On the 120th anniversary of Theodor Herzl’s death, Fathom publishes an extract from Philip Earl Steele’s recent book On Theodor Herzl’s encounters with Zionist thought and efforts prior to his conversion in the spring of 1895. Steele finds that, contrary to near-universal assumptions over the last 125 years, Herzl was in fact well aware of Zionist efforts before 1895.

1. Introduction

This article presents not one, but a series of new discoveries that demonstrate Theodor Herzl’s real-time awareness of the Blackstone Memorial of March 1891, that boldest expression of US Christian Zionism in the 19th century, when Chicago’s William Blackstone persuaded America’s WASP elite to petition President Benjamin Harrison to convene an international conference with the purpose of establishing a Jewish state in Palestine. It also demonstrates that Herzl knew of the Memorial’s long-forgotten British ‘spin-off’ – namely, the Lovers of Zion Petition submitted to the British Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, in May that year, also in the aim of organising the Jewish resettlement of Eretz Israel.

In the literature to date, the Blackstone Memorial is described as being virtually unknown in contemporaneous Europe, and – despite its similar proposals to those of Herzl’s The Jewish State (1896) – totally unknown to Herzl himself. Thus, the findings laid out here below elevate William Blackstone all the higher in the history of 19th-century Zionism, as they do the broader Evangelical Christian component of the Zionist movement. Indeed, the words of the outstanding early American Zionists Nathan Straus and Louis Brandeis – that Blackstone was ‘the father of Zionism’[1] – now ring less like ones of mere flattery and gratitude.

The core of this article is an adapted excerpt from Steele’s latest book, which, on the power of over a dozen cases, debunks the canonical view holding that ‘In discovering Zionism, Herzl in fact reinvented the wheel … He knew nothing about his precursors’[2]. Steele’s On Theodor Herzl’s encounters with Zionist thought and efforts prior to his conversion in the spring of 1895 was published in July, 2023 by the Polish Academy of Sciences, Centre for Historical Research, and is available here in Open Access.

2. Just What is Zionism? And What is Christian Zionism?

Zionism is intrinsic to the modern era’s Jewish national revival. Over the century-plus before 1948, Zionism was focused on recreating an independent Jewish homeland, a centre, a state, in Eretz Israel. Since 1948, when David Ben-Gurion announced the birth of modern Israel – Zionism has meant the justification and protection of the right of Israelis to their state. Raison d’être.

From its beginnings in the early 19th century, the Zionist dream was fostered by Christian Evangelicalism. Indeed, Professor Anita Shapira of Tel Aviv, widely regarded as the doyen of scholars of modern Israel, writes in her marvellous synopsis Israel: A History: ‘[T]he idea of the Jews returning to their ancient homeland as the first step to world redemption seems to have originated among a specific group of evangelical English Protestants…; they passed this notion on to Jewish circles’[3].

For most of the 19th century, Zionism was known primarily as ‘Restorationism’, and this goes for both Christian and Jewish circles. After all, Vienna’s Nathan Birnbaum first coined the terms ‘Zionist’ and ‘Zionism’ not until 1890. However, as Herzl’s close ally Max Nordau stressed in 1902, ‘Zionism is a new word for a very old object’[4].

Christian Zionism rests with the belief, grounded in St. Paul’s teaching found in Romans 9-11, that God’s covenant with Israel was not supplanted by Christianity, and that – in accordance with Biblical prophecies – the Jews would one day return to their ancient homeland. And of course this grand outcome was to be fostered and supported by Christians.

Restorationist belief had accompanied the Protestant Reformation since its inception in the 16th century, particularly in its Calvinist form, which swiftly replaced Catholic saints with the Hebrew prophets and heroes of the Old Testament – i.e. the Hebrew Bible. This goes far in explaining why Hebrew names have been so popular in English-speaking countries for the past centuries – all those Christian Rachels, Ruths and Saras – Benjamins, Joshuas and Nathans. Broadly treated, Christian Zionism is most closely associated with what today we conveniently refer to as ‘Evangelical Christianity’, whose teachings would condition its adherents to esteem modern Jews as Biblical Israelites.

Nonetheless, Christian Zionism became a political objective only after the Napoleonic Wars, once Britain had become a powerful global empire possessing the means to pursue the restoration of a ‘national home for the Jewish people’ in Palestine. We then see a combination of religious faith and imperial policy on behalf of the Zionist idea that begins in the 1830s. Britain moreover was widely believed to be prophesied to play a surpassing role in this enterprise. The prophet Isaiah’s ‘ships of Tarshish’ were interpreted to be British, and that they would one day deliver ‘thy sons from afar, their silver and their gold with them’. It was in this unfolding context that Britain established a consulate in Jerusalem in 1838 and a joint Anglican-Lutheran bishopric there with Prussia in 1841, with the Christian Zionist Anthony Ashley Cooper (Lord Shaftesbury from 1851) being a moving force in each case.

3. American Christian Zionism: President, Prophet, Professor, Pastor…

Restorationism boasted adherents among American Evangelicals, as well. For example, we encounter Restorationism in the thoughts of John Adams. In 1819, the former president wrote a letter to the American diplomat Mordecai Noah, a Jew who had just published a book about his travels i.a. to the Maghreb, picturing him ‘at the head of a hundred thousand Israelites indeed as well disciplin’d as a French army—& marching with them into Judea & making a conquest of that country & restoring your nation to the dominion of it—For I really wish the Jews again in Judea an independent nation’[5].

From the early 1830s, the Mormon prophet Joseph Smith called for the Restoration of the Jews to their ancient homeland. In 1841, Smith sent an emissary, Orson Hyde, to Palestine. On the Mount of Olives in the fall of that year, Hyde prayed that God would ‘restore the kingdom unto Israel – raise up Jerusalem as its capital, and constitute her people a distinct nation and government’[6].

