Sarah Tuttle-Singer is the author of Jerusalem, Drawn and Quartered: One Woman’s Year in the Heart of the Christian, Muslim, Armenian, and Jewish Quarters of Old Jerusalem and a writer for The Times of Israel. In this three-part series, Sarah soundtracks her Israeli experience. Through a series of songs, Sarah takes us on her journey from her first visit as a teenager from Los Angeles to the present day, as a mother of three Israeli children in the aftermath of 7 October. Part One can be read here.

MEIR BANAI – Sha’ar HaRachamim

The summer I was eighteen, I came back to Israel to volunteer on a Kibbutz. When the programme ended, I went to Jerusalem for a few days before my flight back to LA.

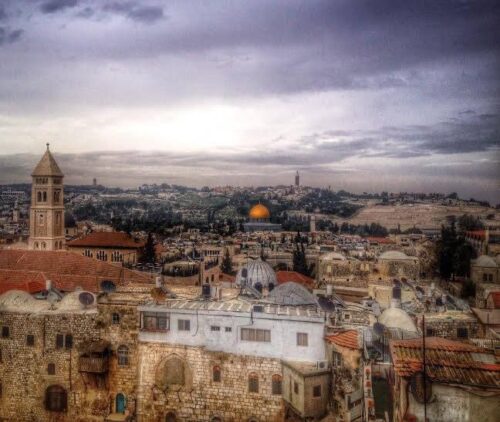

I had been to the Old City many times by then – but each time was curated and very specific… turn here, go there, eat felafel here, look at the amazing view there… this time, I was on my own.

I wasn’t expecting to walk up a narrow staircase and walk into another world, but I was exploring and I needed a place to stay.

The room was sky blue, and the entire eastern wall was a glass window overlooking the rooftops of the Old City.

The main room was strewn with Bedouin rugs, and there were hookah pipes, and a whole bunch of people just sitting there and smoking and talking, popping sunflower seeds, drinking coffee.

And there was music – Bob Dylan — ‘How Does it feel… to be on your own… with no direction home… .’

I could tell you how it feels because that’s how I felt. A few days before flying back to LA – dragging my feet along with my suitcase… but for that last Shabbat in Jerusalem, I could pretend I was free.

The guy behind the front desk was named Kobi — he had tattoos snaking up and down his arms, and there were track marks along the veins. He had a sunken face, except for his chin that jutted out and just dared you to punch it. I am sure no one ever did because he also had these eyes that were two hot coals, and there was no way to tell the difference between his pupil and his iris.

‘Let’s get a drink’ he said. And since you could drink legally at 18, I choked down Arak at a dusty little hotel bar just inside Jaffa Gate.

Kobi was divorced.

‘We used to live on a kibbutz,’ he said. ‘I moved here from Brooklyn, and met my wife, the fucking bitch. She ran off. She took the kids.’

‘Wow, that sucks,’ I said.

‘Yeah, if I ever see her again, I’ll kill that bitch myself.’

‘You don’t really mean that, do you?’ I said.

He laughed, and his eyes were dead.

(Now that I’m a mother all these many years later, I know he meant it.)

Kobi kept Shabbat, and as the sky began to turn a soft gold, he invited me to the Western Wall for candle lighting and prayers.

On the way there, he hummed a song.

‘That’s pretty,’ I said. ‘What’s it about?’

It’s called Shaar Harachamim. The Gate of Mercy, where some believe the Messiah will enter the holy city when he comes. The song is about wandering around the old city and feeling the power and hunger of this place in your soul – and understanding that it’s part of you, too.’

‘Wow,’ I said.

Kobi stopped by one of the stores in the shuk. The whole world was hazy and gold and smelled like rose petals and the bottom of a river.

‘Hey brother,’ he said to one of the shopkeepers, ‘can I get a pen?’

‘If you pay for it,’ the shopkeeper said.

‘Nu…’

‘Business is business and I have a family to feed.’

‘Fine,’ Kobi handed the shopkeeper a few coins. The shopkeeper gave him a red pen with “Jerusalem” on it beside a heart and a jaunty camel.

‘You got paper?’

‘I’ll give you a piece of paper for free if you say a bracha for me at the Wall.’

‘But you’re not Jewish!’

‘So what?’

‘Deal.’

They shook hands.

