Yael Halevi-Wise marks the passing of her friend, the Israeli novelist, short story writer and playwright, A.B.Yehoshua. Author of The Retrospective Imagination of A.B.Yehoshua (Penn State UP 2020) she hails his pathbreaking literary and political output, always ‘tethered to his lifelong preoccupation with a reconfiguration of modern Jewish identity in Israel’

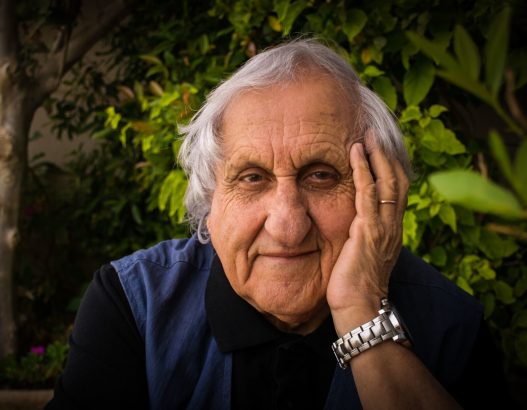

Two photographs of A. B. Yehoshua hang on the walls of my study, actually three if one looks more closely. The first is a clipping from a newspaper – wide eyed college students surrounding the elderly author, amazed that such a well-known man had taken the time to speak to them warmly and personally during a mere class trip to Israel; they are even more amazed that he yelled at them to start taking their Jewish identity more seriously. In another image, my favourite, Boolie’s fists are up in the air; he’s at home talking animatedly with an invisible interlocutor. Behind his shoulder we can discern a framed snapshot of Boolie as a relaxed family man. He is crouched on the ground with one of his granddaughters and they are playfully staring deep into each other’s eyes.

Obituaries in Israel and everywhere have been announcing that this major 20th century Jewish author has passed away; but can such a figure ever pass away? I feel today that the French cultural theorist Roland Barthes did not see far enough when he declared ‘the author’ dead. True enough, even in the prime of his life Yehoshua tended to be opaque when he threw dust in our eyes by offering specific interpretations of his fictional worlds. When approached with direct questions about his literary intentions, he rarely answered in a useful manner, either.

For instance, I couldn’t figure out why in Mr. Mani, Yehoshua’s chef d’ouvre, a baby born to Zionist pioneers in 19th century Jerusalem never gets to breathe the breath of life, while a baby born to an Arab couple that same evening in Dr. Moshe Mani’s inclusive clinic, thrives despite contracting jaundice. Why did you kill the Jewish baby, I asked Boolie, and on Yom Kippur of all days? Twenty five years had passed already since he had composed that scene; and by now, the author too was puzzled. Really, why, he asked me back. That day I learnt that one can be in the enviable position of posing any question one wants to a beloved author, but the author might not have a good answer. Either he forgot his intention or the question appears to him trivial: ‘why do you keep harping on this detail!’ He preferred to talk about ideas of more recent vintage.

His literary and political output, however, was tethered in one way or another to his lifelong preoccupation with reconfiguring or updating Jewish identity in light of the recent return to national sovereignty. He was full of sound and fury for the sake of examining this process of modern national repair from a moral and practical point of view. Seeking a state of ‘normalcy’ – a psycho-political condition that he called normaliut and viewed slightly differently from the standard Zionist vision – was according to him, ‘nothing but a rich and creative pluralism in which one is as sovereign as possible over one’s deeds, and where the options on the horizon are vast.’1 Many aspects of the relationships between his characters model how this type of cultural environment can be worked out – or missed – across generations and national borders, between Jews and others. No Israeli corner was too parochial for him and no global location too exotic to send his troubled characters there to meet and interact with members of other tribes, other religions, ethnicities or national groups from which they learn about themselves. Staged as highly strung conversations, these meetings enable his characters – and by extension us, his readers – to examine each other’s supposed identities, which are inevitably rooted in murky expectations and long held myths that must be taken seriously, nonetheless, if they are ever to be rehabilitated.

Stylistically, he packaged these ideas into a literary multilayeredness that allowed him to project religious dilemmas and key historical references upon a microcosm of Israeli life. At first glance, Yehoshua’s microcosm of Israeli life may strike us as absurd and often humorous – a family man pursues his wife’s lover to push him back into the wife’s bedroom; an expatriate Israeli musician returns temporarily home and finds herself employed as an ‘extra’ in the film industry; an elderly engineer with encroaching dementia forgets his name while designing a tunnel meant to hide a fugitive ensconced on a Nabatean hill in the Negev – but behind this surreal combination of details, appears a sober examination of Israeli life resonant with political history and traditional cultural symbolism.

More extensively than Agnon or any other Jewish writer, Yehoshua’s multilayeredness takes the form of dialogues between members of different cultural groups. These conversations staged in Israel and abroad open up bridges of communication between Jews, Muslims and Christians, Sephardim and Ashkenazim, the elderly and youth, religious and secular people, men and women, straight and gay. Yehoshua never loses track of the geopolitical implications and historical contexts that permeate these cultural meetings. Because, for him, the present is an historicised juncture that entails crucial new choices with new responsibilities and far reaching consequences.

I believe along with Israeli literary scholar Dan Miron that A. B. Yehoshua’s creative work will be recognised as the most important literary achievement in modern Hebrew since Agnon. Yehoshua was the trailblazer who signalled to Amos Oz, Amalia Kahana-Carmon, Haim Beer and others that to matter locally and internationally, their generation of writers and intellectuals should adopt Agnon’s and Mendele’s haskalaic method of turning delectable descriptions of the ‘here and now’ into a vital reassessment of Jewish identity and traditional lore.

Barthes may have been right regarding our ultimate lack of access to an author’s ideological intentions. Yet past and future communications inevitably merge when we continue to sift through a shelf full of novels, short stories, essays – as well as many interviews and recordings of public talks – to carry on the conversation into which Yehoshua hooked us through his absurd plots and cagy allusions. Admittedly, I long to hear him call me habibti again in the intonation of my Jerusalemite Sephardic grandmother. It is indeed too painful to process the notion of not being able to dial him up to discuss his latest manuscript draft, to argue about his most recent annoying recommendation for the stability of Israel’s identity in our postmodern world, and to tell him that the newspapers are claiming he passed away.

I prefer to imagine this author as not dead: he invited us to maintain a vital conversation about Jewish identity, about our need for national renewal, friendship and family life. It’s up to us to keep working it through. Long live the champion of Jewish normalisation.

References

1.

הנורמליות אינה אלא פלורליזם עשיר ויצירתי שבה אדם ריבון למעשיו במידת האפשר ואופק אפשרויותיו גדול

- B. Yehoshua, Bizhut hanormaliut [For the sake of normalcy, 1980], Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: Schocken, 1984, p. 138, my translation. A less accurate version appears in Arnold Schwartz’s translation of this passage in Between Right and Right (NY: Doubleday, 1981), p.145.