Calev Ben-Dor reviews three new books published to mark the anniversary of the brutal Hamas attack on Israel. As the anniversary of that unimaginably terrible day approaches, we, those who are alive, need to live. That’s not always such an easy task

Books under Review

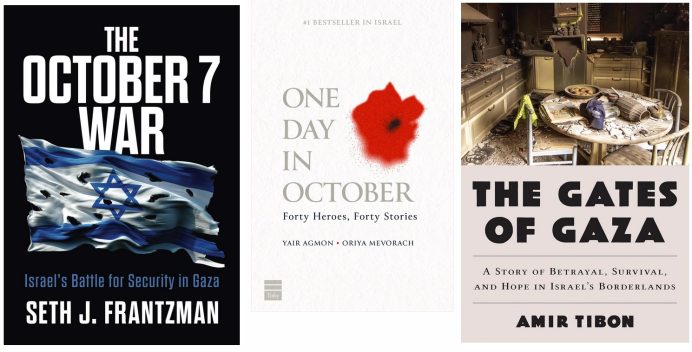

The October 7 War: Israel’s Battle for Security in Gaza, Seth J. Frantzman

The Gates of Gaza: A Story of Betrayal, Survival, and Hope in Israel’s Borderlands, Amir Tibon

One Day in October: Forty Heroes, Forty Stories, compiled by Yair Agmon and Oriya Mevorach

‘Ours is not a bloodline but a textline,’ Amos Oz and his daughter Fania Oz Salzberger tell us in their wonderful book, Jews and Words. So we should not be overly surprised that as the anniversary of the Hamas massacre on 7 October draws close, hundreds of thousands of words have been written to mark the event – 80 Hebrew books published in Israel so far –and help us better understand that day.

In different ways, One Day in October by Yair Agmon and Oriya Mevorach, The October 7 War, by Seth Frantzman, and The Gates of Gaza by Amir Tibon do just that.

Israel’s mistaken ‘conception’

A journalist who has spent time living in and travelling the region writing on military tactics and strategy, Frantzman does a good job at mapping out the conception that led to the IDF’s failure to prepare for the Hamas attack. He notes the building of the concrete underground barrier, which Israel came to over-rely on, which was ‘designed to deal with the 2014 threat’ (namely Hamas’ offensive tunnels that entered Israeli territory). That was a blunder, according to Yossi Langotsky, an Israeli geologist and colonel in the reserves who consulted on how to handle the tunnel threat, ‘along the lines of the Maginot line’. ‘The smartest thing was to harness geophysics to the fight against tunnels to place sensors and detectors in the ground, which would warn of movements related to the ground’ Langotsky says. ‘But this is not the ultimate solution, because there is no one ultimate solution.’

The Netanyahu-led government and the security establishment believed Hamas to be uninterested in war. Frantzman writes of how in September 2023, Israeli security officials travelled to Doha in Qatar to discuss more funding to Gaza and allowing more daily labourers from the Strip into Israel. Israel’s assessment was that Hamas was deterred and any escalation in rhetoric or threats was actually for money and work. ‘Hamas had been defeated in 2002, 2009, 2012, 2014, and 2021, and it would be defeated again. Also, Hamas had not changed. It didn’t have new weapons.’

Frantzman also describes the problems on the day itself. The gaps in how the IDF warnings were communicated to the top brass. How Hamas’s attack on the army base at Reim blinded the IDF to the extent of the attack. In Kibbutz Be’eri, Arik Kraunik, who had the keys to the armory where the security team could access rifles and armored vests, was killed in the initial attack before he could distribute the gear and weapons. This left the rest of the dozen members of the team unable to obtain more rifles to defend the community. ‘The security team kept fighting, but they had one rifle, which passed from one wounded man to another as members of the team became incapacitated,’ Frantzman explains.

The challenge is how one can effectively analyse a war that is ongoing and whose end is uncertain. And for some readers, the various units and places may become hard to follow – the book is filled with details about Shayetet 13, Duvdevan, Yahalom commandos, Yasam police commandos, Shaldag, Sayeret Matkal and others. (Those who enjoy learning about the differences between the seventy-ton tracked Namer APC, which uses a Merkava tank chassis, and the Eitan APC which was the ideal replacement for the M113 armored personnel carrier are in for a treat.) But those looking for details about the years preceding the attack, the day itself and the last 12 months of military operations will undoubtedly learn a great deal.

