Lyn Julius is the author of Uprooted: how 3,000 years of Jewish civilisation in the Arab world vanished overnight, published by Vallentine Mitchell in 2018. The Farhud is the name given to the Nazi-inspired massacre of Jews in Iraq in June 1941. As Julius notes, ‘it is only in the last 15 years that the term has become familiar to a niche English-speaking readership – thanks in part to the following three books.’

The 7 October Hamas attack has been commonly described as the worst massacre since the Holocaust. But among Jews born in Arab and Muslim countries, it has stirred memories of deadly violence perpetrated by local mobs. The pogroms recall a familiar modus operandi –rampages replete with slaughter, burnings, rape, mutilation, destruction, looting. One of the most serious was the two-day Farhud (A Kurdish word meaning murderous breakdown of law and order): the June 1941, Nazi-inspired massacre of Jews in Iraq. Some 179 identified Jews were murdered (some estimates put the toll as high as 600, or even 1,000), 2,000 were wounded and 900 homes and 586 Jewish-owned businesses were destroyed.

This episode shook the 150,000-member Jewish community as never before. The Jews had been settled in the region for almost three millennia – since the Babylonian exile. The Farhud sounded the death knell for the Jews of Iraq. 120,000 fled ten years later. Other riots followed (Libya in 1945 and 1948 – 148 Jews dead), Aden (87 Jews dead) Syria (the Aleppo Great synagogue destroyed), Morocco (48 dead) as Jews felt the full force of state-sponsored incitement and persecution in Arab states.

Mob violence or the threat of violence on the eve of Israel’s declaration of independence was a key factor in undermining the Jewish sense of security in a world already buffeted by the forces of Arab nationalism and anti-colonialism. The result was a mass exodus and the extinction of age-old Jewish communities.

Although the Farhud was a trauma already deeply embedded in the collective memory of the Jews of Iraq, it is only in the last 15 years that the term has become familiar to a niche English-speaking readership – thanks in part to the following three books.

In the Alleys of Baghdad by Salim Fattal (Shlomo Levy, 2012)

Traumatised by the Farhud, Iraqi-Jewish youth diverted away from nationalism into support for two movements: Zionism – seeking salvation in a future Jewish state, and Communism – seeking a universalist, anti-nationalist and anti-colonialist revolution to resolve the Jews’ plight. In the end the Jews, including the Communists, adopted the Zionist solution.

Salim Fattal became a member of the Iraqi Communist party. Brought up by his widowed mother in Baghdad’s old Jewish quarter, his autobiography records a childhood of deprivation and tragedy. Even on arrival in Israel he was stigmatised for his Communist past. In time he acquired two university degrees and rose to become director of Israel’s Arabic broadcasting service.

But the defining event of his life remained the Farhud, which he vividly recalled as a boy of 11 in his memoir In the Alleys of Baghdad. (By a twist of fate he died on the Farhud’s 76th anniversary). The book is a corrective to the nostalgia of Jews from more prosperous families. During his career, Fattal conducted 100 televised interviews with Farhud survivors in Israel. In his later years, Fattal devoted much energy to fighting revisionist accounts of Jewish-Arab coexistence which downplayed antisemitism in Arab countries ‘to flatter’.

Fattal’s uncle Meir, together with his business partner Nahum, were murdered on the first day of the pogrom. Their bodies were never found.

Barricaded in their home, Fattal’s family decided to bribe a policeman to protect them from the mob.

We could see them right under our noses and if they had decided to attack us then, no one could have stopped them as it was very easy for the rioters to move from roof to roof. So we called our armed policeman from outside and begged him to fire a few bullets in the air to scare them away. Our policeman insisted on more payment and my Uncle Naim argued that we had already paid him generously. But our policeman kept repeating: ‘How much will you pay?’ while our situation was getting more and more threatening by the minute. Finally they agreed upon half a dinar per bullet. Had he refused, we would have taken his gun. The policeman fired two shots and paused and then two more shots, until he saw the rioters move away.

The Jews could only rely for their security on venal policemen or on the kindness of a neighbour, so demonstrating the precariousness of their existence. Not only that, but no one in the wider world seemed to care. ‘Their cries never escaped the bounds of the Jewish quarter, but went down into the grave with the victims’, Fattal laments.

In a postscript, Fattal reflects that ‘the massacre of Arabs by Arabs is a mere trifle. A pogrom against the Jews is just a natural disaster, inevitable, a divine decree beyond human control.’

Along with the majority of Iraqi Jews, Salim Fattal left Baghdad in 1950 for Israel. The city of his birth was frozen in his memory as a ‘place of gallows and pogroms’. Beset by feelings of disappointment and anger, he did not think about it or miss it.

The Farhud by Edwin Black (Dialog, 2010)

If Salim Fattal ‘s memoir is a deeply personal account by a Farhud survivor, Edwin Black’s The Farhud is a wide-ranging work examining the historical background and geopolitical causes leading up to the massacre, which he describes in granular detail. The Farhud set the stage for the devastation and expulsion of a million Jews across the Arab World.

