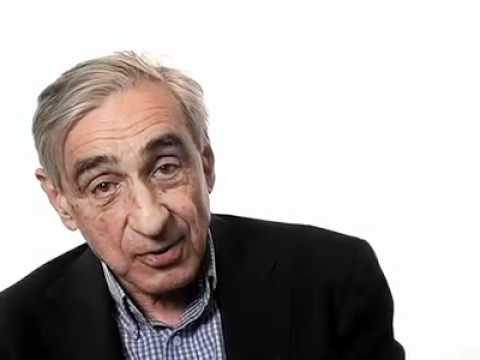

Stephen de Wijze is Senior Lecturer in Political Theory at the University of Manchester. He writes in praise of the political philosophy of Michael Walzer, as captured in Justice is Steady Work: A Conversation on Political Theory, by Astrid Von Busekist and Michael Walzer, published by Polity Press in 2020.

Justice is Steady Work is an excellent in-depth discussion of the life and work of Michael Walzer, one of the foremost political thinkers of the last 50 years. Astrid Von Busekist, a professor of political theory at Sciences Po in Paris, engages in a very informative book length dialogue with Walzer, delving into his personal background and the motivations for his academic pursuits in political and moral theory in addition to his longstanding political activism. In this comprehensive discussion, she converses with Walzer on the full range of his interests, eliciting rare and valuable insights into the goals and their motivations behind his considerable academic opus, as well as his writings as one of the most prolific public intellectuals. Those who are familiar with Walzer’s work will know that he covers a wide range of topics, which include his ground-breaking work on Just War Theory, his approach to how to properly engage in social science and political philosophy, his views on toleration, multilateralism and cooperation, the much vexed Israel/Palestine problem, his work on distributive justice and, finally, his latest project on the history of Jewish political thought.

This extensive oeuvre easily places Walzer among the great contemporary academics and one of the foremost public intellectuals of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. What makes Walzer stand out among even his distinguished peers is the methodology he adopts for engaging in social science and philosophical analysis. He is a philosopher storyteller and optimistic social critic who combines theory, history, anthropology and much more in his attempt to grapple with important political events of the day. It sets him apart from his rightly famous contemporaries such as great analytic political philosophers John Rawls and Robert Nozick, whose theories of justice have dominated the field of political theory from the second half of the 20th century onwards. Walzer’s approach to understanding political issues – his methodology – provides wisdom as it engages with the constraints of real situations without seeking to impose a grand theory on the complicated and messy lives of actual people. It is this approach I find especially useful and enlightening as it provides insights, for example, into how wars can be justified or not, how to define equality in pluralistic societies without imposing a grand ideal theory developed in the offices of academics who are excellent at reasoning but don’t take sufficient notice of the messiness and complexity of actual human affairs. (I think of this as the difference between being ‘clever’ and being ‘wise’.) Walzer’s approach entails deep wisdom in the way it seeks to understand the irreducibly complex, inconsistent, and often shambolic state of human affairs. Analytic philosophy has over the last century tended towards focusing narrowly on the theoretical arguments which begin by using idealised assumptions that have little or no purchase in the world as we find it today. Such debates tend to focus on establishing clear principles, and tend to ignore or downplay the often inconvenient, complex and messy state of the real world that empirical investigations reveal. They contend that the need for ideal theory is paramount, and once a set of principles are consistent, coherent and supported by arguments, their application to the real world becomes relevant (although in fact few political philosophers follow through with an examination of the efficacy of applying such principles to the real world). Walzer’s approach is quite different and refreshing. He eschews theoretical assumptions and hypothetical scenarios (some which are based on distinctly bizarre thought experiments), preferring to use actual examples and case studies from his work in anthropology, sociology and political history. Theorising must begin, Walzer insists, in the muddled complexity of human social life. Only then can we provide the insights into moral and political issues that will be germane and applicable to actual people and their actual communities.