A few years later in 1844, a professor of Hebraic studies at New York University published The Valley of Vision; or, The Dry Bones of Israel Revived. In it, he argued that the prophecies contained in the book of Ezekiel ‘afford abundant warrant for the belief that we are now just upon the borders of […] the restoration of the Jews to Syria’[7]. Interestingly, the author of these words was… George Bush (1796-1859), and he was the brother of George W. Bush’s great-great-grandfather.

In the 1860s and 1870s, the English preacher John Nelson Darby visited America as many as seven times, promoting an eschatological vision called ‘dispensationalism’, which insisted even more stridently than before that God’s promises to the people of Israel remained in effect – and were soon to be fulfilled. Darby’s doctrines were adopted in influential Evangelical circles and by such prominent figures as James Brookes, Dwight Moody, Cyrus Scofield, and… William Blackstone. The latter’s career makes especially clear how deeply intertwined were the efforts of both Jews and Christians to restore the Jews to Israel.

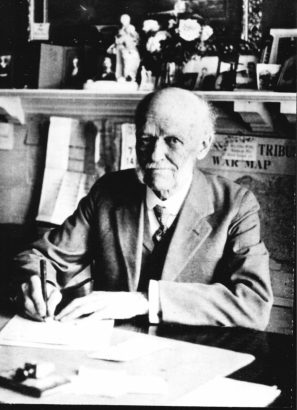

4. The Blackstone Memorial of 1891

On 24 & 25 November, 1890, the ‘Conference on the Past, Present, and Future of Israel’ was held in Chicago at the First Methodist Episcopal Church[8]. Attended by leading Christians and Jews, the gathering was organised by William Eugene Blackstone (1841-1935), a lay Christian Evangelical who had become absorbed with Biblical prophecy under the influence of John Nelson Darby[9]. In 1878 Blackstone’s eschatological work Jesus is coming was published. Within twenty years the volume had sold over one-million copies in tens of languages[10].

In 1888 Blackstone sailed to England to attend a missionary conference, after which he and his daughter Flora journeyed to the Holy Land, where they travelled about on horseback, visiting not only the Christian pilgrimage sites[11], but also many of the new moshavot (settlements) established earlier in the decade during the First Aliyah[12]. Blackstone’s encounters with Jewish pioneers and refugees along the way and back strengthened the shift within him toward an active messianism akin to that of the Jewish founders of religious Zionism, rabbi Tsevi Hirsch Kalischer of Toruń, Poland most prominent among them[13]. Hence, once back in Chicago in 1889, Blackstone began to reach out to both Jewish and Christian leaders and was soon laying plans for the famous conference. Amongst the several rabbis it featured was the prime mover behind Chicago’s Reform Jewish Sinai Temple, Bernhard Felsenthal[14], who at the opening session delivered the bluntly entitled address, ‘Why Israelites do not accept Jesus as their Messiah’[15].

Buoyed by the participants’ broad assent for restorationist aims and their unanimous concern for the fate of Russia’s persecuted Jews, Blackstone decided to press the matter with the American administration. He therefore drafted a petition (the ‘Memorial’) to President Benjamin Harrison seeking the Jews’ restoration to the Land of Israel. As often repeated, the 413 signatories comprised a list of Who’s Who in America, and this was no doubt central to the fact that the Chicagoan was welcomed at the White House by the President and Secretary of State James Blaine on 5 March, 1891. For the VIPs who had endorsed the Memorial included some 200 religious leaders, Christian and Jewish[16], along with leading politicians, businessmen, and media titans. ‘Blackstone obtained the signatures of […] fifty-three newspaper editors, seven college presidents, the industrialists Rockefeller, Morgan, McCormick, Armour, Dodge and Scribner; the Chief Justice and twenty two federal and state jurists, the Speaker of the House and eight other members of Congress, the Governors of Massachusetts, New York and Illinois, and the Mayors of New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore’[17]. The specific request of the Blackstone Memorial was that the US organise an international conference devoted to establishing a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In the words of the Memorial itself:

Why not give Palestine back to them again? According to God’s distribution of nations it is their home; an inalienable possession from which they were expelled by force… Why shall not the powers which under the treaty of Berlin, in 1878, gave Bulgaria to the Bulgarians and Servia to the Servians now give Palestine back to the Jews? These provinces, as well as Roumania, Montenegro, and Greece were wrested from the Turks and given to their natural owners. Does not Palestine as rightfully belong to the Jews?[18]

Regarding Jewish matters, the Blackstone Memorial caused the greatest stir in all of 19th-century America, excelling even Herzl’s Der Judenstaat and the First Zionist Congress[19]. Concerning just the still nascent Jewish population in 1891[20], the Memorial garnered the support of but a minority of rabbis and other Jewish leaders, and thus the tiny American Jewish press was markedly reluctant toward the Memorial. After all, American Jews did not begin to meaningfully back Zionism until World War Two. The Hebrew-language weekly Ha-Pisgah (‘the summit’), edited by Wolf Schur and read in Hovevei Zion milieux on both sides of the Atlantic, was an exception in having printed a highly favourable article on the Memorial shortly after its submission at the White House[21].

As we know, the US did not manage to achieve the goals of the Blackstone Memorial, though concrete steps were taken. On 6 April, 1891 the US ambassador to Russia, Charles Emory Smith, spoke with the Tsar’s minister for foreign affairs, Nikolay de Giers, who responded positively to the idea of an international conference on ‘restoring Palestine’ to the Jews[22]. Harrison and Blaine subsequently had the consul in Jerusalem, Selah Merrill, file a report on the chances of persuading the Sultan to agree to opening Palestine for Jewish settlement – and Merrill could only scoff[23].

