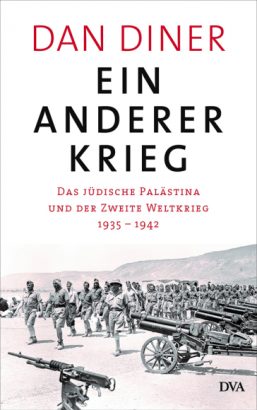

Derek Penslar reviews Dan Diner’s, Ein anderer Krieg: Das jüdische Palästina und der Zweite Weltkrieg – 1935 – 1942 (A Different War: Jewish Palestine and the Second World War) (Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 2021). Penslar is the William Lee Frost Professor of Jewish History at Harvard University. His book Zionism: An Emotional State will be published next year by Rutgers University Press.

In 1939 the Zionist movement faced a terrible dilemma. In May of that year, the British government issued a White Paper that abrogated the Balfour Declaration. Instead of promoting the development of a Jewish national home, the British now intended to throttle Jewish immigration to Palestine and for it to become a unitary state with an Arab majority. Less than four months later, Germany invaded Poland and Britain declared war on Germany. Caught between the hammer and the anvil, David Ben-Gurion, Chair of the Jewish Agency Executive and the leader of Palestine’s Jewish community, proclaimed that ‘we shall fight [alongside of Britain in] this war as if there was no White Paper and we shall fight the White Paper as if there was no war.’

Dan Diner’s wide-ranging and brilliantly conceived book tells the story of both wars, and in so doing he demonstrates how in both cases the Zionists and Palestine as such were minor players in the most catastrophic conflict in world history. Diner decenters Eurocentric perceptions of the war, presenting it from a global geo-political perspective. Palestine lay at the confluence of the war’s European, North African, and Middle Eastern theaters, but for the British and Germans alike it was a way station to India. Seen from Africa and the Middle East, the war began with Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, and its worst days were over by November 1942, when the German advance was stopped at El Alamein, only a hundred kilometers from Alexandria. Hence the chronology in the book’s subtitle, although Diner’s discussion of the war’s other theaters, and on Jewish responses to the Holocaust, goes up to 1945.

The Middle East theater consisted of multiple, interlocking, and constantly moving parts. Iraq was a haven for Arab nationalists, including exiles from the failed 1936-1939 Palestinian Arab rebellion such as the Mufti of Jerusalem, Mohammed Amin al-Husseini, and the rival military commanders Abdel al-Qadr Husseini and Fawzi Qawukji. Hostile to Britain for its ongoing influence over Iraq, in April 1941 the Iraqi politician Rashid Ali al-Gaylani led a coup that had military support from Nazi Germany and was hailed by the Soviet Union, which at that time was allied with Germany, as a triumphant blow against anti-imperialist capitalism. British forces suppressed the coup within a few weeks, and in June Germany invaded the Soviet Union, leading the British and Soviets to become allies and jointly occupy Iran in August and September. (Diner notes ironically that Soviet soldiers went from marching side-by-side with Nazis in Brest-Litovsk to marching side-by-side with the British in Tehran.) The new alliance brought into Soviet hands millions of tons of Allied weapons and goods shipped via the Persian Gulf, Iran, and Soviet Azerbaijan. Without that assistance, it is doubtful if the Soviets could have withstood the Nazi onslaught during the winter of 1942.

The Allies’ expulsion of Vichy forces from Lebanon and Syria in the spring of 1941 did not scuttle German plans to break through to India via a pincer movement from North Africa and the Middle East, on the one hand, and the Caucasus, on the other. In order to protect India, Britain was willing to give up Palestine and Egypt and hunker down in Iraq. This position could not, however, defend India from a Japanese assault through Burma. Indian support for the war effort was, therefore, essential, but in the spring of 1942 the Indian National Congress demanded the withdrawal of all foreign troops and immediate independence for India. (At this point Gandhi rejected any British compromises regarding ongoing colonial rule to be ‘a post-dated check drawn on a failing bank.’). The anti-British and pro-Japanese Indian National Army, led by Subhash Chandra Bose, siphoned off young men who might otherwise die for Britain. Desperate to maintain the loyalty of Muslim men, who were the largest component in the British Indian Army, the British were in no mood to do anything that might seem to favour Zionism.

This is where Jews enter Diner’s book – not as central actors so much as peripheral characters, victims outside of Palestine and helpless bystanders within it. In Iraq, the consequences of Rashid Ali al-Gaylani’s putsch for the country’s Jews were dire. Yunis al-Sabawi, who had translated Hitler’s Mein Kampf into Arabic, became a minister in Rashid Ali’s regime. Among the Iraqi public, rumors swirled that Jews were providing signals for British bombers. (Similar accusations that Jews transmitted information to the enemy via secret telegraphs, even though all wires had been cut, had been a staple on the Eastern Front in World War I.) At the beginning of June, at least 150 Jews died as the result of rioting in Baghdad (the Farhud).

Italian, German, and Vichy French bombers pummeled Haifa and Tel Aviv in 1940 and 1941. In July of 1942, as Rommel’s forces closed in on Alexandria, Zionist leaders debated if they should make a heroic last stand, fighting to the end, or form an underground partisan force that would form a chronic irritant to the Nazi invaders. Proposals to hole up in the Carmel mountains were drawn up but never fleshed out. Reflecting the spirit of the time, the Labor Zionist poet Natan Alterman wrote in his masterpiece The Joy of the Poor, ‘I see you armed, I see you desperate, my brazen remnant/I saw you and understood how thin is the line/ between the verge of catastrophe and the eve of jubilation.’