But Walzer’s shift away from the analytic method of doing philosophy did not lead him towards the opaque and often impenetrable prose of the continental tradition of philosophy as found in the work of Kant, Hegel, and others. Nor does Walzer engage in the deliberately vague and often incoherent gibberish of post-modernism. His prose is always clear and easily accessible for the reader. He offers thoughtful and measured insights supported by historical or anthropological case studies. Walzer provides stories to frame his claims, and to read his work is to be immersed in a sensitive account of human virtues, vices and contradictory behaviour, in addition to how historically difficult problems have been tackled by thinkers and practitioners. I will return to say more about Walzer’s methodology and style of writing later in the review.

At this point I should confess that I am a great admirer of Walzer’s work, as will be obvious from my earlier remarks. He is among the best-known and most prolific Western political philosophers of the last 60 years, and is still active today, writing, campaigning and generally engaging with contemporary issues at the grand age of 89. Walzer was born in 1935 in the Bronx, New York, the grandson of Jewish Galician and Lithuanian immigrants. He grew up in a Jewish neighbourhood in Johnstown where his primary influences were the Jewish social milieu and his parents’ left-wing political views. Both these influences remain central to his adult writings to this day. Walzer has had a distinguished career. He has held positions at Harvard and Princeton Universities and is presently Professor Emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton. His work has been deeply influential, and he has been responsible for sea-changes in the way several important issues in political theory and ethics are viewed today. I have spent a great deal of my academic life reading Walzer’s work and building on his insights, while arguing that some of his claims about distributive justice, just war theory and the problem of dirty hands are problematic and need revision. But whatever my criticisms, what I have found most profound about his work is his methodology for engaging in political and moral theorising.

My first encounter with his unusual approach to moral and political theorising was reading his seminal article ‘Political Action: The Problem of Dirty Hands’, published in 1973 in the journal Philosophy & Public Affairs. I encountered this article while researching the constraints of moral theory on effective political action (realpolitik), and his account of the problem of ‘dirty hands’ was a revelation. I was unhappy with the standard deontological (duty based) and consequentialist moral views on this issue, and Walzer’s provocative paradoxical alternative view seemed to me to clearly resonate with common sense even though it clearly violated the standard ways of thinking about ethical dilemmas. His claim, in a nutshell, was that when faced, as is often the case for politicians, with a deep and irreconcilable clash between deontological and consequentialist moral obligations, the best that can be done is to accept that there is a moral paradox such that to do the right thing will result in a moral violation and the dirtying of one’s hands. In short, politicians sometimes face scenarios where good and well-intentioned persons are required to do wrong in order to do right. Perhaps his best-known example of this is encapsulated by the ‘Ticking Bomb Scenario’ (77). Here a terrorist has planted a bomb in a heavily populated city and while in the custody of the police informs them that it will explode in the next 24 hours. He refuses to reveal the whereabouts of the bomb which if it detonates will undoubtedly kill many people. The Prime Minister is asked to authorise torturing the terrorist to find the bomb in time and save lives. This leaves a terrible moral dilemma for the Prime Minister. She knows that torture is always wrong and that it should never be used by any official of a decent and civilised society. Yet she also has a fundamental duty to protect those in her care and can only do this by violating this prohibition against torture. She is damned if she orders torture and damned if she does not. Walzer’s key insight here is that her duty to protect will give her a moral reason to violate an absolute principle. She will be moved by moral considerations to commit a moral violation – and she unavoidably becomes morally polluted for having so acted. Without delving into the details of Walzer’s argument here what is important to note is that he is acknowledging a challenge faced by politicians which rejects the neat reductionistic answers insisted upon by deontologist and consequentialists who, despite the lived reality of those facing such a dilemma, insist that no such dilemma exists. Their moral theories simply will not allow such a dirty hands scenario to be possible in their moral schemas. To think that one exists is to fail to grasp that the proper attention to the ideal theory will dissolve the apparent or prima facie moral conflict. Walzer, in contrast, is not arguing from an idealised theoretical position about what is morally required in such circumstances, but rather seeks to understand historical and current unavoidable dilemmas faced by politicians. The ticking bomb scenario is not hypothetical for Walzer but prompted by cases which arose from the war in Algeria between the French army and the FNL terrorists. He was seeking to understand the complex and messy moral state of play in this terrible conflict situation, but without insisting that the solution fit into neat abstract moral principles. Agents facing this dilemma are not best served by telling them that torturing is a moral act, or that letting people die through inaction is the right thing to do. The reality is that no matter how a good person acts in such circumstances, there is moral fallout, and the agent will rightly feel the unavoidable moral pollution that results. Walzer’s dirty hands account was dismissed by most analytical philosophers (apart from Thomas Nagel who was willing to think about the paradox of dirty hands) as poor and confused moral theorising. Walzer jokes that for most of his colleagues, his paper on dirty hands was a clear example of philosophical incoherence: an example for students not to follow in their study of ethics (77). Yet Walzer’s view resonates with political practitioners everywhere, and the dirty hands scenario is intuitively understood by most people who are not concerned with abstract ethical theories. It fits better with the phenomenology of ordinary people who are faced with such moral dilemmas. Again, Walzer wants to begin theorising from the experiences of those operating in the untidiness of the real world rather than impose abstract principles on it.