Surrounded by super-heroes

One Day in October meanwhile introduces us to 40 real-life Israeli heroes, in their own words (or the words of their loved ones). Many include broadly secular or national religious Jewish-Israelis: Aner Shapiro throwing out grenades seven times from the shelter (in which Hirsch Goldberg-Polin was also hiding) before the explosion of the eighth killed him; brothers Noam and Yishay Slotki who fought (and died) together protecting Kibbutz Alumim; fifty-four-year-old Chief Supt. Avi Amar, who fought in Sderot, Kibbutz Kfar Aza, and finally Kibbutz Be’eri where he was killed; Livni Ben-Yehuda, the first female infantry commander and head of a border defence battalion, who stood by the fence breach trying to stem the tide of terrorists entering Israel; retired IDF vet Eran Masas, 46, from Kiryat Ata near Haifa, who drove 200 kilometres to Sderot to help and ended up directing Nova survivors to safety and ultimately collecting bodies; and the story of Yotam Chayim, told by his mother, about a boy who overcame many difficulties before escaping Hamas kidnappers and tragically being shot by the IDF.

But the book also does a good job of featuring different groups within Israeli society: twenty-three-year-old Arab Israeli Awad Darawshe, a paramedic at the Nova Festival who refused to flee and believed he could talk Hamas down; Nasreen Yousef, a Druze mother who interrogated captured Hamas fighters, spoke to their commander on the phone pretending to be a sympathiser, and then told the IDF of their location; Bedouin minivan drivers Yosef El Zaidneh and his late cousin Abed al-Rahman Alnasarah who rushed towards the festival to rescue those fleeing; Ultra-Orthodox ambulance drivers who continued past IDF checkpoints to reach the wounded (‘if I’m going to drive on Shabbat’ one says ‘it’s in order to save lives,’) or Zaka volunteer Yossi Landau who recounted how the short stretch of road on Route 232 that usually takes 10 minutes to walk took him and his colleagues seven hours to traverse because of the number of charred bodies in the vehicles. (The Gates of Gaza describes that road as a ‘biblical scene strewn with corpses.’ Amir Tibon’s father Noam, who had spent decades in the army, later tells him that he had ‘never seen so much death in one place before.’)

All 40 stories are very moving (and I suggest having tissues handy to wipe away your tears) but two primarily remained in my memory. One was the testimony of Thomas Hand, the Irish father of nine-year-old Emily who was kidnapped from Kibbutz Be’eri and freed in late November (Emily’s memories are also featured in the book). Thomas recounts that when he went to meet Emily, he brought their dog, Jonesy ‘because I wasn’t sure she’d want to hug me.’ Throughout her time in Gaza, we learn, Thomas thought that perhaps Emily was angry with him (she wasn’t) for not being with her to protect her, and he partially fears their reunion. The other story is one titled ‘The Exact Opposite of All Those Hero Stories’ and refers to Shlomo Ron of Nachal Oz. As Hamas gunmen were about to enter the house, the 85-year-old Ron went to the living room to sit in his easy chair. Having shot and murdered him on sight, the terrorists assumed he was alone, and left the rest of the house. In his quick thinking and willingness to sacrifice, Ron’s actions allowed his family to survive.

The book is a telling reminder that the post-heroic society of many Western countries isn’t shared by Israelis (despite the perception that many Israelis dream of a high-tech exit and a move to Berlin or California). It also emphasises – as I try to remind myself – that as we walk in the streets in this country, we are surrounded by super-heroes. The country is full of them.

One tale of heroism that was not featured in the book is also related to Kibbutz Nachal Oz – that of retired Major General Noam Tibon, who with his wife drove to the Kibbutz to save their son Amir, his wife Miri and their two granddaughters Galia and Carmel. That story is the subject of the beautifully written The Gates of Gaza, by Amir himself, which alternates between the harrowing events of the day itself and the history of Nachal Oz, where Amir and Miri made their home in the aftermath of Operation Protective Edge in 2014. It’s a real page turner, and the reader is introduced to various characters over the years, several of whom are ultimately brutally murdered or taken hostage on the 7th.

