Liam Hoare takes a look at how Israeli novelist David Grossman has responded to 7 October and the war that followed.

‘I will now say something controversial: since the Six Day War in 1967, we have not won a single war’, Amos Oz wrote in ‘Dreams Israel Should Let Go of Soon’, one of his final essays collected in Dear Zealots (2017). ‘The winner in war is the side that achieves its objectives, and the loser is the one who does not. We cannot win a war because we have no definitive national goals that can be achieved through military might’. Israel, Oz concluded, was trapped in a cycle of conflict management, ‘a recipe for one trouble after another, not to mention defeat after defeat’.

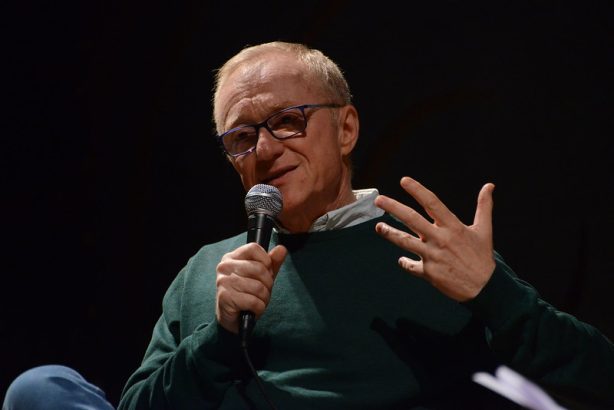

Israel is now six months into a cycle of conflict with Hamas than began with the pogroms of 7 October 2023. Five days after the massacres occurred, novelist and peace activist David Grossman published an op-ed in the Financial Times, now collected in his new pamphlet ‘Frieden ist die einzige Option’ (Peace is the Only Option, 2024), capturing the ‘feeling of fear seep[ing] in among those who are experiencing the terrifying prospect of defeat’. Months later, he wondered in the New York Times if the Israel would eventually be changed by the recognition that ‘this war cannot be won’.

7 October was, for Grossman as for Israel as a whole, a moment of earth-shattering trauma: ‘a nightmare. A nightmare beyond comparison. No words to describe it. No words to contain it’. Those Hamas operatives who infiltrated Israel by land, air, and sea, murdering over 1,000 people as they went, ‘lost their humanity’ on that day. Hamas’ victims, the murdered and the hostages, were ‘exposed to absolute, demonic evil.’ Somehow, even these words feel insufficient.

The slaughter constituted a shattering of illusions. ‘What do those who brandished the absurd notion of a “binational state” say now?’ Grossman asked. ‘Israel and Palestine, two nations distorted and corrupted by endless war, cannot even be cousins to each other—does anyone still believe they can be conjoined twins?’ As Oz wrote in his essay ‘Between Right and Right’, only once Israel and the Palestinians have conducted a ‘fair and just divorce’ can there be any reconciliation. ‘Rivers of coffee drunk together cannot extinguish the tragedy of two peoples claiming, the same small country as their one and only national homeland’.

7 October, then, went to something existential. ‘On that awful black Saturday’, Grossman describes, ‘it turned out that not only is Israel still far from being a home in the full sense of the word, it also does not even know how to be a true fortress’. He felt, in the days after the assault, a ‘deep sense of betrayal’ by the government of its citizens: ‘What we’ve seen is the utter abandonment of the state in favour of petty, greedy agendas and cynical, narrow-minded, delirious politics’.

‘I have talked with Jewish people living outside of Israel who have said that their physical—and spiritual—existence felt vulnerable during those hours’, Grossman observed, expanding his remit. ‘Some were even surprised by the magnitude to which they needed Israel to exist both as an idea and as a concrete fact’. Some, indeed, though it is perhaps more accurate to say that what 7 October has done is entrench people in their respective positions. Both Zionism and anti-Zionism have become, for its adherents, larger, more central, more urgent.

This goes not only for Diaspora Jews but all those engaged by this conflict, especially in protest movements in cities and on university campuses across Europe and the United States. The point that ‘Israel is the one country in the world whose elimination is most openly called for’ has been made often, but it is worth Grossman putting it so directly. ‘What [is it] about Israel that provokes this loathing[?]’, he asks. The answer may be something much darker.

Israel’s large-scale ground invasion of Gaza began on 27 October. Grossman seems to accept this response with a certain inevitability. Already on 12 October, Grossman was using language such as ‘after the war’, as if an Israeli military counter-operation was a foregone conclusion. While his writings incident neither a position for nor against the invasion, he is clear that the responsibility for this war lays with Hamas. ‘The occupation is a crime’, he wrote, ‘but to shoot hundreds of civilians—children and parents, elderly and sick in cold blood—that is a worse crime’.

Both in his op-eds and in ‘Peace is the Only Option’, Grossman is consumed by one question above all others: ‘Who will we be—Israelis and Palestinians—when this long, cruel war comes to an end?’ His mood is fatalistic, and his prognostications are shrouded with foreboding. ‘Israel after the war will be much more right-wing, militant, and racist’, he fears. ‘The war forced on it will have cemented the most extreme, hateful stereotypes and prejudices that frame Israeli identity’.

Another future may be possible. Polling indicates prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s popularity is in decline to former defence minister Benny Gantz’s benefit, though this may be a transitory phenomenon in the context of the Israel-Hamas war. Halted by 7 October, anti-government protests which began as a mobilisation against the government’s judicial reforms are underway again, this time questioning its handling of the Gaza counteroperation. Among the protestors are family members of hostages.

During the demonstration in Tel Aviv on 6 April, five protestors were injured in a car-ramming attack. Six months ago, Grossman asked: ‘Why is it that only threats and dangers make us cohesive and bring out the best in us, and also extricate us from our strange attraction to self-destruction—to destroying our own home?’ Temporarily stitched up by shock and a sense of patriotic duty, now the wound in Israeli society that Netanyahu’s government had poked and prodded is reopening and beginning to fester.

‘Who will we be when this war comes to an end?’ ‘The Palestinians will hold their own reckoning’, he writes, dodging that matter. As for Israelis, Grossman thinks the answer hinges on whether they can consider what he calls ‘our guilt for what we have inflicted upon innocent Palestinians’ during this counteroperation as well as the cost of living on a knife’s edge, ‘in constant watchfulness and suspicion, in perpetual fear’: ‘Who among us will decide that he does not want to—or cannot—live the life of an eternal soldier, a Spartan?’

Without a fundamental shift in the underlying conditions in the region, the future is predetermined. The cycle of conflict management Oz mentioned, one that has characterised the Israeli–Palestinian conflict for almost 20 years, will continue. Israelis and Palestinians remain ‘two tortured peoples’, Grossman rightly summarises: ‘The trauma of becoming refugees is fundamental and primal for both Israelis and Palestinians, and yet neither side is capable of viewing the other’s tragedy with a shred of understanding—not to mention compassion’.

His words recall another one of Oz’s pertinent observations from his essay ‘Between Right and Right’, collected in How to Cure a Fanatic (2012). The Israeli-Palestinian conflict ‘is essentially a conflict between two victims’ in which ‘each one of the parties looks at the other and sees in the other the image of their past oppressors’. Between the two parties runs a river of deep ignorance: ‘not political ignorance about the purposes and the goals, but about the backgrounds, about the deep traumas of the two victims’.

‘The coming months will determine the fate of two peoples’, Grossman concludes: whether Israelis and Palestinians will become more dug in or find a path towards a new reality. This is a war no side can win. ‘We will find out if the conflict that extends back more than a century is ripe for a reasonable, moral, human resolution’.