Von Busekist’s Justice is Steady Work discusses Walzer’s influential work over the last six decades. It consists of nine chapters and a Coda. The first chapter entitled ‘Who Are You Michael Walzer?’ explores Walzer’s childhood and background seeking to understand the social and political milieu in which his world view and enduring interests developed. It reads like an interview and differs from the following eight chapters which are set out as a dialogue between two political philosophers. Throughout the book, Von Busekist’s questioning skilfully elicits from Walzer himself just how the lasting and profound influences on him developed as he was growing up in the Bronx, New York in a Jewish socialist home, and how this led to his humanistic and pragmatic philosophical approach. These influences forged a body of work which ‘is tied to the preservation of particulars, to the respect of local values, and to the defense of pluralism’ (15, all numbers in brackets refer to Justice as Steady Work).

The following eight chapters focus on Walzer’s most influential writings – both as an academic and as a political activist. The dialogue format adopted by Von Busekist continues the informal way to explore the core convictions which prefigure Walzer’s work. It reveals the convictions he holds in stories, jokes and anecdotes that occurred from his boyhood until present day. There are references to his different mentors’ advice, the encouragements of friends and colleagues, tales about his meetings with key political figures of his day, humour concerning how his arguments were received by colleagues working in political philosophy, and much more. These insights are not in themselves arguments for his particular claims themselves but provide the important private influences and thoughts that do not appear explicitly in his writing. For this reason alone, whether one is familiar with his work or not, the book is a fascinating and engrossing experience.

It is useful to briefly summarise the focus of each chapter. Chapter two begins the dialogue with an exploration of Walzer’s political activism; in particular his work on civil rights and opposition to the Vietnam War when he was part of the Anti-War Movement. Here we can already see the beginnings of Walzer’s concern with a reductive Marxist account of the world with his critique of some versions of left-wing politics. He argued that left-wing discourse needed to inject humanity into its claims, or it would otherwise tend to be ‘too rigidly correct’ (57). Walzer strongly rejects reductionist accounts of how the world is or ought to be and was therefore strongly opposed to the ‘correct’ ideological position held by some among the Left. This conviction arose in large part due to the shameful support of Stalin and his policies by many of the left despite clear evidence of his horrendous crimes. Walzer believes in and advocates for a different kind of socialism, one that is emancipated from orthodox Marxism and seeks to provide a form of social justice based on democracy, justice and social equality. Leftists, he argues ‘must pursue a politics of kindness…raising consciousness, forming coalitions, building a majority, making lives better, one step at a time (170).’ It is this fundamental commitment that inspired the title of the book Justice is Steady Work.

The third chapter moves to a discussion of Walzer’s involvement with the influential left-wing journal Dissent. Dissent was started by Irving Howe (Walzer’s mentor at Brandeis University) in 1954. It was under Howe’s influence and tutelage that Walzer became a ‘fiercely anti-Stalinist’ leftist (58). Dissent became a journal for those on the left who were emancipated from the Marxist orthodoxy but remained committed to left-wing goals and aspirations. We can see here one of the main influences on Walzer’s intellectual development, which shaped his methodology for doing political philosophy. As co-editor of Dissent, Walzer urged that contributors to the journal engage in a closer way with contemporary American politics and advocate for ‘the left wing of the possible’. His concern with contemporary political problems which he wanted to explore from a social democratic perspective is a constant in his life steadfastly remaining deeply critical of any left-wing version of authoritarian politics. Walzer is a social democrat and is always clear that he was concerned not only with the authoritarian pathologies of the Left, but also their ‘root and branch anti-Americanism’ and deep ‘hostility to Israel that often brings with it all the antisemitic tropes’ (68).