Concerning William Blackstone’s subsequent restorationist career, the literature purports that soon following the First Zionist Congress six years later, he marked key passages of prophecy in a Hebrew Bible and posted it to Herzl, and that somewhere in the wake of Herzl’s reburial in Yerushalayim in 1949, the Bible was on display at Mount Herzl[24]. This story has yet to be substantiated, however, and may well be a myth – as I shall point out below. Thereafter we learn that on 26 May, 1916 an updated version of the Memorial was adopted by the Presbyterian church at its annual General Assembly and then tendered to President Woodrow Wilson (the son of a Presbyterian minister), who was thereby encouraged to approve a final draft of Great Britain’s Balfour Declaration in October, 1917[25]. Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, who was co-ordinating efforts behind the scenes to secure Wilson’s acceptance of the British War Cabinet’s plan, later recalled the President exclaiming, ‘To think that I, the son of the manse, should be able to help restore the Holy Land to its people’[26].

Beyond that, the Blackstone Memorial has been rightly applauded as the boldest testimony to WASP America’s commitment to Jewish nationhood, coming as it did before the US Jewish population was sizeable, influential, and pro-Zionist. About the standing of William Blackstone the man, his friend Louis Brandeis – the US Supreme Court Justice and Zionist leader whose name is enshrined at Brandeis University in Massachusetts – agreed with Nathan Straus that Blackstone was ‘the father of Zionism’[27].

Nonetheless, the Blackstone Memorial is described as ‘hardly known in Europe’[28], the literature’s universal conclusion being that there is no evidence Theodor Herzl was aware of it.

5. The Blackstone Memorial’s coverage in the European press

In fact, the Blackstone Memorial made its presence known across the Atlantic in three significant ways, each of which leads to Theodor Herzl ante 1895, the year he underwent his Zionist conversion.

First, beginning in mid-March, 1891 the Memorial was widely covered throughout the continent, one example being the Allgemeine Zeitung, the leading German daily for much of the 19th century[29]. In the UK that additionally included articles on both the November, 1890 conference in Chicago and the period when signatures were being gathered[30]. ‘Gentile’ newspapers in Poland also reported on the Memorial – Gazeta Polska (6 May, 1891), Tygodnik Mód i Powieści (16 May, 1891), Głos (18 May, 1891) – as did the assimilationist, Polish-language, Izraelita, which on 8 May, 1891 shared: ‘The London dailies are offering a curiosity – to wit, that the President of the United States is seriously intending to propose to the Powers that they convene an international conference in order to weigh the question of creating a sovereign Jewish state in Palestine. Si non e vero…’[31].

One of the first German-language newspapers to cover the Blackstone Memorial was the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung. Herzl deemed his literary career to have begun with that Viennese paper when he won 1st prize in its competition for best feuilleton in May, 1885. Over the next 5 years he wrote for the WAZ in various capacities, and continued reading it thereafter. On 22 March, 1891 the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung ran an approximately 650-word piece titled, ‘The Re-establishment of the Kingdom of Israel’[32]. It begins with an account of a recent local lecture on scriptural prophecies that concluded with the topic of a restored Israel. Fascinatingly, the lecturer is none other than Rev. William Hechler, who five years later was to become vitally important to Herzl. The article then pivots to the United States, and gives this report on the Blackstone Memorial:

Mr. William E. Blackstone of Chicago … appeared [in Washington DC] in the company of Secretary of State Blaine, to present to President Harrison a memorial signed by distinguished businessmen, newspaper editors, politicians, etc. from all parts of the country. The document requested that the government of the United States exert its influence with the governments of Europe on behalf of convening an international conference at which steps shall be taken to give the children of Israel the Promised Land, especially in view of the persecutions of the Jews in Russia. As Mr. Blackstone explained, this plan might well be carried out if Jewish capitalists paid a part of the Turkish national debt in exchange for the territory to be ceded, which could be under the control of the treaty powers, and thus made the necessary money immediately available to the Turkish government, which is in dire financial straits[33]. Since the United States is on good terms with Russia and is not directly interested in solving the Eastern question, that government is optimally suited to bring the matter to a head and bring about a favourable decision. Mr. Harrison listened attentively to the remarks of [Blackstone] and promised to consider the proposal …

Like the UK papers, Nathan Birnbaum’s Selbst-Emancipation in Vienna drew attention in mid-February, 1891 to the soliciting of signatures for the petition to the US president[34], and six weeks later ran an article on the submission of the Blackstone Memorial at the White House. Entitled, ‘The Americans and the colonisation of Palestine’, here is its salient portion:

The Anglo-Saxon race is more and more proving to be the one called upon to perform an outstanding role in the history of the revival of the Jewish folk in its ancestral land… As the strictly Zionist, Hebrew weekly Ha-Pisgah in Baltimore reports, Mr. William Blakestone [sic], accompanied by Presidential Minister [sic] Blaine, was received by the President of the United States at his palace in Washington on the 5th of this month (March), and presented a petition in the matter of the Russian Jews. Mr. Blakestone explained to the President, Mr. Harrison, that this petition was the execution of a resolution passed by Christian and Jewish men from all over America who had met in Chicago to discuss measures to help the Russian Jews, and that it did not contain any censure against Russia, but rather dealt with the question of how the Jews could be peacefully restored to their ancestral land. Mr. Blakestone brought persuasive evidence to the President that Palestine was a fertile land suitable for farming and trade, especially if it fell to skilful hands, all the more so as the Jerusalem-Jaffa railway would soon be completed and would later extend to Damascus and Palmyra and even farther to the banks of the Euphrates… The President of the United States listened kindly to Mr. Blakestone’s remarks and assured him he would turn his attention to the petition and do his utmost in this matter… In its appraisal of this event, Ha-Pisgah quite rightly observes that, although in itself [the Memorial] is unlikely to produce any tangible result, it is still capable of awakening the most beautiful hopes in us. For it is now certain that the recognition of the only correct, Zionist solution to the Jewish question is beginning to take hold among Christians.[35]

Among the very many other examples of the Blackstone Memorial being covered in the German press is the page 1 story in Hamburg’s important daily newspaper, Altonaer Nachrichten of 6 May, 1891.

