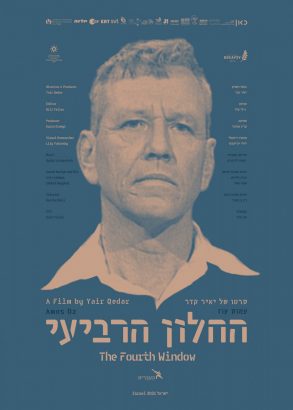

Liam Hoare says The Fourth Window, a new documentary about Amos Oz by the Israeli filmmaker Yair Qedar, is pessimistic and melancholic — more darkness than love.

Amos Oz stands upon the rooftop of his childhood home in the Jerusalem neighbourhood of Kerem Avraham, a place from which the world opened up to him. On a wet winter day, Oz is wrapped up against the cold as he steps around the junk and litter. ‘If a person becomes an author,’ he proffers, ‘it’s because he was wounded when he was a child. Without a wound, there is no author.’ Therein lies the subject of The Fourth Window, a new short but insightful biographical documentary by the Israeli filmmaker Yair Qedar: how literary triumph and personal tragedy shaped and defined Amos Oz’s life.

When Oz was 12-and-a-half, his mother Fania, a dreamy melancholic, took her own life. Oz was neither informed about the circumstances of her death nor permitted to go to her funeral, the victim of his father’s censorship. In The Fourth Window, Natalie Portman — who directed the 2015 film adaptation of Oz’s memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness — argues that Oz spent a literary career imagining the mind of his mother, that the act of becoming his mother was his way into literature. The Israeli scholar Nurith Gertz — whose 2020 work What Was Lost to Time documents her friendship with Oz — believes that without the death of his mother, Oz’s novels may never have been written.

Indeed, his childhood and his mother’s death is central to his prose. Again and again, Fania is brought back to life or given voice in one way or another in his stories: in the form of Hannah Gonen in My Michael (1968) or in his Jerusalem stories like The Hill of Evil Counsel (1976). ‘The truth is that I wrote My Michael almost under duress,’ Oz wrote in an introduction to the book. ‘The character of Hannah so overwhelmed me that I began speaking her idiom and dreaming her dreams at night.’ Unhappy families and parental loss, the mother-father-child triangle, only children and lonely children all feature prominently in his work, as do unmoored and malcontent characters.

Towards the end of his literary career, Oz produced a wonderful novel in the form of interwoven stories called Between Friends (2012), set on a kibbutz in the 1950s. What connected its vignettes were that its central characters were almost all outsiders in this closely-knit, claustrophobic society: orphaned children, restless young adults, and lonely, peculiar men. Oz is often thought of as the definitive insider: part of Israel’s secular Ashkenazi elite, spokesperson for the left and the peace movement, friend of Shimon Peres. But Qedar’s Oz is the perpetual outsider, a witness and observer from the time he abandoned Jerusalem for the kibbutz two years after his mother’s suicide.

When Oz showed up at Kibbutz Hulda, he was 14-and-a-half — the pale-skinned, skinny, and fragile son of a Jerusalem intellectual. ‘I was really homeless for a few years,’ Oz tells Gertz in a recorded phone conversation which gives The Fourth Window its structure. Because the kibbutz didn’t pay for clothing for children from the outside, ‘the years I was in Hulda, I wore the same clothes, the same underwear, the same socks, torn shoes. And if a button fell off, so be it.’ Until he met his future wife, Nili, Oz was alone on the kibbutz, an experience that Qedar believes fed into his particular kibbutz literature from Where the Jackals Howl (1965) to A Perfect Peace (1982).

Oz and his family left the kibbutz for Arad in 1985. ‘Before I got to the kibbutz, I thought that everyone loves everyone, so they will love me too. But once there, I quickly realised that not everyone loves everyone — they can’t,’ Oz tells Gertz. I know my children suffered on the kibbutz, he laments. ‘After what I went through as a child, why couldn’t I see what they were suffering? I can’t forgive myself for that.’ Oz was someone who was seen as a ‘secular prophet’ and a ‘moral marker,’ as Etgar Keret puts it. But as such, he ‘put enormous pressure on himself to be constantly good,’ moral, and just, Nicole Krauss says, and ‘that’s sometimes a very difficult thing for an artist.’

A little over two years after his death from cancer in December 2018, his youngest daughter, Galia, published a memoir, Something Disguised as Love, in which she accused her father of acts of verbal and physical abuse. The charges were first levelled not in public but in private, causing a schism in the family in the final years of Oz’s life. ‘He felt guilty,’ Gertz tells Qedar. ‘He said: I know I am to blame but I don’t know what for.’ ‘Galia, Galia. It’s this wound,’ Oz says to Gertz on the phone. ‘It’s a knife that’s not only stuck inside, it’s turning all the time. …I wrote her three or four long letters. I wrote: Galia, I am to blame for what I understand and also for what you didn’t explain and what I don’t understand. I accept it and ask for your forgiveness.’

While an unavoidable subject, Qedar is guilty of turning to the subject of Galia one too many times in The Fourth Window. The movie is a product of its time and the filmmaker can be said to have been chasing rather than making headlines, of being shaped by rather than shaping the world. Through interviews with Gertz and other scholars and critics of Hebrew literature, Qedar is adept at tracing Oz’s rise, the significance of his work in context, and the events and experiences in Jerusalem and on the kibbutz that formed him. It is after his first literary setback — damning reviews for 1987’s Black Box, a novel A.B. Yehoshua told Oz not to publish — that The Fourth Window loses a certain momentum and fades out.

Qedar’s portrait of Oz is a portrait of his wounds. The Fourth Window is pessimistic and melancholic — more darkness than love. In his conversations with Gertz, Oz reveals the doubts that racked him towards the end. He struggled to judge his worth in spite of the many accolades he had received. Oz says to himself rather starkly: ‘You are worthless as a person, you are worthless as a man, because the woman who meant the most to you,’ your mother, ‘left you and slammed the door.’ Oz believed he often failed to form meaningful connections with people and struggled with his final novel, Judas (2014). Interpretation can complicate a work of art and obscure it, but biography can also complete a novel in helping bring about an understanding of what brought it into being. The Fourth Window helps us see more of Amos Oz, and with it, more of his novels too.