Chapter four explores the background influences on Walzer’s seminal contribution to the field of Just War Theory. The enormous success of his book, Just and Unjust Wars, came as a great surprise to him as it almost immediately became an indispensable source and companion for anyone working on this topic. Its adoption as required reading by The United States Military Academy at West Point for all officer training in the US army is testament to the enormous impact his work here had, not only to theorists but also to those engaged in the practice of war itself. On the theoretical side, the subsequent plethora of books and articles written on this topic acknowledge Walzer’s seminal contribution whether or not they seek to argue that his account is flawed or misconceived. As with other topics that interested Walzer, his concern with the outlining as clearly as possible the laws of war were driven by contemporary political events. The events in play here were the accusations that he was confused and biased, given his opposition to the Vietnam war but support for the Israeli Six-Day war. Walzer’s response was to write Just and Unjust Wars which set out the relevant distinctions for showing which wars are justified and which are not. This book delves deeply into the history of warfare and uses actual examples from the history of warfare to make clear and plausible distinctions about when it is justified to go to war (just ad bellum) and what conduct is permitted in fighting the war (jus in bello). Again, Walzer’s methodological approach sets him apart from many political theorists working on this topic. For example, his approach is rejected by some just war theorists (who are referred to as ‘Revisionists’ such as Jeff McMahan) as too communitarian so paying insufficient heed to individual rights. Walzer argues for the ‘moral equality of soldiers’ in warfare insisting that the principles of jus ad bellum and jus in bello are separate. Consequently, it is not only possible but likely that one of the parties in the war will be fighting an unjust war but could be doing so in a morally permissible manner (or vice versa). McMahan, and his fellow revisionists’ reject this distinction since they argue that Just War Theory is an extension of the philosophical analysis of the ethics of killing applicable to individuals. This domestic analogy which informs revisionist accounts argues that individuals who are engaged in an unjustified action can never justifiably engage in violence. While this seems plausible if your model here is criminals fighting the police, it fails to understand the very nature of warfare as a collective activity where the soldiers themselves do initiate or justify the war. Walzer sardonically pointing out that ‘McMahan’s theory of war would be right if war were a peace time activity’ (80). Walzer also notes that McMahan won the argument among philosophers but that he won it among the Army, Navy and Air Force (79). This, I am sure, pleased him enormously.

