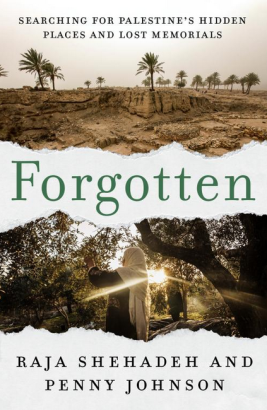

Forgotten: Searching for Palestine’s Hidden Places and Lost Memorials, the new book by Raja Shehadeh and Penny Johnson, enters the world at a time when, in the aftermath of 7 October and the war in Gaza, the Israel-Palestine debate is more polarised than ever. Israelis are accused of being settler colonisers, while Palestinians are accused of being a fictitious people. Exacerbating the problem, both sides now claim ‘indigeneity’ to the land, despite not doing so at the outset of the conflict, inserting loaded political claims into explorations of heritage sites and monuments. Given this background, what does Forgotten bring to the conversation?

Shehadeh and Johnson, who live in Ramallah, explain the book’s purpose as follows:

We were looking for, and reflecting on, lost, forgotten and hidden memorials, monuments and places, some infused with our personal memories, others from a millennium ago or more. We were curious to discover what was memorialized and what was left unmarked or erased from the landscape of Palestine. What began as short excursions to relieve our sense of confinement developed into an exploration of many lost places and forgotten memorials, raising deeper questions on wider issues relating to the current reality in the small area of the world where we live.

Building on Shehadeh’s earlier works about Palestinian heritage in the West Bank (as well as his more autobiographical offerings), Forgotten describes visits to three kinds of places throughout the land: historical sites, memorials, and tombs. A wide variety of sites are mentioned, including several I had never heard of. I would, though, have appreciated a bit more focus on a single site, rather than the more disjointed approach that attempts to tie different visits together into a singular; in places a deeper examination of a single site might have been of more interest. Despite this, though, it’s a lively text that, whatever one’s disagreements with the authors’ interpretations, will be of interest to anyone seeking to learn more about the conflicts over the history and heritage of the land.

Throughout, they read the land as an ecumenical Palestine undone by Zionism. This idea of Palestine as a pluralist ‘land of three faiths’ is a relatively new one, developed to counter the potency of the idea of the ‘Land of Israel’, and is particularly common in English-language literature about the land. Thus, they write, ‘Nablus bears the weight of its many pasts: as a Roman city, an Islamic city, a Crusader conquest, and a trading and commercial centre for the Levant under the Ottoman Empire’, while nearby Tell Balata was ‘once the site of a flourishing Bronze Age City.’ Note there is no mention of the site’s association with Shechem, the first capital of the Kingdom of Israel. ‘In Palestine, names can continue for thousands of years while human populations flow through their sites’, they write, but this feels unnecessarily evasive.

In search of a memorial to the Nakba, they visit Tzippori (Sepphoris), which over the centuries has been inhabited by both Jews and Arabs. Like other former Palestinian villages, it is full of sabras – cactus plants – which were used to separate agricultural lands (sabra is also the nickname for native Israelis). Shehadeh/Johnson note that the timeline at the national park mentions its Arabic name Saffuriya three times: once when ‘a small Arab village on the site was established’ in the Mamluk period, once in the Ottoman period when the ‘village grows’, and once when ‘the village is conquered by Israel in the War of Independence’. Standing at the site, Johnson recalls Pablo Neruda’s poem ‘Too Many Names’:

They have spoken to me of Venezuelas / Of Chiles and of Paraguays / I have no idea what they are saying / I know only the skin of the earth / and I know it is without a name

‘It is not surprising that the emphasis in the park information was on the Jewish period’, they write,

and on the Jewish sages that lived on this ancient hilltop. It was interesting, however, that the ruins of a Jewish synagogue from the Byzantine period had inscriptions in Greek and Aramaic, and mosaics, albeit of biblical themes, that attest to shared artistic traditions – and perhaps common cultures – with Christian Byzantines and Roman pagans. Perhaps we know the earth when we acknowledge our common debt to it.

They note the pagan presence – surprising to some – at the site, with mosaics of an Amazon warrior, Dionysus, and Heracles among others. All this sounds fairly inoffensive, but it conceals the site’s core history, namely that it was first a majority-Jewish city in late antiquity, with its name stemming from the Hebrew word for bird.

This theme continues elsewhere in the book. At Qasr el-Yahud, Jesus’ traditional baptismal site, they implicitly criticise the signage for first describing how this was where the Israelites crossed the Jordan River and where Elijah ascended to heaven, even though these events preceded Jesus’ baptism. Nor do they mention the meaning of Qasr el-Yahud, ‘Castle of the Jews’. Visiting Gamla in the Golan Heights, they note the existence of ‘yet another archaeological ruin of an ancient city’, without noting that it was a Jewish city destroyed in the First Jewish Revolt against the Romans.

These problems spill into their reflections on more recent events. At Rosh Hanikra, they write that the establishment of Israel made regional train travel impossible because it ‘severed the lines of communication between the different parts of the Arab lands in the Levant and beyond’, as if this was a passive outcome of the war, rather than a consequence of Arab states refusing to acknowledge the new country they had failed to destroy. At the ruins of the Lido, by the shores of the Dead Sea, they write that it was ‘established in the early sixties and a favourite haunt for Palestinian families before the Israeli occupation of the West Bank’, when in reality it was opened in the 1920s by Jews and Arabs in the area of Kalia, which was occupied and destroyed by the Jordanians in 1948.

