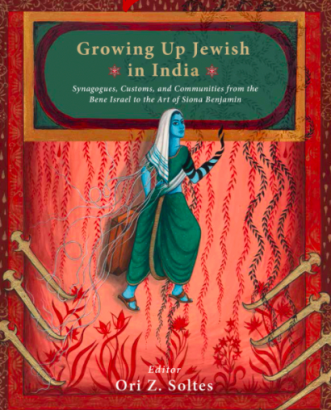

Growing up Jewish in India is a book about the Jews of India told from a variety of point of views – history, culture, art and religion. Ori Z. Soltes, the editor, teaches art history, theology, philosophy and political history at Georgetown University. He is interested in the ‘material culture’ of Indian Jews and offers powerful portraits of synagogues and communities over the centuries.

Siona Benjamin, and her miniature paintings, occupy much of the book. For Ori Soltes, her experience is ‘paradigmatic of the Jewish Indian experience,’ and her art ‘a complex and unique instrument of synthesis’ of that experience.

The Jewish experience in India was different in important ways from that of the Jews of the European-Christian and Muslim-Arab worlds. The absence of a religiously-sanctioned anti-Semitism was not the only unique aspect of the Indian Jewish experience. The ecosystem of Hinduism, especially ‘its embrace of diverse perspectives regarding how, specifically, one might understand and address divinity’, has meant that, more than other religious or traditional societies, Indian society has embraced multi-religiosity, inter-faith dialogue and cultural mixing.

The book examines the three major Jewish communities of India — the Bene Israel (in and around Mumbai), Baghdadi (from the city of Kolkata), and Cochini (from Southern state Kerala). Among India’s many minorities, Jews have been marginal in terms of numbers. There were no more than 20,000-30,000 Jews after India’s independence and, according to the latest census of 2011, just over 4,000 Jews remain in a country with a population of 1.2 billion. Most left after the 1950s for the newly established State of Israel.

This volume does not attend to the reasons for their aliya, focusing instead on their socio-cultural and historical evolution in the Indian subcontinent. The Jewish ethos of ’returning to the Holy Land’ and ‘ending the exile’ were driving forces for Jews who did not feel subjugated in India. They also moved in search of a better quality of life, economic opportunities, and marriages within the Jewish world.

Avi Nesher, the award-winning Israeli film-maker, captured in his movie Sof Ha’Olam Smola (Turn left at the end of the world, 2004) the personal dilemmas faced by an Indian Jewish couple that made aliya to Israel . The protagonist is an engineer in Mumbai who works in a milk bottle factory and has to live among the Mizrahi, Moroccan Jews, in a desert neighbourhood of southern Israel. He and his family feel let down by the socio-cultural marginalisation of the Jews of colour by the Ashkenazim.

The remaining Jews of India still conceive their identities as plural, identifying with ‘motherland’ India to ‘fatherland’ Israel as according to Prof. Soltes. The Indian Jews of Israel have mostly remained invisible in Israeli academia, civil society movements and politics, living quite apolitically in their ‘fatherland’ thus far.

The best take away from this book, which is beautifully designed and includes many paintings of Siona Benjamin, is the open-minded and truly multi-cultural worldview of not only the artist but also Indian Jews in general. Ori Soltes highlights the Indian way of life, the open-religion of Hinduism and values such as tolerance and acceptance of all. He also underlines the fact that Indian Jews might be the only group of Jews who do not carry unpleasant memories of ‘life in exile’.

Siona Benjamin lives in America now and is concerned about the way Israeli and American societies are growing more conservative and hence ceasing to be open to all identities. Through her art she wishes ‘to repair the world (Tikkun Olam) of its painful fractiousness and to bring its diverse human components together’. She proudly thanks India where she enjoyed truly multicultural society than anywhere else be it the United States ‘the leader of the free world’ or Israel the ‘holy land’.

Neither Benjamin or Soltes romanticise India. They are both aware of what has changed in Indian society and politics in the last three or four decades, in particular the growing power of religious nationalism. According to Soltes, ‘one of the unfortunate ironies for this story is that, in the present political dispensation in India, where Hindu nationalists are in power, India has, for the moment at least, ceased to be that country the long history of which shapes the context of this narrative with its magnificent tapestry of interwoven cultural, religious, and ethnic threads’. This may be too pessimstic. India’s syncretic culture has been through many ups and downs and current struggles against religious and cultural nationalism may yet preserve the Indianness of things. The epilogue sums up what that is. ‘[India is] open and in your face, it’s difficult and it’s amazing at the same time: full of colors, sounds, smells, tastes, and touches that assault all of the senses. India never hides; it is even shamefully blatant and revealing and unabashedly addresses our flawed, imperfect human existence. This is not for everyone—but richly rewarding and endlessly fascinating for those who embrace it—who embrace humanity—with all of our flaws and imperfections’.