Chapter five moves to a discussion of Walzer’s work on national sovereignty and its tension with the necessity for multilateralism and international cooperation. Walzer’s position here differs from the default internationalist view common among those on the left. He argues for the importance of nation states to protect their citizens and enable them to lead an independent existence free from external domination. Walzer rejects the cosmopolitan argument that there is no moral difference between peoples and hence no greater obligations to those of our own group or community. This view Walzer sees as naïve at best as it ignores the reality of human relationships and the need for political entities that protect cultures, languages and religions. Drawing from lessons in history, anthropology and literature, and understanding human flourishing as strongly tied to membership in a community, Walzer argues that the cosmopolitan view erroneously assumes a notion of persons endowed with abstract rights unconnected to the communities to which they belong. Rights, duties, purpose, meaning, a sense of belonging, and more are intimately tied to membership in a community and cannot be ignored when theorising about social and political issues. This does not mean that Walzer rejects universal obligations incumbent on all persons. But his idea of how we arrive at such universal obligations is based on long traditions within communities and a shared recognition that human beings need protection from the predations of others. They need to be defended, as Stuart Hampshire would put it, from the Great Evils – both natural and social – which would make any worthwhile life impossible. The justification and need for moral principles arise from human vulnerability to the social evils. This shared vulnerability resulted in all societies constructing moral rules to protect their members from the social evils of murder, rape, torture and so on. Walzer has no interest in scrutinising the foundations of such rules since for him ‘the moral universe simply exists, we inhabit it’ (118). So, while communities and peoples can acknowledge universal moral obligations this does not render otiose the fundamental need for membership in a community in the form of a nation state. This position arises from Walzer’s strong communitarian instincts that thriving communities, with their unique customs, language and religion, need the physical protection of a state where they can continue to flourish by expressing and developing their common culture. As Von Busekist points out, Walzer understands Zionism in this way, as both a form of universal statism and secular nationalism (91). He advocates for a two-state solution to the Israel/Palestine problem because he believes that both peoples need a nation state to champion and protect their respective cultures and aspirations. Yet Walzer is also rightly wary of the excesses of exclusionary nationalism, so there also needs to be a recognition of international norms and universal social ties which cross state boundaries and link all civilised societies together. It is all too easy for nationalisms to become toxic resulting in prejudice and discrimination against minorities and foreigners. Walzer’s solution here is to argue that it is possible to be both statist and internationalist at the same time. Indeed, he points out that the assertion that everybody needs to be a member of a state is itself an internationalist claim. Furthermore, states need to have multilateral cooperation with other nation states thereby creating and supporting international organisations which foster global security and economic stability.

Chapter six raises the very difficult and much vexed issue of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Again, the dialogue explores Walzer’s lifelong love and support for Israel with his deep and consistent criticism of many of the Israeli government actions. He is, to put it mildly, no fan of the current right-wing government nor of successive Palestinian leaders. He points out that the Palestinian quest for a state has been tragically undermined by the ideologically driven and corrupt leadership of the PLO along with the Islamist fascism of Hamas. But this said, he is also deeply concerned with the knee-jerk anti-Israel stance taken up by a great deal of those on the Left. It is less than helpful to characterise this conflict in Manichean terms; when sections of both the Left and the Right do this it is a great disservice to everyone involved in the conflict. I write this paper while war rages between Israel and Hamas after the atrocities of 7 October. Great swathes of the Left and the far Right confirm his great fear about their simplistic Manichean approach to perhaps one of the most complicated political and military conflicts over the last 8 decades. This one-dimensional approach not only lacks nuance, clarity and a proper sense of events on the ground, but also inflames the situation, and this has deadly consequences for those involved in the actual fighting. Some on the Left who argue that Israel is an illegitimate colonial state, dismiss, ignore or downplay the horrors of the worst terrorist attack by Hamas since Israel’s founding. When they do condemn these atrocities (and there are a significant proportion that won’t even do this), it is to allow them to blame Israel for all the violence and death that followed in its wake. Hamas’ actions in the war, with its use of civilian shields and civilian facilities to fire on Israeli soldiers, is seen as legitimate resistance to an unjust invading force. In their Manichean world view ‘evil Israel’ (and more broadly Jews worldwide who support Israel) are always at fault and deliberately commit the very worst crimes imaginable. Hence the endless repetition of the patently false claim that Israel commits genocide. This frenzy of condemnation by sectors of the Left in large part arises from that knee-jerk anti-Israel and anti-Semitic worldview that concerned Walzer decades ago when he began writing for Dissent. The Left, Walzer argues (113), ought to be seeking a road to peace by defending the physical safety of Israelis while building the political reality needed for the process of reconciliation and a lasting peace. It is possible to criticise the Israeli government without seeking the destruction of the Israeli state or providing succour to genocidal Islamist groups such as Hamas.

Chapter seven focuses on Walzer’s approach to political theorising, and I will return to this issue below when discussing Walzer’s methodology. I believe this approach is the core reason his work is sensible and practical, yet also far-reaching and wise.