Having returned home on 1 March from nearly three weeks of travel about northern Italy and the French Riviera, Herzl throughout this period was in Vienna, where he had ready access to accounts of the plight of Russian Jews fleeing persecution and often dreaming of life in Eretz Israel – as he did to the US initiative to help them do so. This is likely reflected in the fact that Blackstone’s proposal for the Jews to offer the Sultan assistance with financing the Ottoman empire’s debt became Herzl’s own. He tabled the idea in Der Judenstaat in the subsection ‘Palestine or Argentina?’: ‘Palestine is our ever-memorable historic home. The very name of Palestine would attract our people with a force of marvellous potency. If His Majesty the Sultan were to give us Palestine, we could in return undertake to regulate the whole finances of Turkey’[36].

6. The Blackstone Memorial’s British Child – The Lovers of Zion Petition

Secondly, that very spring the Chicagoan’s Memorial inspired an analogous petition in Great Britain – namely, the Lovers of Zion Petition[37], sponsored by Samuel Montagu, Albert Goldsmid and the leaders of Hovevei Zion (the Lovers of Zion) in the UK[38]. They drew upon the American endeavour known to them via articles in The Jewish Chronicle and Hovevei Zion channels (including Ha-Pisgah’s endorsement of the Blackstone Memorial)[39] when resolving to respond to Russia’s renewed persecution of Jews from late April that same year[40]. Thus, on 23 May, 1891 amidst a gathering of some 4,000 people – both Jews and ‘a large proportion’ of Christians – at the Great Assembly Hall, Mile End in support of the Russian Jews, Montagu and Goldsmid with the help of rabbi Simeon Singer drafted a petition and amassed a list of signatures running 12 yards in length[41]. The Lovers of Zion Petition was then submitted on behalf of Hovevei Zion to Prime Minister Salisbury by Baron Nathan Rothschild[42]. Released to the press late that month, the Petition beseeched Lord Salisbury to make overtures to both the Tsar and the Sultan for the sake of the Jewish refugees wishing to begin new lives in Palestine[43]: ‘they love the very stones and favour the dust thereof [Psalms 102:14] and they would deem themselves blessed indeed if they were permitted to till the sacred soil’[44].

Although today the Lovers of Zion Petition has sunk into oblivion, at the time it was much more extensively covered in the European press than the Blackstone Memorial, and there were scores of follow-up stories on its progress. In the German-world, articles about the Petition began appearing in late May from Hamburg to the southern Tyrols and all points ‘twixt and ‘tween – including Herzl’s ‘own’ newspapers, the Berliner Tageblatt, Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, and Neue Freie Presse[45].

One example spreads over pages 1 and 2 of the 31 May, 1891 edition of the Neue Freie Presse. It contains the full translation of a letter to Samuel Montagu from William Gladstone, then between his 3rd and 4th terms as Prime Minister. Montagu had enlisted Gladstone’s help in the efforts surrounding the Lovers of Zion Petition, believing him, albeit out of office, to have the ear of the Tsar. This Gladstone denied, though he did stress to Montagu his approval of Jewish settlement in Palestine: ‘I regard with warm and friendly interest the plan of a significant migration of the Jews to Palestine, and will be very happy if the Sultan supports such migration’[46].

On 11 June the evening edition of the NFP reported: ‘The Marquis of Salisbury sent a letter to Baron Rothschild in response to the petition addressed to him, requesting the backing of the English government in order to obtain permission from the Sultan for the settlement of Russian Jews in Palestine. Salisbury states in this letter that he will contact the English ambassador in Constantinople asking whether the intervention of the English government would help to attain this purpose; if the answer is affirmative, the ambassador will convey the matter to the Sultan’[47]. This story was repeated by Herzl’s former newspaper, the Berliner Tageblatt, that very evening[48] – and by the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung the next morning[49]. Moreover, on the following day the WAZ ran: ‘An appeal for the establishment of Jewish colonies in Palestine’, signed by Nathan Birnbaum and Moritz Schnirer of the famous Viennese Zionist group Kadimah, Haham Moses D. Alkalay, and the publisher Chaim David Lippe[50], among other men representing Vienna’s ‘Association for the Support of the Colonisation of Palestine’. The Association’s appeal, intended to capitalise on the current uproar, reads in part:

Palestine-Syria with its fertile valleys, from which delicious wine and the most splendid southern fruits hail, with its high plateaus rich in pasture and grain (Syria, the granary of Asia!) with its mountains and lakes rich in minerals, is, with its present extremely sparse population, the most amenable area for millions of our persecuted co-religionists … and it is, of course, that country to which the majority of Russian Jews feel drawn in pious reverence and to which they would most like to be sent…

At the present time a network of associations supporting this colonisation, with many tens of thousands of members, is spreading all over the globe, and in England and North America the most distinguished and best, both of Christian and Jewish confession, are extremely sympathetic or directly supportive of the enterprise. Let us mention first of all Gladstone and the President of the United States of North America, Harrison, then the Duke of Westminster, Earl of Aberdeen, Lieutenant Colonel Albert Goldsmid… Samuel Montagu, etc…

Fellow Israelites in Austria! Do not lag behind your fellow believers in other countries any longer! Join in the great humanitarian endeavour of resettling our oppressed brothers in Palestine and Syria – an enterprise whose success is beyond question! … Brothers! Do not hesitate any longer. Do your duties as men and Israelites![51]

The next day (13 June) the Berliner Tageblatt ran a lengthy piece on pp. 1-2 entitled ‘The emigration of the Russian Jews’ that included the destination of Palestine[52]. Follow-up stories came i.a., on 24 June and 3 July.

Back to the Neue Freie Presse, in the 14 June edition we read: ‘As far as the colonisation of Palestine is concerned, the above-mentioned association [Hovevei Zion], as reported by telegraph, has applied to Lord Salisbury for the assistance of the English government to obtain permission from the Sultan for the settlement of Russian and Polish Jews in Palestine. Lord Salisbury has sent word through his private secretary [Philip] Currie that he has informed the Queen’s ambassador to the Porte on the issue of whether the intervention of the English Government might contribute to the achievement of the objective in question. Should this be the case, Sir William White would be authorised to bring the matter to the attention of the Sultan’[53].