Writing the book was clearly not a pleasant experience. Black’s opening words are: ‘This book is a nightmare … I regret that I was the one who had to write it. I hope it never becomes necessary to write another like this one.’

Edwin Black has achieved fame as an investigative journalist and author with more than 200 books to his name. He has probably done more than any other mainstream writer to extricate the Farhud from historical obscurity. Samuel Edelman, in an afterword to Black’s book, admits he had never heard of this terrible event until 2003.

As a specialist in genocide and hate, with a particular interest in Nazism, Black was the ideal writer to investigate the wartime Arab-Nazi alliance which led to the Farhud, and the particular contribution of the pro-Nazi Palestinian Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini. Engineering more escapes in his lifetime than Houdini, the Mufti fled to Baghdad from British-controlled Palestine after the failure of the Arab Revolt in 1939. In Iraq for two years, he inspired the Golden Square pro-Nazi officer ring, making repeated attempts to throw off the pro-British government. They finally seized power in April 1941 until British forces put them to flight. But the Golden Square’s parting shot was to wreak Farhud mayhem and murder among the Jews.

Edwin Black has helped to gain recognition of the Farhud as a Holocaust event, fuelled by Nazi incitement. Aghast that the Farhud did not even figure in the historiography of the Holocaust, Black badgered the US Holocaust Museum in Washington DC into acknowledging the Farhud. He created International Farhud Day to be observed annually on 1 June .

As with other Black books, The Farhud is exhaustively researched – Black’s trademark technique is to deploy an army of data-gathering assistants in archives and libraries across the word.

Written in a colourful style for the non-academic reader, The Farhud begins by hurtling through 2, 600 years of Jewish history in Mesopotamia, the ‘cradle of civilisation’. It then bifurcates into an account of Zionism and the Yishuv on the one hand, and the colonial politics of oil on the other. Here, Black is on familiar territory, charted in his two earlier bestsellers, Transfer Agreement and Banking on Baghdad. Black’s thesis is that these two factors explain two strands of Arab hatred, fusing into the Arab-Nazi axis.

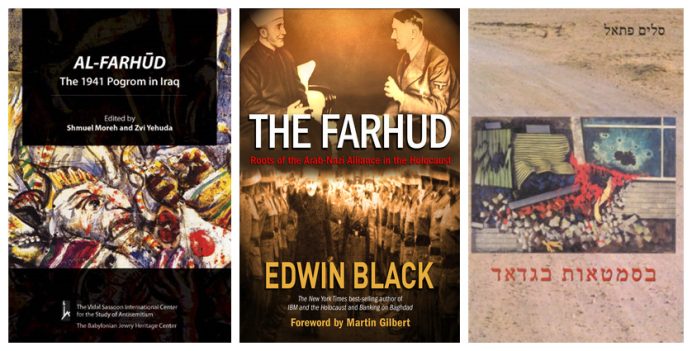

Al-Farhud: the 1941 pogrom in Iraq, edited by Shmuel Moreh and Zvi Yehuda (Hebrew University, 2010)

Published by the Vidal Sassoon International Centre for the Study of Antisemitism, directed by Robert Wistrich until his death, this book was published as a revised version of the Hebrew edition first published by the Babylonian Jewry Heritage Centre.

The authors, the late Professor Shmuel Moreh and Dr Zvi Yehuda, were Farhud survivors who devoted much of their lives to documenting the history of the Jews of Iraq. The book is an anthology of essays on the pogrom and the events leading up to it. It sheds new light on German activity against the Jews of Iraq and their responsibility for the pogrom. It contains documents not previously published, a map of the places in Baghdad where rioters attacked Jews and an updated list of known names of victims of the Farhud.

An essay by the renowned LSE professor Elie Kedourie casts light on the Basra riot preceding the Farhud. Stefan Wild deals with the influence of National Socialist propaganda on Arab youth movements and political parties and the attempts to translate Hitler’s Mein Kampf into Arabic.

There is also a first attempt to clarify the position of the Arab communists in Iraq, who were opposed to anti-Jewish persecution, and the reaction of Jewish leaders in mandatory Palestine to the Baghdad pogrom.

Professor Moreh himself surveys the Farhud in Iraqi-Jewish poetry, memoirs and novels.

Most fascinating of all is Moreh’s exploration of the decisive role played by the Palestinians and Syrians who entered Iraq in 1939 along with Mufti. They spread the libel that Jews were a disloyal and degenerate minority, thus laying the groundwork for the massacre. Indeed, Moreh calls the Jews of Iraq the first victims of Palestinian Arab nationalism.

Thus he sees the Palestinian jihad as the continuation of a campaign of violence which began with Iraqi youths hurling stones at the Jews in the streets of Baghdad. Al-Farhud restores to the Arab war against Israel an important dimension, ignored or neglected by commentators or historians: Jews outside Palestine were singled out for punishment well before the creation of Israel in 1948.