Chapters eight and nine focus on two important and influential parts of Walzer opus in political theory – his work on theories of justice and his recent discussions on the Jewish political tradition. Chapter eight discusses his account of distributive justice in a liberal democratic society. Here Walzer argues for a pluralist egalitarian account which offers the idea of ‘complex equality’ as the core driving force in ensuring a just society. Underlying this view are three central assumptions in Walzer’s communitarian approach. Firstly, political membership in a community is a fundamental social good and it informs the nature of how goods and services within this a particular community are fairly distributed. Walzer’s statism results from this insight as he believes that successful political membership minimally requires a territory which can be defended, coupled to social justice based on a community of values and shared understandings (136). In essence Walzer’s account of distributive justice differs from the universal philosophical approaches of his highly influential contemporaries such as John Rawls and Robert Nozick in that it is a relativistic account based on the fundamental and longstanding shared social understandings within communities. Walzer points out that his work was deeply influenced by Clifford Geertz’ writings on cultural anthropology (145). What matters for justice is not how abstract concepts such as liberty or equality are defined but how they are instantiated by the meanings of goods to be distributed within a determinate sphere of political and social life. Hence, Walzer rejects a universal ideal theory of justice based on simple abstract notions of equality or liberty. His pragmatic path uses empirical knowledge of the historical and contemporary practices of how social and political goods have been distributed and what the meanings of each good suggests about their appropriate and just distribution. Simple equality would demand the rigid equal distribution of all goods, but Walzer’s complex equality underlines the need for each good to be distributed according to their significance in the community. For example, educational goods will have a different fair distribution from political goods and from wealth and other commodities. In sort, how each of these goods ought to be justly distributed will depend on their common meaning and significance to those who make, distribute, and receive them. Walzer’s Spheres of Justice. A Defence of Pluralism and Equality is in essence, as he claims, ‘an anthropological theory of distributive justice’ (145).

Chapter nine focuses on Walzer’s recent and continuing project, which examines the Jewish political tradition and offers a political reading of the Hebrew bible. Again, we see the earlier concerns with pluralism come to the fore as Walzer argues that the inconsistencies and contradictory statements in the bible invite openness and discussion which in turn demand interpretation. To this end Walzer’s current project is to revive a Jewish political discourse that is focused on issues such as membership, equality, welfare, political authority, constraints on military power, and justice. His project in Jewish Political Thought is to foster a discussion on Jewish cultural nationalism which is both a liberal and pluralist project (161). Walzer’s answer to the threat of anti-Semitism, what he sardonically refers to as ‘the Jewish question’, lies in a Jewish cultural revival along with ‘democratic citizenship in the West and sovereignty in the Middle East’ (161). This work offers the wise exploration of the biblical text by an extraordinarily talented and mature independent thinker. Walzer’s lifelong concerns and interests pursued in his early works re-emerge in the enormous task undertaken to explain the neglected rich history of Jewish political thought.

Finally in the short chapter entitled ‘Coda’, which concludes this excellent book, Walzer offers a short reflection on what it is to live a life on the Left politically speaking. He insists that left-wing politics requires steady work which defends democracy, constitutional government, fairness and justice. It seeks to protect the most vulnerable in society, and importantly it must reach out beyond its own followers to form a coalition with centrist liberals and even decent conservatives. This will require compromise which is the raison d’être of good politics in a pluralist society.

As I promised earlier in the review, I now return to Walzer’s methodology when engaging in political theory, social criticism and public activism. Walzer’s work offers modest claims about progress and justice and crucially provides the indispensable wisdom often lacking in the clever arguments and rhetorical flourishes of analytic political philosophers and public intellectuals. Here I understand wisdom to be the ability to properly grasp the complex and often paradoxical nature of human lives whereas cleverness is the ability to engage in abstract thought using careful argumentation to rule out inconsistences and ambiguities.

Walzer is finely attuned to the difficulties and messiness of political and social theory. Busekist in her introduction to the book puts it this way: ‘Sensitivity to turmoil and attention to historical reality probably explains Michael Walzer’s unique place among the philosophers of his generation (6).’ Walzer’s work prioritises interpretation rather than discovery or invention. He does not seek to find universal moral laws or idealised concepts from which to then examine the state of society or political interactions. This, Walzer believes is essentially unattainable making the search for them heroic but misleading and largely futile. And in my view the golden thread that underlies Walzer’s work is located here. The deep wisdom he possesses arises from a profound conviction concerning the pluralist nature of our society combined with his call for, and patience with, small insights and gradual steady progress. He rejects the search for grand unassailable Archimedean truths which are then applied to the real world even when the empirical facts on the ground tell against them. Such grand narratives, which seek to reduce the highly complex interaction of people and communities to conceptually idealised frameworks or weltanschauungen, lead to serious errors in understanding the crooked nature of humanity, as Isaiah Berlin puts it. This distrust of grand theory and the method he adopts is beautifully captured in a metaphor he uses to describe his way of doing political philosophy.