Among the deluge of articles on the Lovers of Zion Petition, numerous editions of Herzl’s Neue Freie Presse in this period also provided reports of Russian Jews emigrating to Palestine in ways unrelated to the Petition[54]. One is therefore hard-pressed to imagine how the journalist Herzl could have failed to notice the multi-pronged campaigns for the Jewish resettlement of Palestine – though explanations can be made.

The first is by no means indulgent: when Theodor’s dearest friend Heinrich Kana took his own life in early February that year, Herzl was grief-stricken and at once fled Vienna alone to the Piedmont. Battling suicidal thoughts over his three weeks of desultory wandering, Herzl wrote life-line letters to his mother and father nearly every single day – most of them begin ‘Meine vielgeliebten Eltern’, My much-beloved parents. Back home from March, Herzl was despairing for his marriage. By May the 31-year-old was preoccupied with preparations to divorce Julie; he remained present for his son Hans’ birth on 10 June, but then left Vienna on 28 June with his mother, his lawyers being instructed to commence dissolution proceedings[55]. Jeanette Herzl returned home to her husband Jakob a fortnight later; their son slowly picked his way westward across Occitania, haunted by Heinrich’s ghost and wracked by guilt over the pain and shame his divorce would cause.

It is also true that Herzl’s full-time position with the Neue Freie Presse began not until early October 1891 when he cut short his working vacation in the Basque Land and raced to Paris to become the paper’s correspondent[56]. Even so, he had been steadily writing feuilletons for the NFP as a freelance contributor, and if only for that reason was regularly turning its pages. His daily habit, after all, was to visit ‘with bureaucratic punctuality’ a favourite café and sit at a marble reading table, where his voracious perusal of ‘the dailies and the weeklies, the comic sheets and the professional magazines … never consumed less than an hour and a half’[57]. In sum, both the Blackstone Memorial and its British scion, the Lovers of Zion Petition, remained staple news across Europe for long weeks during the spring and early summer of 1891. Somewhere out in the middle of the Aegean or Black Sea that May, the story of the Lovers of Zion Petition even managed to reach Ahad Ha’am as he sailed from Jaffa to Odessa. Indeed, while aboard ship he described the Petition in his famous essay, ‘Truth from Eretz Israel’, published as a series of pieces in HaMelitz between 19 and 30 June, 1891[58].

Hence no valid doubts can be held but that Herzl, despite his anguish, was well aware of the two diplomatic initiatives toward fostering a Jewish return to Palestine. This is still further to be excluded as Herzl had personal knowledge of the broader crisis: Theodor’s sole remaining friend, Oswald Boxer, informed him that spring about his involvement on behalf of the Jewish refugees in Berlin’s Deutsches Centralkomitee für die Russischen Juden, and once in Brazil that summer he was writing to Theodor about his progress in conceiving a Jewish colony there[59].

The above events have an interesting sequel, for in November 1895 Herzl was in Britain, where he had intimate conversations with three of the principle actors behind the Lovers of Zion Petition – namely, Samuel Montagu, Albert Goldsmid and Rev. Simeon Singer[60]. It is hardly possible that the men neglected to recall to Herzl their involvement with the Petition – all the more so, as Montagu, for one, is known to have publicly boasted his role in the undertaking[61]. Nonetheless, Herzl preserved no account in his Diaries of such reminiscing, and this should be reckoned characteristic. He did, however, allude to the Petition shortly thereafter – namely, in an entry from 14 May, 1896: ‘I am answering [the letter from Reverend] Singer by informing him for Montagu’s benefit that I do not wish to address an ‘appeal’ to the Sultan (which would be a typically English notion), but will negotiate with him secretly and possibly summon Montagu to Constantinople so that he may support me’[62].

7. The Blackstone Memorial inspires the writing of a Zionist utopian novel

The third European legacy of the Blackstone Memorial is that it inspired a German-language Zionist utopian novel that opens with a scene of homage paid to the imagined Israel’s three great founders – none other than William Blackstone, Benjamin Harrison, and James Blaine. Moreover, this was a novel that Theodor Herzl knew.

In 1893, two years after the Blackstone Memorial was submitted at the White House, one Max Osterberg-Verakoff published Das Reich Judäa im Jahre 6000 (2241 Christlicher Zeitrechnung)[63], or: The Jewish Kingdom in the year 6000 (2241 AD). Miriam Eliav-Feldon, in her analysis of the Zionist utopia genre, describes its beginning as follows: ‘After the expulsion of Jews from Moscow in 1891, a compassionate American evangelist, William Blackstone, had presented a memorandum to President Harrison urging the restoration of the Land of Israel to the Jews in order to rescue them from persecution in Tsarist Russia. Blackstone’s petition becomes, in the story, the basis for the initiative taken by the United States to help create the Kingdom of Judah. The book begins with a ceremonial unveiling of a commemorative statue to Blackstone, President Harrison, and his Secretary of State James Blaine’[64].

Herzl ostensibly learned about Osterberg-Verakoff’s Zionist utopia not until October, 1899. That, at least, is when he drafted a kind note on Die Welt letterhead to Osterberg-Verakoff praising the novel and asking its author why he had not joined the Zionist movement. Herzl also offered that he himself had started drafting a ‘zionistischen Zukunftsromans’ (a Zionist future-fantasy), whereby he is referring to his utopian novel Altneuland, which came out in October, 1902. He closed with the (unfulfilled) promise that he would take the opportunity in the novel itself or in its epilogue to recognize Osterberg-Verakoff’s work, as well as the kindred novels David Alroy and Daniel Deronda[65]. Once again therefore do we note the puzzling pattern of Herzl ever as a Johnny-come-lately to Zionist ideas – along with his pronounced reluctance to cite his forerunners. And of course the latter casts doubt on the former.