Kobi quickly wrote in English:

Walking around the old city

And noise comes from every corner

I already know, I already know my way

The road to the gate of mercy

Not looking around, not listening

I am a dreamer, and have always been

But I already know, I already know my way

The road to the gate of mercy

You live once, only once

There is a point, there is no point

With power, without power

Gate of Mercy

Come with me

Come out of fear

Because you too, you are part

Of the Gate of Mercy

The signs above the shops

Overlooking the streets

There is a cry inside my heart, and it is loud and mighty

I was shown the gate of mercy

‘See?’ He said. ‘This song is about all of this…’ he waves his arms in every direction. ‘This,.. this feeling, this light, this desire, this continuity… all of this… being part of living history, of God, inside the arms of this beautiful city who will always love us… as we search for redemption, feeling all the feelings inside us… passion, grief… yearning for that higher place… being loved despite all my mistakes and the things I’ve done wrong… this feeling is what keeps me here, keeps me hoping that one day I’ll see my children again…’

I felt my eyes grow hot with tears.

‘Nu,’ Kobi said ‘it’s not all bad. I get to be HERE. And I’m with HER the whole time.’

‘Her?’

‘Jerusalem. The love of my life.’

‘I understand,’ I said.

But I’m not sure I really did then — at least not on the same cellular level that Kobi shared with me that late Friday afternoon. But I never forgot what he said or how I felt hearing it, or how the air in the Old City shimmered in the setting sun and the rough stones turned to the softest satin in the fading light.

And years later, when I had moved here as I swore that I would one day, after a lot of living, loss and love, I understood what he meant. I’d walk the streets of the Old City, past the signs above the shops, hearing the noise from every corner, the cry in my heart loud and mighty as I feel the embrace of Jerusalem around me like my mother’s arms, home.

OFRA HAZA – Im Nin’Alu and Frecha

I had just moved to Israel, and this was the second night of my first Hanukkah where I could say ‘a great miracle happened HERE.’

The whole world smelled like latkes. But I wasn’t in the holiday spirit, because – O irony of ironies! – I was homesick for Los Angeles. Specifically, for my mother’s kitchen, and the latkes she’d make every year for Hanukkah.

I think the homesickness that day was bigger and deeper than I wanted to admit. After all, I had what I wanted: I was finally living in Israel… but the fact is, it’s one thing to go on a trip to Israel for a summer when you’re a teenager and frolicking around with hot Israeli soldiers and eating free felafel, and quite another when you’re a mother of two, and trying to get your footing in a completely new world.

The kids had been sick off and on since we landed, I was exhausted, and I was lost. Metaphorically, totally. And also physically. Literally. I didn’t know that part of Jerusalem AT. ALL. Back then.

But I DID manage to find Shuk Mahane Yehuda because I followed a familiar voice. The voice of an angel.

Ofra Haza — AKA ‘The Madonna of the Middle East’ was on full blast. Ethereal, haunting… I knew her from since forever it seemed.

Im Nin’alu.

I felt the whole song fill me, along with the memories of discovering this song when I was a teenager and back in LA and stalking every felafel joint in the San Fernando valley where the Israelis hung out. This song was part of that time when I yearned for Israel – and I had forgotten that feeling, but there it was again, filling me with light from my toes to eyelashes.

I brushed the tears away.

The melody is an exquisite blend of East meets West.

The sound itself is modern, but with an ancient twist; and the words Ofra Haza sang so powerfully come from the Hebrew poem by 17th–century Rabbi Shalom Shabazi.

Even if the gates of the rich are closed, the gates of heaven will never be closed.

The song ended, and another one came on:

Frecha.

Not gonna lie: that song was MY JAM back in the day when I was reeling in the cosmos of being head over heels in love with Israel. The song is fun, it’s playful. It’s an audacious, hot pink song:

Because I want to dance, I want to do crazy stuff.

I want to laugh – but I don’t want you!

…

I want to shout, I’m a FRECHA!

There was a man with white hair selling clementines and pink grapefruit piled high beside him.

‘Ofra Haza,’ he said, waving his hands around with the music. ‘The beautiful Ofra Haza!’

I smiled.

He told me he had a bum knee, a sore wrist, and three grandchildren.

He also told me he hoped he’d get to see them over Hanukkah. ‘If they aren’t too busy. May Gd protect them.’)

‘I love this song,’ I told him. ‘It’s one of my favourites!’

‘Of course you do!’ he answered. Ofra is from our generation!’(I decided not to ask exactly what generation this grandfather of three thought I was in.)

‘But how do you know her?’ He asked. ‘You’re American! Was she famous there?’

I wiped my eyes.

‘I used to listen to her music in LA,’ I answered, and I told him about the place where I would go, the little pocket of Bat Yam on Ventura Boulevard where Pini Cohen would sing all the best songs and all these gorgeous, juicy women in their forties and fifties — self proclaimed ‘frechot’ like Ofra Haza – would climb on the tables and shake and shimmy their shoulders and their breasts and wave their arms in the air while their golden bracelets jangled and the ice cubes in their pretty drinks clinked.

The men all wore black shirts and black pants, sometimes tight jeans, hair gelled – (if they had any hair,) Aqua Di Gio splashed across their faces and chests.