The metaphor I have always used is: we are living in a house. We assume the house has a foundation, but I have never gone down there. I am trying to describe the living space, the shape of the rooms – and to suggest better ways of furnishing the house; sometimes I make suggestions for renovations. Morality is a social construction but it’s not, it’s not their social construction or our social construction, it’s a social construction over many, many centuries and it reflects our humanity, our common humanity, and so the basic rules of our morality are universal rules (118).

This is why Walzer contends that he is neither a philosopher nor a systematic thinker (119). He insists that his books are political arguments rather than ‘high theory’ (117). He is not interested in writing about the foundations of ethics since as he put it, ‘the moral universe simply exists, we inhabit it’ (118). Hence his focus on interpretation rather than discovery or invention, and his concern is to immerse himself in the moral and social world as it is already lived both in the past and in the present seeking common histories, shared social meanings while all the time respecting ‘the particularism associated with communitarianism’. To put it in terms which have dominated the writing on theories of justice in the second half of the 20th Century, the concern with seeking a clear view of the Right (the abstract and prior values of liberty, equality, fairness) over the Good (the thick values underlying different conceptions of the good life such as specific religious, political and other social values) is mistaken. Walzer’s communitarian approach rejects this method insisting the Right must be, in significant part, constituted by the Good as interpreted by a particular community. The core point of his Spheres of Justice was to repudiate the search for a single universal metric of distributive justice which in the case of Rawls, for example, was based on a hypothetical thought experiment of considering oneself behind a ‘veil of ignorance’ or with Marxists on a radical egalitarian principle.

I am not arguing that Walzer’s views on distributive justice are always correct, far from it. His notion of ‘complex equality’ has many salient criticisms which need to be addressed. His account of membership in communities is problematic, especially in complex societies where we have class, race, and gender differences. In these societies, who decides which meanings of goods is correct in divided societies? Similarly, Walzer’s relativist account poses problems that are common to all relativist moral claims. Could the inequality of women in some societies with traditional religious adherence be just and fair given the different shared meaning of social goods and their distribution? Walzer is well aware of these problems and seeks to address them without abandoning his methodological approach. His book Thick and Thin: Moral Argument at Home and Abroad revisits the arguments in Spheres of Justice by exploring the distinctions between two related but different kinds of moral arguments; those that are thick, maximalist and universal versus those that are thin, minimalist and local. Thick morality corresponds with abstract universal and absolute principles, which in secular discourse would be the authority of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Thin morality is a ‘reiterative’ universalism which reproduces the particular customs and traditions of a specific society ‘beyond its frontiers by successive iterations’ (12). In Busekist’s words, it ‘takes the form of a bottom-up universalism, minimal and plural, that originates in the pragmatic cohabitation or partnership between nations (12).

Ultimately, Walzer’s contributions are so perspicacious in large part due to his humility, moderation and particularism. This does not mean he rejects all deep philosophical analysis of concepts and the search for universal arguments. Rather he claims that to seek such arguments and give them a priority over existing complex and sometimes paradoxical practices demonstrates that philosophers and social critics forget the extent to which real-world constraints and complexity ought to inform their theorising. Furthermore, they ought always to remain deeply uncertain about the rightness or truth of their claims. While accepting that there are universal claims in the sense that all societies hold to values such as don’t torture, don’t kill civilians and strive for justice and fairness, this universality is almost always interpreted in different ways in different societies. So, we also need to recognise that such claims need to co-exist with irreducible value pluralism, and appreciate that human beings are prone to error due to the burdens of judgment combined with our considerable epistemological limitations. And we should also recognise that this would be problematic enough even if we could always correct for our ideological biases and characteristic hubris which appear when we are convinced that we have discovered ‘the truth’. Here is Walzer at his best, explaining the difficulties of social criticism and where so many have gone astray, and while he targets the Left it is clear he thinks this applies to those on the Right too.