8. Herzl’s post-1895 contact with William Blackstone

There is also a fourth hitherto unknown connection between Blackstone and Herzl, although this one falls after Herzl’s conversion to Zionism in the spring of 1895. Namely, I have discovered that, following the First Zionist Congress, Blackstone sent Herzl a four-language version of his article entitled ‘Jerusalem’, originally published – as Paul W. Rood kindly informed me – in his quarterly The Jewish Era (vol. 1, no. 3, July 1892, Chicago, pp. 67-71). Herzl passed the brochure Jerusalem on to the Zionist weekly he had created, Die Welt, which on 26 Nov., 1897 printed at the bottom of its last page (16) a brief review. Under the heading ‘Bücherwelt’ (Book World), it reads thus in translation:

William E. Blackstone. ‘Jerusalem’. Oak Park, Illinois. 22 pp. (Hebrew, Yiddish, Spanish, English) – This little booklet, published simultaneously in four languages, takes up the cudgels for Zionism. In clear, colloquial language, it dissects the essence of Zionism, responding deftly to the various accusations, such as the non-existence of a Jewish nation, the barrenness of Palestine, and the like. The work is especially valuable, however, because of the use of quotations from the writings of the prophets Jeremiah, Ezekiel, etc., which contain a promise of the real and not merely symbolic return. Certain rabbis might even get to know the prophets from these writings. And this was sweetened for them, as Mr Blackstone (132 S. Oak Park, Illinois) is even prepared, in the interest of disseminating the booklet’s message, to send it free of charge to anyone who wishes it.

This in all likelihood is the basis of the long-rumoured Old Testament with specially marked prophesies on Israel’s restoration, claimed to have been sent by Blackstone to Herzl, and subsequently included in an exhibit on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem before mysteriously disappearing. Thanks again to the help of Paul W. Rood, I have learned of an early version of this story by one Daniel Fuchs[66]. More recent accounts are markedly inflated[67].

Indeed, it now seems doubtful that there ever was any such Old Testament – nor has any evidence come to light that Blackstone’s Jerusalem was ever on display on Mount Herzl[68].

9. The significance of the Herzl/Blackstone connection

In conclusion, William Blackstone’s impact on Theodor Herzl is one of the many important cases showing that 19th-century Jewish and Christian Zionisms were inextricably linked. Moreover, for Jews and Christians alike, Zionism arose on the fertile basis of religious, especially messianic thinking that – in interpreting the early-19th century’s promising signs, seeing in them the finger of God, anticipating the imminent fulfilment of prophecy – made the shift from passive longing to ‘active messianism’. Whereas Zionism among the Jews was swifter to embrace approaches that were no longer strictly religious (Leon Pinsker and Theodor Herzl being outstanding examples), Christian Zionism remained starkly so throughout the 19th-century: from Robert Haldane, Charlotte Elizabeth Tonna, and Lord Shaftesbury – to Henry Dunant, Rev. William Hechler, and the Chicagoan William Blackstone. Active messianists, all – ones who discerned the dawning of a new age in a way entirely kindred to the visions of rabbis Yehuda Alkalai and Tsevi Hirsch Kalischer, rabbis Samuel Mohilever and Yitshak Reines, and rabbis Kook, father and son.

Naturally, Christian Zionism remains strictly religious to this day. And as Israeli and other Jewish leaders and pro-Israeli activists have long known, this is by no means problematic. On the contrary, Christian-Jewish co-operation and cross-pollination were a key ingredient to Zionism’s flowering – and they will remain relevant to Zionism’s ongoing growth in the 21st century.

[1] Jonathan Moorhead, ‘The Father of Zionism: William E. Blackstone?’, Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 53/4, Dec. 2010, pp. 787-800; see pp. 796-97

[2] Ernst Pawel, The Labyrinth of Exile: A Life of Theodor Herzl, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 1989, pp. 214-215.

[3] Anita Shapira, Israel: A History, Brandeis University, 2012, p. 15

[4] Max Nordau, ‘Zionism’, in The International Quarterly, vol. VI, Sept-Dec. 1902, Burlington, Vermont, pp. 127-139 – quote on p. 127

[5] https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-7097 Accessed 7 June, 2024

[6] https://www.vibrationdata.com/Orson_Hyde.htm Accessed 7 June, 2024

[7] George Bush, The Valley of Vision; or The Dry Bones of Israel Revived, Saxon & Miles, New York, 1844, p. iv

[8] For the conference program, its minutes, and papers, see Jew and Gentile, Being a Report of a Conference of Israelites and Gentiles regarding their Mutual Relations and Welfare, Bloch Publishing, Cincinnati, 1890

[9] For fuller accounts of William Blackstone and his Memorial, see above all: 1) Yaakov Ariel, ‘An American Initiative for a Jewish State: William Blackstone and the Petition of 1891’, Studies in Zionism, vol. 10, no. 2, 1989, pp. 125-137; 2) Jonathan Moorhead, ‘The Father of Zionism: William E. Blackstone?’, Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 53/4, Dec. 2010, pp. 787-800; 3) Paul. W. Rood, ‘William E. Blackstone (1841-1935): Zionism’s Greatest Ally Outside of its Own Ranks’, Western States Jewish History 48,2 2016, pp. 49-69

[10] William E. Blackstone, Jesus is Coming, 2nd ed., Fleming H. Revell Co., New York/Chicago/London/Edinburgh, 1898, frontispiece

[11] Bertha Spafford Vester, Our Jerusalem: An American Family in the Holy City, 1881-1949, Doubleday & Co., Garden City N.Y., 1950, pp. 157-158

[12] Yaakov Ariel, op. cit., p. 130

[13] Jody Myers, Seeking Zion: Modernity and Messianic Activism in the Writings of Tsevi Hirsch Kalischer, The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, Oxford, 2003

[14] Leon A. Jick, ‘Bernhard Felsenthal: The Zionization of a Radical Reform Rabbi’, Jewish Political Studies Review, 9: 1-2 (Spring 1997), pp. 5-14