Those who weren’t dancing were making business deals – ‘imports exports’ b’tachat sheli – or arguing about politics — or desperately trying to convince their dates to kiss them, go home with them, or marry them… forever! Or for a green card.

Some things never change. Bibi was prime minister even then.

If you were to squint your eyes, you’d be on the other side of the world, in another world completely, where Ricky Ricardo’s Tropicana meets the Casbah meets the Shabbos dinner table.

I loved it.

It was my portal back to Israel.

(And hearing Ofra Haza again in the shuk that day was my portal back to LA.)

I remembered how I loved the sound of it all those years before – Zohar Argov and Ishai Levi and Sarit Hadad and Haim Moshe and ALWAYS Ofra Haza. The passion in their singing, the joy, the longing.

‘This is such a great song,’ I said. ‘But I haven’t heard it since I was a teenager.’

‘But you’re STILL a teenager!’ the shopkeeper answered. ‘You’re just a kid!’

I laughed. I was neck deep in my thirties at that point. And also from ‘his generation,’ as he had said earlier .

And listening to Ofra Haza in the shuk, my heart expanded to fill the space between my past – dancing on tables and yearning for Israel – and my possible future – where one day I’ll have white hair and a bum knee and a sore wrist and God willing, grandchildren who may or may not have time to see me – and I felt my heart firmly rooted in the present moment, building a life here in the place I chose all those years ago – literally home here and buying my groceries in the market stalls of Jerusalem just as I had dreamed of doing when I was a teenager — my heart, a bridge between these different places and different times, and I am STILL to this day all of these things at once.

And the shopkeeper — a grandfather of three — with his white hair and bum knee and sore wrist, winked at me as though he knew what I was thinking. And he’s just a teenager, too.

TAMER NAFAR – Ya Reit

The taxi driver was listening to a bop.

I love it.

‘That’s Tamer Nafar, sah – right?’ I asked.

‘Sah, right. You speak Arabic?’

‘A little,’ I answer in Arabic.

‘But you’re a Jew?’

‘Yes.’

‘That’s cool you speak Arabic. But Jews here only know how to say ‘open the door,’ or ‘freeze or I’ll shoot!’

‘Hey, that’s not fair! We also know ‘kus emek’ and ‘sharmuta’’

He laughed.

But it was a dry and tired laugh.

I’ve been in Israel long enough now that not everyone has sanguine feelings about this place — and for many Palestinian Jerusalemites and/or citizens of Israel, there is an often constant struggle blending Palestinian heritage and identity with Israeli citizenship.

It’s even more fraught than that:Despite being an integral part of Israeli society, Palestinian citizens of Israel often face systemic discrimination and prejudice, manifesting in unequal access to resources, employment opportunities, and political representation. This prejudice stems from historical tensions and ongoing conflicts — plenty of anger, even more fear — perpetuating social and economic disparities within the community.

As a teenager, it was easy for me to dismiss the very real pain in the community, but after living here and talking to all sorts of people, I know it’s possible (though certainly not easy) to hold multiple truths at the same time, and I’m working on it.

One of the artists that I looked to for help FEELING these complexities – even as an outsider – is Tamer Nafar, a prominent Palestinian–Israeli rapper.

I guess he might not love the idea of being on a list of Israeli artists who shaped my identity.

I get that.

But, technically, he IS an Israeli citizen, and he continues to shape my identity when it comes not only to the music I love but also to the work I try to do strengthening shared society here in this little piece of fraught and holy real estate.

And I love the music itself: he typically incorporates a mix of contemporary hip–hop and rap styles with elements of traditional Arabic melodies. And the words are even more powerful — pure poetry meets a punch to the gut, as he sheds light on the prejudices, the discrimination, and the societal inequality he and members of his community face Every. Single. Day.

‘I really like him,’ I told the driver. ‘Especially the song Ya Reit from his movie Junction 48. Haunting, strong — and I love that he threaded in the poet Mahmoud Darwish.’

‘He’s talented,’ the driver said. ‘I like him – but he’s always so negative all the time. Yeah ok, he isn’t wrong – there’s corruption, the police are terrible and don’t protect Arabs from violence and crime, there’s racism and there’s always the Occupation, but he isn’t offering real solutions to these problems or even any hope for a better future.’

‘He’s angry, I guess,’ I said.

‘Yes, ok and sometimes I’m angry too,’ the driver said. ‘But –‘maybe I’m just older and I’ve seen a lot — but I know this: we need each other. Jews and Arabs. This place belongs to both of us and neither one will succeed without the other. And we need hope in order to make peace between us. Just a little hope.’

I think about what he said often – especially now in the middle of this terrible war.

And I try always to remember: This isn’t a war between Israelis and Palestinians. This is a war between the forces of darkness and the forces of light that exist in both our societies. The forces of death and destruction and war and the forces of life and creation and peace.