Getting the world wrong is an old story. Modern society doesn’t divide into two classes as Marx predicted; nor is it a ‘mass society,’ whose members are atomised, lonely, ‘bowling alone.’ Modernity hasn’t produced the disenchantment that Weber foresaw; the triumph of science and reason over religion is still to come, if it is coming at all. Capitalism continues to survive its crises. The final victory of liberal democracy isn’t anything like final; democracy still needs advocates and fighters. All this we have to understand, and understanding requires empirical and theoretical work. But we know that this work will produce divergent analyses and fierce disagreements. We know we will be forever bereft of what leftists once called The Correct Ideological Position. It is argument itself, the ongoing analysis of where we are and what needs to be done, to which we have to commit ourselves. And that means that social criticism can’t depend on a definitive social theory. It is at least partially an independent activity. We criticize a society that we are simultaneously struggling to understand (168) (My emphasis).

We can, and almost always do, disagree on fundamental issues and so should be cognisant that any attempt to impose one correct ideological position will almost certainly result in tyranny and injustice. Susie Linfield’s recent article about the phenomenon of the progressive atrocity bears this out. So called progressives, many of whom are self-identified Leftists, commit, condone or excuse the unspeakable atrocities of Hamas on 7 October. They insist on a particular ‘understanding’ of the events in Israel on 7 October and the subsequent war, as I mentioned above, in terms of a Manichean narrative that portrays the Israelis as aggressors, occupiers and colonists, while Hamas is deemed a liberation organisation engaged in legitimate resistance. (See in Fathom, Nelson’s and Johnson’s excellent articles on this point. Here we see the serious moral collapse of a section of the Left in the same way in which pro-Stalin supporters excused and even justified the horrific crimes of the Soviet regime. The horrendous actions of those who are deemed ‘oppressed’ according to a rigid grand narrative are not only given a moral pass for their actions but are applauded for engaging in righteous resistance. It is a form of self-generated blindness that bedevils those who develop and seek to mould the world according to this grand narrative. It hampers critical thinking, adamantly rejects all feedback and develops a rigid orthodoxy which we recognise in its most stark form as a dangerously ideological cult. The refusal to acknowledge contrary arguments and claims is then motivated by the need to prevent cognitive dissonance from undermining a cherished utopian vision. For example, the fact that feminists, or gays, or anyone who claims to hold secular humanist values, supports a theocratic terrorist organisation such as Hamas is not simply a performative contradiction but deeply damaging to the very causes they claim to champion. The deep irony here is that this delusion results in behaviours which seriously harm the very groups their ideological stance is claiming to aid and emancipate.

Finally, if there is still doubt that Justice is Steady Work ought to be carefully read for its wisdom, there is another attractive aspect to it which should be mentioned. This book offers a fascinating window into the events and their impact on well renowned and respected Anglo-American political philosophers and Marxists of the second half of the 20th century. Walzer’s anecdotes about famous figures, his political concerns, his disagreements with his peers, and his considerable activism, make captivating reading in themselves. This book offers a rare form of academic autobiography, packed as it is with stories about many great academic and political figures from the 1960s onward in the USA, UK and Israel. Walzer’s engagement with these leading politicians and thinkers provides the background and motivation for his stellar contribution to the debate concerning many of the great political and philosophical issues of the last 60 years. All of this I found endlessly fascinating, and even though I have read most of Walzer’s academic opus and political articles, this book uniquely offers new material that was until now not available. It is a fascinating conversation between two political theorists which delves into that aspect of how intellectual work motivates political activism and vice versa. I conclude with Von Busekist’s comment about the nature of her dialogue with Walzer throughout the book. It accurately describes the tenor of the book, one which made reading it a very great pleasure indeed.

Our conversation has been long, rich, amicable, and personal. We disagreed here and there, but what motivated our discussions was a keen sense of humour and a profound solidarity on what really matters.