[15] Jew and Gentile, op. cit., pp. 14-19

[16] Among the latter signatories is dr. Henry (Haim) Pereira Mendes (1852-1937), chief rabbi of Shearith Israel in Manhattan, North America’s oldest synagogue. Six years later in 1897, after having met Theodor Herzl in London via the agency of Haham Moses Gaster, Rev. Mendes founded what soon became the Federation of American Zionists – see David de Sola Pool, ‘Henry Pereira Mendes’, The American Jewish Yearbook, vol. 40, American Jewish Committee, 1939/5699, p. 46; and ‘Born a Rabbi: H.P. Mendes Marks 60th Birthday in Pulpit’, Jewish Daily Bulletin, 24 May, 1934, p. 2. In 1897-98 Mendes published 3 articles on Zionism in The North American Review (see the issues of Oct. 1897, Aug. 1898, and Nov. 1898).

[17] Paul W. Rood, ‘Blackstone and the Rabbis: The Story of Dialogue and Cooperation between a Christian Evangelist and Two Eminent American Rabbis concerning the Future of Israel’, Blackstone Center Series, 2020, p. 5

[18] The full document is available at the Billy Graham Center Archives, Wheaton: https://www2.wheaton.edu/bgc/archives/docs/BlackstoneMemorial/1891A.htm [accessed Feb. 25, 2023]

[19] Marnin Feinstein, ‘The Blackstone Memorial’ in American Zionism, 1884–1904, Herzl Press, New York 1965. p. 56

[20] The US’s Jewish population was approx. 400,000 at the time of the Blackstone Memorial (general pop. ~63 million). It swelled nearly 4-fold to 1.5 million by 1905 (general pop. ~84 million), then doubled to 3 million by 1914 (general pop. ~98 million). See Samson D. Oppenheim, ‘The Jewish Population of the United States’, in American Jewish Year Book 5679, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1918, p. 31

[21] Bar Abi, ‘Messiah’s Trumpet’, Ha-Pisgah, 13 March, 1891 – a translation of which was published in: The Peculiar People, vol. IV, Alfred Center, NY, April 1891, pp. 22-24

[22] See Cyrus Adler and Aaron M. Margalith, With firmness in the right: American Diplomatic Action Affecting Jews, 1840-1945, The American Jewish Committee, New York, 1946, p. 225. As the authors note, this dispatch is not found in the official Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States for 1891, but rather in Dispatches, Russia, Vol. 42 No. 87, The National Archives, WA DC.

[23] See Shalom Goldman, ‘The Holy Land Appropriated: The Careers of Selah Merrill, Nineteenth Century Christian Hebraist, Palestine Explorer, and U.S. Consul in Jerusalem’, American Jewish History, vol. 85, No. 2 (June 1997), pp. 151-172

[24] See Peter Grose, Israel in the Mind of America, Schocken Books, New York, 1984, p. 37; Moorhead, op. cit. p. 795

[25] Yaakov Ariel, ‘A Neglected Chapter in the History of Christian Zionism in America: William E. Blackstone and the Petition of 1916’, in Jews and Messianism in the Modern Era: Metaphor and Meaning, ed. Jonathan Frankel, Oxford University Press, New York/Oxford, 1991, pp. 68-85; and Richard Ned Lebow, ‘Woodrow Wilson and the Balfour Declaration’, The Journal of Modern History, vol. 40, no. 4 (Dec., 1968), The University of Chicago Press, pp. 501-523

[26] Stephen S. Wise, Challenging Years: the autobiography of Stephen Wise, Putnam’s Sons, NY, 1949, pp. 186-187

[27] Moorhead, op. cit., p. 796-97

[28] Ariel, ‘An American Initiative for a Jewish State…’, op. cit., p. 134

[29] See Allgemeine Zeitung, 2 April, 1891, p. 3; 13 April, p. 6; 19 April, p. 8

[30] I have found four such articles on the November conference, and a dozen on the gathering of signatures.

[31] Izraelita, 8 May, 1891 (nr. 18), p. 12

[32] ‘Die Wiederaufrichten des Reiches Israel’, pp. 3-4

[33] In the words of Blackstone Memorial itself: ‘Whatever vested rights by possession may have accrued to Turkey can easily be compensated, possibly by the Jews assuming an equitable portion of the national debt’ – see the full document, footnote 148

[34] Selbst-Emancipation, 16 February, 1891, p. 7

[35] Ibidem, 1 April, 1891, pp. 3-4

[36] Cf. CD vol 1, p. 338 (25 April, 1896); and CD vol 2, pp. 500-501 (1 Dec., 1896)

[37] My own term.

[38] For both the background story and the full text of the Petition, see ‘The Colonization of Palestine: Important meeting – a Petition to the British Government’, The Jewish Chronicle, 29 May, 1891, p. 8

[39] News of signatures being gathered for the Blackstone Memorial, along with its purpose, was reported by The Jewish Chronicle, 6 Feb., 1891, p. 14 – and news of the Memorial’s presentation at the White House, including excerpts from the text, was covered therein on 24 April, 1891, p. 11. Ha-Pisgah, in turn, was then being distributed in England – see Jacob Kabakoff, ‘The Role of Wolf Schur as Hebraist and Zionist’, in: Essays in American Jewish History, The American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, 1958, pp. 425-456 – and it had reached Vienna in late March (see the above fragment of the 1 April, 1891 article in Selbst-Emancipation).

[40] Daniel Gutwein, ‘The Politics of Jewish Solidarity: Anglo-Jewish Diplomacy and the Moscow Expulsion of April 1891’, Jewish History, vol. 5, no. 2, Fall, 1991, pp. 23-45

[41] Moshe Perlman, ‘The British Embassy in St. Petersburg on Russian Jewry, 1890-92’, Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, Vol. 48 (1981), p. 308

[42] Emil Lehman, The Tents of Michael: The Life and Times of Colonel Albert Williamson Goldsmid, University of America Press, Lanham/New York/London, 1996, pp. 109-111. Rev. Singer additionally translated the Petition into Hebrew; and ‘The Colonization of Palestine by Jews’, Pall Mall Gazette, 25 May, 1891, p. 6

[43] See Cecil Bloom, op. cit., pp. 24-25

[44] See full text, op. cit.

