‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past.’ – William Faulkner

In the early hours of 14 June 2017, London’s residential high-rise Grenfell Tower caught fire. Seventy-two people lost their lives in the subsequent inferno and many more were made homeless. It was Britain’s most deadly peacetime tragedy for over a century. As the charred building smoldered, Londoners went into action, donating food and clothing and volunteering at emergency shelters. One of these volunteers was a woman named Tahra Ahmed. She had asked herself the question demanded by countless other furious Britons – How could this outrage happen? – and she was convinced she knew the answer. She shared it with Facebook:

Watch the live footage of people trapped in the inferno with the flames behind them. They were burnt alive in a Jewish sacrifice. Grenfell is owned by a private Jewish property developer just like the twin towers was owned by Jew Silverstein who collected trillions in insurance claims. … LONDON TOWER BLOCK FIRE: SINISTER CONNECTIONS WITH JEWISH RITUAL SACRIFICE EXPLORED.

Ahmed was prosecuted for stirring up racial hatred and used her day in court to defend her beliefs. She claimed that Jewish religious texts including the Talmud permit ‘sacrificing children’ and that medieval myths that the Jews would kidnap and kill Christian children in a religious ritual might be true. She denied that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust; said 9/11 was probably carried out by the Mossad; and claimed there is a ‘Talmudic’ ‘Zionist’ powerful ‘cabal’ of Jewish bankers and other powerful Jews responsible for much of the world’s evil.

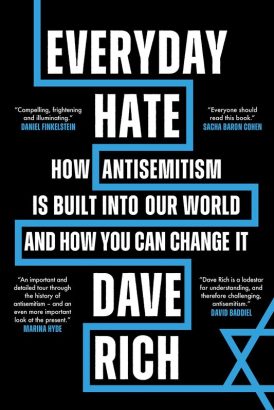

As Dave Rich patiently explains in Everyday Hate and Fathom readers will know, none of Ahmed’s claims were true. The question Rich explores is: where do these bizarre ideas come from? When Kanye West called for ‘death con 3’, why was it on ‘JEWISH PEOPLE’ of all things, and why did this threat get 30,000 ‘likes’ on Twitter before being deleted? Why do so many people hold ‘the Jews’ responsible for Covid? Where did the satirical show South Park get the idea to write an episode featuring a non-Jewish character demanding a Jewish one hand over the ‘Jew gold’ he knows the Jew keeps in a bag around his neck (which the Jew hands over, after slyly trying to pass off his fake one)? Why is the idea of ‘Jew gold’ even a thing? And why does the word ‘Jew’ in both sentences preceding this one sound offensive somehow, even though it’s just the noun for a Jewish person?

Rich answers these questions and more brilliantly, in a fascinating, disturbing, beautifully written work that teases out the connections between present-day antisemitism and its historic roots. It’s a palimpsest, in which the past is seen as continually rising to the surface in determining the shape of contemporary tropes and beliefs about Jews. Like ‘hikers following a trail across unfamiliar terrain’, he writes in an elegant metaphor, those who subscribe to these beliefs ‘are walking a path trodden into our world by millions of people before them in times long forgotten’.

He provides a synthetic overview of this history, focusing on England. The country which has been a relative haven for Jews for many years is also the country that invented the blood libel: the myth that Jews, collectively guilty as Christ-killers, thirst for Christian blood and ritually murder its children. The world’s first blood libel occurred in England in 1144, when the Jews of Norwich were accused of not only murdering a twelve-year-old named William, but of reenacting, at Easter, the crucifixion of Jesus on the boy. This lethal lie (and antagonism against Jews as ostensible usurers) was repeated in village after village, resulting in communal violence against Jews. ‘In time’, Rich writes, ‘a profound way of interpreting the world emerged in which Jews and Judaism were positioned as conceptually opposed to everything that is good, wholesome, and humane. If you are asking where antisemitism comes from, why the Jews, and how it all began – this is as good a place as any to look for an answer.’

This wave of anti-Jewish violence ended with the expulsion of the Jews in 1290 – the first country in the world to do so. The near-total lack of Jews in England didn’t stop Chaucer in the 14th century from penning a poem in The Canterbury Tales about Jews who are ‘hateful to Christ’, ending the tale by hanging them as child-killers. (As Rich mildly observes, it’s striking how little the antisemitism of this classic work is acknowledged: there’s ‘no 21st-century trigger warning’ here.) Nor did the dearth of Jews stop England’s justly celebrated playwright William Shakespeare from giving the world one of its most enduring villains in Shylock, the venal Jew who thirsts for his ‘pound of flesh’.

Looking back on the early pattern of English persecution of the Jews – from defamation, mob violence and legal oppression to elimination – Rich observes that it loosely resembles the incremental steps taken by the Nazis over a much shorter period hundreds of years later. It isn’t that one inspired the other, he emphasises, ‘but the imprint of medieval antisemitism is detectable centuries later, like a fossilised footprint in the rock in which water pools the same way every time it rains. This history matters.’

This is the past that isn’t past when people – whether on the political right or left, religious or secular – single out Jews as ‘the example of how not to be: the opposite of what is considered good, moral and just’. As Rich puts it:

Jews have long been Europe’s traditional ‘Other’, but this doesn’t only mean they have been an unwanted minority: it incorporates a more profound imagining of Jews as a representation of the evils that need to be purged to make the world pure. This is why it is so striking that Israel, the most visible global expression of Jewish life today, is held up as the archetype of a human rights transgressor in a world in which human rights are the highest measure of moral good.

