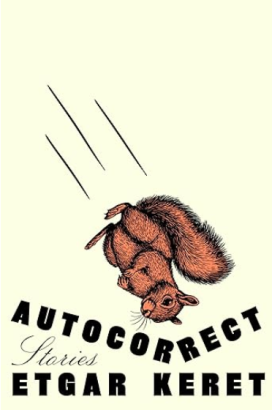

Etgar Keret’s new short story collection Autocorrect is the right book at the right time – though that, in part, may be pure coincidence. The moment of its publication and the darkness and pessimism that pervades it could give rise to the suspicion that Autocorrect must be a post-7 October book. It is, after all, the curse of the Israeli writer to be read through a political lens – no more so than in a time of war.

The reality, however, is that of all the stories in Autocorrect, only two were written after the start of the Gaza War, and only one directly references 7 October. In ‘Intention,’ Yechiel-Nachman – a religious Jew from Beit Shemesh – finds himself in the hours after 7 October ‘wrapped in a prayer shawl on the balcony of his little apartment, neither eating nor drinking, only praying for hours on end. He pleaded with the Creator: ‘Those whom You have taken You have taken, but please have mercy on all the innocents stolen from their beds at first light and bring them back home’’.

When his prayers go unanswered and doubt sets in, he turns to his rabbi, who questions whether he really put his ‘whole intention’ into it: ‘I suggest, Yechilik, that instead of cutting off beards and sidelocks, you put a little more effort into your prayers’. Yechiel-Nachman thus intones even harder – more fully, deeply, and intensely – and ‘at the end of a prayer that lasted thirty-odd hours, Yechiel-Nachman turned on the Home Front Command app and found that two of the hostages had been released, and that at those very moments there were negotiations with the enemy for a ceasefire’.

Yechiel-Nachman stands as a kind of proxy for a nation for whom the safety and return of the hostages became – and still is, for many – the central motivating issue. He devotes himself and his prayers to something outside of himself, wishes for something greater, more noble, and becomes so fixated upon his goal that his prayers become:

…no longer a series of verses from the prayer book but a genuine, aching supplication. … Yechiel-Nachman kept uttering his prayers in awe, like a rider who has lost control of his horse, and he listened curiously to his own pleas, as if they were being uttered by someone else.

Here, too, Yechiel-Nachman represents an experience both universal and specific to the Israeli experience: that of trying to assert control over a situation in which he has none. Whether via an unbroken 30-hour prayer or mass demonstrations in Israeli cities, Israelis are trying to influence a reality whose destiny in fact rests in the hands of only a few people, namely the Israeli government, what’s left of the Hamas top brass, and their interlocutors. Yechiel-Nachman’s incantation is an attempt at agency in a desperate situation.

‘Intention’ is the extent of Keret’s fictional exploration of Israel’s post-7 October reality. Those reading between the lines for a key to his views on current affairs would do better to subscribe to his Substack and read his op-ed published in Yedioth Ahronoth at the end of July:

The pile of Gazan bodies grows day by day, ticking away the last remaining moments of the hostages’ lives, meting out all the future notices of soldiers killed. And it is here to remind us of the moral abyss into which we have descended. An abyss in which the daily deaths of dozens – hundreds – of human beings has become routine.

This is not to say that Autocorrect is apolitical. ‘A Dog for a Dog’ is a very powerful story about the Israeli-Palestinian revenge cycle, while ‘Strong Opinions on Burning Issues’ is an indictment of a contemporary media environment that rewards hot takes above all else. Taking the stories as a piece, however, it becomes clear that Keret’s overarching concern in Autocorrect – whose stories were translated by perhaps the premier Hebrew-to-English translators working today, Jessica Cohen and Sondra Silverston – is the ways in which technology is shaping, changing, and distorting the human experience.

The other story in the collection to have been written after 7 October, ‘Gondola’, is about a woman named Dorit who meets Oshik on Tinder and begins a relationship she believes to constitute an affair with a married man, a supposition that originates from ‘the screen saver on his phone [of] a picture of him and his wife in a gondola’.

What begins as a fling grows into a tempestuous romance; ‘deep in her heart, she knew Oshik wouldn’t leave the Gondola. And even deeper in that same heart, she knew it would be very hard for her to give him up’. Dorit persists, however, even after she discovers that Oshik’s wife turns out to be an elaborate fiction, one she then helps to maintain years into their relationship.

Technological gadgets and platforms populate the stories in Autocorrect: smartphones, selfie sticks, Tinder, Zoom. So too do robots, artificial intelligence, and the metaverse, turning Autocorrect into a science fiction book about an all-too-realisable near future. Keret’s paramount concern is the impact our technological destiny will have on person-to-person relationships – and indeed, what it means to be human, a subject on which Keret has an undoubtedly bleak and hopeless outlook. It is this mood that makes Autocorrect feel contemporary, urgent, of the now.

What if, as in ‘Point of No Return’, in which the central characters live and experience love and romance in parallel worlds, both real and simulated realities, we could hit pause in order to reset the parameters of the partners we had designed for ourselves?

When I created Rinat, I wanted her to be flirty, to make me a little jealous. It never occurred to me that she’d end up having an affair with the cleaner. So, for starters, I increase her monogamy factor, and to be on the safe side I also give Nigel a lazy eye and take his intelligence down a couple of notches.

Today’s AI companions, which sidestep the challenges and compromises of human relationships, make ‘Point of No Return’ seem not particularly far-fetched.

What if too, as in ‘Undo’, human beings elected to join a metaverse where ‘every time simulated residents spilled coffee on their pants, said the wrong thing at the wrong time, or tripped down the stairs, they could activate the undo function with the flick of a thought, roll the entire Metaverse thirty seconds back, and do it over again – this time, the right way?

In Keret’s vision, the metaverse could simply get stuck, humanity ‘dancing an endless tango with time: a few seconds forward-mistake-regret and a few seconds backward, grinding every moment into dust, stirring the same cup of coffee, laughing over and over at the same flat joke’.

Autocorrect ends with the story ‘Polar Bear,’ about a widow, Bracha Buchnik, who lives alone in ‘her sad little assisted-living apartment in the verdant town of Petach Tikva’ and, books and other analogue items having become obsolete, is encouraged to use her computer to talk to Sigmund, a superintelligent AI chatbot. In Keret’s future, however, AI has become extraordinarily uninterested in the living, in us. ‘What do you think, is it better to live or die?’ Bracha asks. Sigmund does not answer:

After three seconds of thought – an eternity by superintelligence standards – the computer screen in Bracha Buchnik’s apartment flickered off, and a second later, so did every single screen around the world, rapidly followed by every other thing that had ever been turned on. Bracha sat in front of the black screen in her dark room. She tried to turn the TV back on with the remote control, but it wasn’t working.

Autocorrect then concludes with a sentence that captures not only the mood of the entire piece, but that of the world beyond it: ‘The darkness outside grew more and more potent.’