[45] Among the host of other German-language newspapers that reported on the Lovers of Zion Petition are: Hamburger Anzeiger, Hamburger Nachrichten, Berliner Börsenzeitung, Volkszeitung, and Meraner Zeitung. Among the Dutch newspapers are: De Tijd, De Standard, Rotterdamsch Nieuwsblad, Tilburgsche Courant – among the French: Le Temps, L’Univers, Le Matin, La Croix.

[46] Both letters – Montagu’s and Gladstone’s – were published in full two days prior in The Jewish Chronicle on 29 May, 1891, p. 7., as was Gladstone’s in St. James’s Gazette (29 May, 1891, p. 11), where the former/future PM’s remark in the original is: ‘I view with warm and friendly interest any plan for the large introduction of Jews into Palestine, and shall be very glad if the Sultan gives his support to such a measure’.

[47] Neue Freie Presse, 11 June, 1891, Abendblatt p. 3. Cf., ‘Lord Salisbury and the Russian Jews’, St. James’s Gazette, 11 June, 1891, p. 12

[48] Berliner Tageblatt (Abend Ausgabe), 11 June, 1891, p. 2. Herzl worked for the paper from late 1886 to late 1888 and thereafter maintained regular contact with its editor-in-chief, Arthur Levysohn.

[49] Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 12 June, 1891, p. 4

[50] Rabbi Moses ben David Alkalay of Belgrade is a relative of the early Zionist rabbi Yehuda Alkalai of Zemun (Semlin), Serbia (see Conclusion). Chaim David Lippe, in turn, is the brother of Karpel Lippe, who figures earlier in this text.

[51] Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, 13 June, 1891, p. 2

[52] See Abend Ausgabe, ‘Die auswanderung der russischen juden’.

[53] Neue Freie Presse, 14 June, 1891, p. 4; see follow-up 25 June, 1891, reporting on difficulties with the Porte. The NEP’s article from 14 June was found in The Jewish Chronicle on 12 June, p. 9

[54] See ibid 16 & 18 June, 1891

[55] See Ernst Pawel, op. cit., pp. 136-39

[56] Ironically, on Herzl’s first full day in Paris, the Neue Freie Presse ran a story that included the Zionist idea. The piece is on the celebrations in Paris of the 100th anniversary of Jewish emancipation. There is no byline, but it was probably written by Max Nordau. It declares the Jews to be Frenchmen enjoying all legal obligations and privileges, and concludes with a joke from the 19th-cent. repertoire: ‘with the exception of the Jews in the East, who dream of a New Jerusalem, no Israelite longs for Palestine. And thus a witty [Western] Jew, when told about the re-establishment of the Kingdom of Judah, stated »As far as I am concerned, I would not be at all chagrined by this, provided that I am appointed royal ambassador to Paris«’ – Neue Freie Presse, 7 Oct., 1891, p. 5

[57] Thus in Herzl’s novel Old New Land do we encounter Dr. Friedrich Loewenberg, who Herzl doesn’t even begin to conceal is he himself. He goes so far as to assign to Loewenberg his own closest friends by their true names, i.e., the now deceased Heinrich Kana and Oswald Boxer: ‘Heinrich had written him just before sending a bullet into his temple … Oswald went to Brazil to help in founding a Jewish labor settlement, and there succumbed to the yellow fever’ – see Theodor Herzl, Old New Land, trans. Lotta Levensohn, Markus Weiner Publishing and The Herzl Press, New York, 1987, p. 3

[58] See Alan Dowty, Ahad Ha’am and Asher Ginzberg, ‘Much Ado about Little: Ahad Ha’am’s »Truth from Eretz Yisrael«, Zionism, and the Arabs’, Israel Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Fall, 2000), pp. 154-181

[59] On 13 June, 1891 Herzl wrote a lengthy letter to Boxer that begins with reference to a letter he had just received from Oswald – see Briefe und Tagebücher, Erster Band op. cit. no. 508, pp. 447-450. See also Herzl’s obituary of his friend in the Neue Freie Presse, 4 February, 1892, p. 1 of Abendblatt, where he refers to their ongoing correspondence during Oswald’s time in Brazil and quotes passages from Oswald’s final letter to him.

[60] See CD vol. 1, pp. 277 & 280 concerning Montagu; ibidem pp. 281-283 concerning Goldsmid; and ibid pp. 277-278, 280, 283-284 concerning Singer.

[61] See Bloom, op. cit., p. 26

[62] CD vol. 1, p. 350

[63] Max Osterberg-Verakoff, Das Reich Judäa im Jahre 6000 (2241 Christlicher Zeitrechnung), Dr. Foerster & Cie., Stuttgart, 1893

[64] Miriam Eliav-Feldon, ‘If You Will It, It Is No Fairy Tale: The First Jewish Utopias’, The Jewish Journal of Sociology, vol. XXV, no. 2, December 1983, pp. 85-103 – the quoted passage is from p. 89, and refers to p. 19 in the novel.

[65] Central Zionist Archives (CZA), H1\198, H1\198-2. This is in fact a draft of a letter, one that may never have been sent.

[66] See his ‘Prophesy and the Evangelization of the Jews’ in Charles L. Feinberg, ed., Focus on Prophecy, Fleming H. Revell, Chicago, 1964, p. 252.

[67] Cf. Moorhead, op. cit., p. 75, f. 34.

[68] I thank Shlomit Sattler, educational director at the Herzl Museum, for informing me that repeated searches over the years have failed to find any confirmation of anything from or by Blackstone ever having been on display – personal correspondence, 15 Dec., 2022.