Antisemitism does more than provide a scapegoat. Uniquely among forms of racism, it provides adherents a seemingly all-encompassing explanation for why evil exists. From the time of the first blood libel, Jews have been cast as not only an enemy, but an ordinately powerful, sinister, scheming one. (As Theodor Adorno put it in a nutshell, ‘Anti-Semitism is the rumour about the Jews.’) Covid has inspired a spike in conspiracy theories that blame the pandemic on Jews. Those who spread this lie unwittingly invoke the 14th century, when Jews in continental Europe were blamed for spreading the plague by poisoning wells.

The lodestar of present-day conspiracy theories, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, ‘built a bridge into modernity’ for Europe’s traditional anti-Jewish mythology. The idea that all Europe’s problems were caused by Jews just seemed to make sense on a visceral level. The Protocols were tremendously popular in Britain, with respectable newspapers enthusiastically asking if it was genuine. The fact that it was soon proved a Russian fake did little to stem its appeal; it remains all too alive today. Conspiracist theories around Brexit, with George Soros deployed as a demonic figure seeking to undermine democracy, invoke the same tropes. At the same time, conspiracy theories about Israel gain traction in the popular imagination because Israel is Jewish: ‘They latch onto pre-existing beliefs about how Jews behave, like a climber using footholds cut into the rock by those who have scaled the same mountain centuries before.’

Rich illustrates this last point with an episode from the Second Intifada in 2002. There, Palestinian fighters, some from a group called the Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade, took refuge in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, which was surrounded by Israeli forces, resulting in a five-week siege.

‘Imagine this,’ Rich prompts:

one of Christianity’s most sacred sites, the birthplace of Jesus himself, at the centre of a standoff between fighters named after one of Islam’s holiest mosques and soldiers from the first Jewish sovereign military force since Jesus walked on that same land. There is nowhere else on earth that anything remotely as culturally, religiously or politically resonant could happen.

It is simply improbable that Israel’s fiercest critics are able to detach themselves entirely from their own cultural moorings when deciding who to boycott, which march to go on or where to lodge their moral protests.

Rich calls himself an optimist, but as he writes in his final chapter ‘Things Can’t Only Get Better,’ there’s plenty to worry about. It isn’t ‘only’ that polls and tallies of hate crimes consistently show antisemitism to be rising, but there’s a troubling generational shift: today’s teenagers, millennials and young adults are much more likely than their parents to subscribe to antisemitic conspiracy theories. One of many opinion polls, for instance, found that British adults under the age of 34 were up to five times more likely than those over 55 to agree that ‘Jews have disproportionate control of powerful institutions, and use that power for their own benefit and against the good of the general population.’ The concern isn’t so much the overall numbers, which are currently small, so much as ‘the direction of travel’.

This seems like a paradox, because British adults under the age of 34 are also the least likely age group to describe themselves as racially prejudiced and were most likely to support the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. This points to a huge shift in the popular understanding about what racism is, and it’s a shift that leaves the door wide open to antisemitism. According to the thinking which has taken hold over the past couple decades, racism is a system perpetrated by privileged white people against dark-skinned ones. According to this framework Jews, whatever their skin colour, are cast as privileged and white, rendering them eminently hate-worthy. The Israel-Palestine conflict is also claimed to be a manifestation of Western colonialism, so Israel and its Jewish supporters are condemned for ‘racism’, the ultimate sin.

This helps explain young people who simultaneously declare themselves anti-racist and hold antisemitic beliefs that would have appalled people fifty years ago. As Rich writes: ‘At its core, the difference between racism and antisemitism is the difference between a prejudice and a conspiracy theory; and while prejudice is out of fashion for today’s youth, conspiracy theories are all the rage.’

Rich doesn’t claim any of this is readily fixable given the intractability of antisemitism, but notes that it’s nevertheless the Jewish tradition not to give up on trying to improve the world. He provides several discrete goals to work toward, beginning with ensuring that the understanding of racism includes antisemitism. Consistently include Jews in ethnicity-based monitoring of exclusion and disadvantage, he continues, and measure specifically antisemitic tropes and conspiracy theories. Stop leaving it to Jews to teach about the history of antisemitism, since it’s not the story of what Jews did; make it part of national museums and education. Debunk conspiracy theories before people encounter them – a method known as ‘prebunking’ that seems to really work. Hold social media companies accountable for aiding the spread of conspiracy theories. Beyond trying to limit the spread of negative ideas about Jews, Jews should try to encourage the spread of positive ones; it’s truly beneficial when Jewish and non-Jewish children and adults have structured contact. Some of the challenges Rich suggests are more difficult than others, but taking on any or all will play a role in fighting this ancient hatred.

Dave Rich has written a wonderful book. For those who want a comprehensive account of where antisemitism comes from and how to fight it, it’s essential; for those who haven’t given it thought, it’s even more so.

You say that “it’s truly beneficial when Jewish and non-Jewish children and adults have structured contact.”

Social psychologists and particularly the late Gordon Allport have well and truly debunked this so-called contact hypothesis. It doesn’t work because Jews who mix with and are liked by non-Jews are deemed to be exceptions to the rule. “You’re OK”, they say; “it’s all the others who are …..” (fill in the blanks).