After the German defeat in November, the nightmare passed, and the blackouts in Palestine’s cities were eventually lifted, but the dilemma remained – how best to pursue the fight against both Hitler and the White Paper?

One answer for the former was to join the British forces, which Palestine’s Jews did in considerably higher proportions than Palestine’s Arabs. But Zionists of all types – ranging from firebrand Revisionists to mainstream leaders like Ben-Gurion and Chaim Weizmann, and even Zionism’s gadfly on the Left, Hannah Arendt – wanted something more: a Jewish army with its own flag and insignias, akin to the Polish, Lithuanian, and Czech armies in exile. Champions of the armies in exile claimed that participation in battle as a national unit would lead to collective liberation and restoration after the war.

From Britain’s perspective, however, with Hindu nationalism opposing Zionism out of anti-colonial principle, and South Asian Muslims proclaiming solidarity with their brethren in Palestine, it would have been no less foolhardy for Britain to pursue a pro-Zionist policy during the war than in 1939, when the White Paper was issued. Doing so could have had a negative effect on relations with not only India but also Egypt (whose relations with Britain at the time were also strained) and neutral Turkey. The Polish forces in exile commanded by Władysław Anders did not threaten the stability of the British empire. The same cannot be said for a Jewish army. When in the fall of 1944, Britain finally agreed to the creation of a distinct Jewish brigade, 5000 strong, it was commanded by Gentile as well as Jewish officers and deployed away from Palestine – primarily in Italy.

The Zionist struggle against Britain was of far greater significance in Jewish history than the Zionists’ role in the fight against Hitler. The Extraordinary Zionist Conference held at New York City’s Biltmore hotel in May 1942 directed its attention not to the war but to, as Diner cleverly puts it, ‘the war after war.’ The conference marked the first time that the Zionist Organization called for a Jewish state. (The Basel Program of the First Zionist Congress of 1897 had called for a ‘publicly-recognised, legally assured homeland in Palestine,’ a deliberately ambiguous term crafted by Theodor Herzl himself.) The Biltmore Program used the term ‘commonwealth’ rather than ‘state,’ but the intent was clear. Moreover, this state was, according to the Biltmore Program, to be established in the entirety of cis-Jordanian Palestine. Aside from its political and territorial maximalism, the conference was revolutionary in other respects, marking the decline of the moderate Chaim Weizmann and the rise of the more militant Ben-Gurion in international Zionist diplomacy, the Zionists’ turn from the United Kingdom to the United States as the movement’s primary protector, and the growing influence of American Zionism in the face of the destruction of European Jewry.

At the time of the conference, the full extent of the Holocaust’s destruction was not yet known. The most painful chapter in Diner’s book is his account of the skepticism and even hostility with which some leaders of Palestine’s Jewish community greeted eyewitnesses to the genocide taking place in Europe. Their insensitivity is shameful, and today we may cringe at debates among Zionist leaders whether to spend money on rescue attempts in Europe or the afforestation of Palestine’s barren mountains . There was, however, little that Palestine’s miniscule Jewish community, numbering 600,000 in all and four thousand kilometers from Auschwitz, could have done to save Europe’s Jews from annihilation. To the extent that wartime Zionism did engage in rescue activity, e.g., the transport of Jewish refugees across the Mediterranean, any such work was made possible because of the Allied militaries’ elimination of the German threat from North Africa and the expulsion of Vichy forces from the Levant.

Here we come back to Diner’s main argument. Allied military power saved the Jews of Palestine in 1942. It did not intend to help them but rather to secure Palestine, or, more accurately, British imperial interests in the Middle East and, ultimately, India. Moreover, Palestine was a sidenote to the Middle Eastern and North African theaters. It was a meeting point between the war’s major theaters but not a focal point. Diner asks why this moment of peripherality, on the one hand, and total dependence, helplessness, and panic, on the other, has been expunged from post-war Jewish collective memory. We see the answer in the final chapters of Diner’s absorbing narrative. Despite the realities of Zionist dependence on Great Power protection from its origins to the present day, the state of Israel cultivates a myth of independence, a myth that dates back to the concept of self-emancipation pioneered by early Zionist thinkers such as Lev Pinsker and Theodor Herzl. And, like most myths, this one has a nugget of truth: although the United Nations and dozens of individual states provided diplomatic legitimisation for the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine, Israel’s establishment in 1948 was enabled by a war that mobilised the newborn country and killed thousands of its youth.

Alongside of dependence come contingency and uncertainty. As Diner notes in his Conclusion, Jewish survivors of the Holocaust were not welcome in postwar Europe’s now ethnically homogeneous states. Millions of ethnic Germans had been expelled from eastern Europe, Ukrainians had been driven out of Poland, and so on. Stalin was all too happy to see Jewish refugees funneled away from the Soviet Union, despite its claim to national heterogeneity, and shunted to Palestine, where they could discomfit the British and perhaps form an anti-western, socialist vanguard. European Jews who survived the war knew that the newly born state of Israel may not be any safer than where they were at present, but after everything they had been through, they wanted to live with other Jews.

As a producer and receiver of masses of refugees – Palestinians on the one hand and Jews on the other – Israel was part of the postwar global political order. What Arie Dubnov calls Israel’s war of partition in 1948 paralleled the catastrophic partition of the Indian subcontinent in the previous year. The particular aspects of Israel’s creation – linked with the destruction of European Jewish civilization and the dispossession of the Palestinian people – do not lessen Zionism’s embeddedness in the geopolitics of the wartime and postwar environments.