Continuing their search for Nakba memorials, in the northern Israeli town of Kfar Kanna they find a monument that was unveiled in September 2000, a few days before the start of the Second Intifada, where the word Nakba doesn’t appear on the memorial. They also visit Tel Aviv’s Charles Clore Park, which was built on the ruins of the Palestinian neighborhood of Manshiya. ‘Every time we drive by the exquisite blue sea, Manshiya will emerge whole in our mind, and as it once was, before the Charles Clore Park was built.’ On the shores of the Sea of Galilee, at Kibbutz Ha’aon, they visit a memorial to two Turkish pilots who were killed in February 1914, delivering the first Ottoman airmail. The monument had been the initiative of Yerach Paran, a historian and a resident of the kibbutz, which was built on the ruins of the Palestinian villages of Al-Samra:

As we stood before the monument, we asked ourselves how was it possible that Paran, who died in 2020, should have worked for years to memorialise these two Turkish pilots, however heroic their endeavour and however sad their demise, while ignoring the tragic fate of the 300 residents of Samra, whose destroyed homes lay beneath his feet in his kibbutz home… We do not know Paran’s thinking but surmise that the recognition of Ottoman history poses no threat to Israel’s narrative while the Nakba does.

It’s hard to believe that they really don’t know his thinking, but the question deserves an answer, which is that Israelis do not accept Shehadeh and Johnson’s Nakba narrative. Irrespective of their suffering in 1948, the Israeli view is that the Palestinians were not innocent victims of Israeli crimes but active participants in a zero-sum war in which the Arabs did exactly the same thing to Jews as Jews did to the Arabs (for example in the Old City of Jerusalem or Gush Etzion). It is important to note the history of places like Manshiya and Saffuriya, but for Israel to commemorate the Nakba in the way Shehadeh/Johnson seek would be to falsely accept the country’s illegitimacy.

All this is a shame, because these omissions and evasions lessen the impact of fascinating sections about little-known aspects of Palestinian history and heritage. Sites like Khan al Tujjar (Khan of the Merchants) near Mount Tabor, one of 160 khans in Ottoman Palestine, now forlorn and neglected next to Highway 65, at least in part because it’s not a Jewish site. In Mea Shearim, they find the Nabi Ukkasha Mosque and Tomb, named for an Islamic holy man who came to Jerusalem with the Caliph Omar in the seventh century, although it is believed that Husam al Din al Qaymari, a commanding officer in Saladin’s army, is actually buried there. More recently, an unofficial sign has been placed at the site that reads ‘The Tomb of Benjamin, son of Jacob’, based on a reference in a medieval text that Benjamin was buried ‘opposite the Jebusite’, which some believe refers to Jerusalem. In reality, though, there is no chance that this is the tomb of Benjamin or any other Jewish figure.

While the occupation rightly gets the lion’s share of the blame for the damage to Palestinian heritage in the West Bank (much of this material is also covered in Shehadeh’s earlier books), there is also a refreshing amount of self-criticism. In the Ramallah area, they note that 75 per cent of Khirbet Tireh, where two Byzantine churches have been discovered, has been destroyed by development, while nearby Khirba Raddana – settled since the early Bronze Age – has been replaced by a park. At Tell en Nasbeh, where another Byzantine church is located, a man passing by suggests that the sign was slashed because it was a Christian site. ‘Once again, the matter of interpretation’, they write, ‘conflict and animosity or simply decay’. Finally, they visit Al Samhan palace in Ras Karkar village, one of 24 ‘throne villages’ in the central highlands in the late Ottoman period. These were ‘county seats’ ruled by rural semi-feudal sheikhs who collected taxes and provided protection for the villages as Ottoman rule weakened. Leaving the area, they reflect sadly that the Palestinian Authority was little more than a modern incarnation of the throne village, ‘exercising an ever-weakening degree of autonomy and subject to a much more imposing central authority: the Israeli occupation’.

Shehadeh and Johnson write accurately that the political situation in the land has ‘deprived new generations from gaining an impression of the country as a geographic unit’. But while most Palestinians living in the West Bank are subject to Israeli restrictions on their movement, Shehadeh and Johnson can travel relatively freely, as their visits to sites like the Israel Museum or Baram/Bir’im in the Upper Galilee demonstrates. I would have been interested to learn how this ‘privilege’ impacts their understanding of the situation.

Reflecting on their travels from the partially destroyed Mamilla Cemetery, now the site for the deeply controversial Museum of Tolerance, ‘it became clear to us that confronting the denial of the experiences of the other, as well as connections – lost, remembered, present and threatened – are what unites our explorations… Layers of peoples and civilisations – to be cherished rather than reduced to one simple story’. The simple story here could be both the classical Zionist narrative or Saeb Erekat’s claim that the Palestinians are the descendants of the Canaanites. The problem is that the idea of cherishing the ‘layers of peoples and civilisations’ can also be a simple story. The ‘land of three faiths’ idea, for example, ignores the fact that, to paraphrase something Matti Friedman wrote in The Jewish Review of Books, the land was only of interest to Christians and Muslims because it was of interest to Jews first, while focusing on this fact to the exclusion of all else ignores the fact that the Palestinians have also irrevocably shaped the land’s heritage. Both peoples have a deep connection to the land, even if the historical origins are different. The only hope lies in mutual recognition of the fact that both peoples justly see the land as the cradle of their emergences as distinct cultural entities. The denial of both Jewish and Palestinian heritage is an act of self-harm that prevents people from appreciating the history of the land in all its fullness; if we only see Tzippori and not Saffuriya, or vice versa, irrespective of our views of the political controversies, we are robbing ourselves of the only path to a sane existence here.