has returned

as an old glossary: Nakba, genocide, Holocaust, pogroms, settler colonialism, Palestinians-as- Nazis, the kibbutzim attacked on that day as the Warsaw ghetto, hostility to Israel as modern-day anti-Semitism:.

The importance of this chapter is not merely by being taken back to the 1890s, to 1936-1945, and 1948. Rather it is understanding that business as usual cannot work, and the revival of total enmity in the 21st century has the potential of being more devastating than everything we have known so far. Mutual dehumanisation, stemming in part from deep-rooted existential fears, has already lowered any moral barrier, permitting any and every means to revenge past crimes, and eliminate the enemy. Nobody of us knows, what means of violence might be used in the future. We should be prepared for the worst and take pre-emptive action in opposition to violence.

Messy Conflict Resolution

Where to now? Should Netanyahu not be prevented from realising his presently announced intention to occupy all of Gaza, it is hard to believe that mutual killings will not merely go on but intensify. Violent action will tend to escalate and be accompanied with intensifying Israeli efforts to push the Palestinians out of Gaza, and possibly also from the West Bank. Increasing regional and international isolation of Israel will tend to legitimise escalating acts of violence against Israeli targets and Jewish targets abroad. An only seemingly less threatening option would follow the conclusion of a ceasefire with Hamas maintaining in partial control in Gaza. The remaining threat of renewed terror will prevent reconstruction, which in any event would demand private-public investments of over $ 120 billion. This scenario would mean the Palestinian inhabitants of Gaza continuing life in the rubbles of their former homes. The despair and lack of hope will create greater despair and violence.

The biggest challenge ahead relates to leadership. The Palestinian people have paid a terrible price for their three leaders during the last hundred years who led them from disaster to disaster. And we Israelis will have to pay for the weaknesses of Peres, Barak, Sharon and Olmert, and more for the criminal acts of Netanyahu, Smotrich and Ben Gvir.

At the end of their first chapter, ‘The Beginnings’ Agha and Malley write that

An emotional and existential clash will be truly settled not through adroit verbal gymnastics but through a more painful and honest reckoning.

I hope that the Israeli perceptions in this review will be received as an essential contribution to the ‘painful and honest reckoning’.

Like Agha, I believe that the essence is to understand that “the conflict is about people, their lives, emotion, anger, grief, attachment to the land and history” (p. 254). The only people who understand this intellectually, emotionally, socially, culturally and politically are Israelis and Palestinians – and not third parties. Therefore, planning ahead has to be bilaterally, Israelis and Palestinians together.

Unlike Agha, I have my doubts whether Israelis and Jews and Palestinians living in the diaspora understand what it means to live in the conflict area. I am most suspicious in regard to their social, cultural and political motivations. I do though understand Agha’s argument, so would qualify his suggestion for the Diaspora to play an important role in seeking a way forward – joint work together of both communities living in the diaspora, mainly with the task to fight hate-mongering propaganda, might well be useful.

The immediate challenge is to end or at least minimise human suffering and pave the way for the reconstruction of Gaza and the revival of the economy in the West Bank. Much work on this has been done. Beyond and above the necessary practical moves, an immediate process of trust building is needed. The old pattern of Palestinian accusations – today more justified than ever – and Israeli reciprocal accusations, or self-criticism, will be counter-productive. Starting from the beginning should necessitate recognising the basic yearnings of each side. Not an easy, but an essential challenge.

In order to create a new start, such a reckoning will demand several understandings: An analytical strategic thinking based on several convictions that

- ‘History’ is not necessary on one side, and awareness is needed of the two painful narratives in the search of a viable narrative for the future;

- Both Israelis and Palestinians are here to stay and the understanding of the importance of a coordinated and shared future;

- A variety of possible outcomes in line with the commitment of both nations to the entire land have to be tested;

- The renewal of the content of Arafat’s message of February 1993 that while being enemies, we are partners stresses the need to renew a strategic partnership;

- We must determinedly take action against militant opposition on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian divide, reject third party imposed straight-jackets, and take coordinated action against third party spoilers.