On that dark day I was actually outside of Sorento, Italy on a family holiday. In the ensuing days, shocked, traumatised, and unable to get home, our hearts were in the East while we were in the West. For better or for worse, I chose not to delve too deeply into the gruesome details. Yet there was one story that consistently brought me close to tears every time I saw it – that of Noam Tibon fighting his way through the chaos and death to reach his family, banging on the door of their safe room and saying ‘saba hee-gia’ grandpa is here. Even as I write these words I choke up a little.

Moshe Dayan’s 1956 eulogy

Hovering amongst the pages is the eulogy that Moshe Dayan gave at the funeral of Roi Rotberg, the first security chief of Kibbutz Nachal Oz, and from where the book draws its title, the Gates of Gaza (a phrase also used in the Biblical Story of Samson.) In 1956 Rotberg was drawn out on horseback by Palestinian gunmen towards a nearby wheat field and then killed and mutilated and dragged to the Gaza / Egyptian side of the border.

‘Not from the Arabs of Gaza must we demand the blood of Roi’ Dayan says ‘but from ourselves. How our eyes are closed to the reality of our fate, unwilling to see the destiny of our generation in its full cruelty. Have we forgotten that this small band of youths, settled in Nahal Oz, carries on its shoulders the heavy gates of Gaza, beyond which hundreds of thousands of eyes and arms huddle together and pray for the onset of our weakness so that they may tear us to pieces — has this been forgotten? For we know that if the hope of our destruction is to perish, we must be, morning and evening, armed and ready.

A generation of settlement are we, and without the steel helmet and the maw of the cannon we shall not plant a tree, nor build a house. Our children shall not have lives to live if we do not dig shelters; and without the barbed wire fence and the machine gun, we shall not pave a path nor drill for water. The millions of Jews, annihilated without a land, peer out at us from the ashes of Israeli history and command us to settle and rebuild a land for our people. But beyond the furrow that marks the border, lies a surging sea of hatred and vengeance, yearning for the day that the tranquility blunts our alertness, for the day that we heed the ambassadors of conspiring hypocrisy, who call for us to lay down our arms…

We mustn’t flinch from the hatred that accompanies and fills the lives of hundreds of thousands of Arabs, who live around us and are waiting for the moment when their hands may claim our blood. We mustn’t avert our eyes, lest our hands be weakened. That is the decree of our generation. That is the choice of our lives – to be willing and armed, strong and unyielding, lest the sword be knocked from our fists, and our lives severed.

As Tibon writes, Dayan’s eulogy – primarily the part about demanding the blood of Roi from ourselves rather than the Arabs of Gaza – is a stinging rebuke to Israel’s current generation of politicians. ‘Our own leadership has failed to take responsibility for the biggest security failure in the history of the state of Israel,’ Tibon says.

Indeed, just as Jews are commanded to do over the High Holy Days, it demands we carry out a cheshbon nefesh, a reckoning of our own actions and policies.

But of course the eulogy has other components too: to not avert our eyes from the hatred emanating from Gaza. To be armed and ready. To remember those Jews looking at us from the ashes of history commanding us to secure a homeland (little could Dayan have imagined the Israelis of 2023 who were turned to ash).

How to balance those components Dayan doesn’t tell us. It’s not something any politician, soldier or book has the answer to.

‘Since we were alive, we were going to have to live’

Where does this leave us? Tibon recounts that after his rescues, with the electricity returned, and neighbours congregating in his apartment,

Ruti [a 70 year old neighbour], with a dead serious look on her face, approached Miri in the living room. In front of everyone, she asked where she could find a pot for cooking pasta. Miri seemed confused. ‘Pasta? what are you talking about,’ she asked. But Ruti insisted. ‘I know we’ve all had a very long day,’ she said, ‘but there are ten children sitting in that little room, and they need to have dinner.” Tibon continues. ‘As I watched people eating – the children sitting on the floor of the safe room, their parents in the living room, and the soldiers out on the porch visible only through the cracks that the terrorists’ bullets had left in our windows – I realized that Ruti had just done us all huge favor. She had told us, in a very few words, that since we were alive, we were going to have to live.’

As the anniversary of that unimaginably terrible day approaches, we, those who are alive, need to live. That’s not always such an easy task. In his introduction to One Day in October, Yair Agmon writes of his state of mind in the weeks and months after the terrible day. ‘This book lifted me out of depression,’ he writes. ‘These heroes don’t know it, but they saved my life too.’

He is likely not the only one.