In seeking this new start, Agha and Malley are certainly right – it will be a messy undertaking. But as Sari Nusseibeh once told me, ‘It is up to us to turn hatred into understandings. No matter how hopelessly entrenched two parties seem, their feud can be solved through an act of human will.’

The Need to Go Back to History

I remember how in our very first meeting in August 1994 in Stockholm, Agha, Khalidi, Pundak and I discussed the beginnings of the conflict with the aim of preparing an understanding for a Permanent Status Agreement. In those conversations we spoke about the past, when long after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans, and after the disastrous Jewish revolt of 132-135 C.E, the Jewish, Palestinian and the many other communities lived relatively peacefully together in the Ottoman Empire. We concluded that almost all those many religious, ethnical communities had the ambition of nation-building, which might and should somewhere down the road of history lead to a confederative Middle East. (Hussein and I both quoted Albert Hourani and his remarks in The History of the Arabs to sustain this argument. See also Agha p. 251) I pointed out that since the end of the 15th century, the Jewish community had been given far-reaching autonomous rights under the millet-system; in the 16th century, with Ottoman support, Jewish settlement and religious leadership in Palestine/Erez Yisrael experienced an important revival. In the second half of the 19th century, Jews had become the majority population in Jerusalem. Throughout the earlier centuries Jews had to be subservient to the Muslim elite, yet relations became more amicable, much similar to Hussein’s upbringing in Beirut, when most friends of his parents were Jewish, and Hussein himself would become more versed in Jewish history, literature, philosophy and religion, than most Israelis. (page 18)

In this discussion Ahmed Khalidi referred to his great-grandfather’s exchange of letters with Theodor Herzl of 1899. Yussuf Diya al-Khalidi, serving as mayor of Jerusalem at the end of the 19th century wrote to Herzl: ‘In the name of God, let Palestine be left alone!’, although he added: ‘who could contest the rights of the Jews in Palestine? My God, historically it is your country’.

Thus, for me at the very beginning of the Oslo process, there was a willingness to recognise the historical rights and aspirations of both nations; and find a way to address this in an optimal open way. From my perspective, the Zionist movement went far to address Palestinian and the wider Arab national aspirations, all along; the Palestinians did not. Understanding that neither God nor history was only on one side, what is needed is mutual recognition and the existential need to form a sustainable strategic partnership, against all the odds.

[1] Yair Hirschfeld Diary Entry, May 6. 1995

[2] A year earlier I discussed the need for Israeli unilateral withdrawal from Lebanon with Secretary of State James Baker III. I argued that we had to end the war with Lebanon and save Israeli lives. He told me it would create disastrous consequences: one of which would be to turn Syria into a most effective spoiler of any further peace effort. I felt then that my arguments were weaker than Secretary Baker’s wisdom.

[3] See text of Israel-PLO Agreement, September 25, 1995

[4] Condoleezza Rice, No Higher Honor – A Memoir of My Years in Washington; Random House, New York, p. 723

[5] Udi Dekel and Lia Moran Gilad, The Annapolis Process – A Missed Opportunity for a Two State Solution?; INSS, Tel Aviv 2021’ pp. 75-84 offers detailed information about Olmert’s peace proposal, and all the many related issues.

[6] Article 6. Calls for immediate steps to prevent all acts of violence against civilians, including acts of terror, as well as all acts of provocation and destruction, calls for accountability in this regard, and calls for compliance with obligations under international law for the strengthening of ongoing efforts to combat terrorism, including through existing security coordination, and to clearly condemn all acts of terrorism;

[7] All of this is well described and documented in chapter 9 of Hirschfeld The Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process op.cit. pp. 193-215.

[8] I could draw on a historical parallel. 1957, the Jordanian Baath party started track two negotiations with Israeli representatives (from Mapam) with the aim to obtain Israeli support to topple King Hussein. These negotiations were ended in February 1958, when President Nasser of Egypt formed the United Arab Republic, unifying Egypt with Syria and Yemen. Then, it appeared that no Israeli support was needed to topple King Hussein, and end Hashemite rule over Jordan.