For a half century, for good and for ill, Western universities have been incubating world views which go on to reshape mainstream opinion. Today’s global anti-Israel movement poses as a defender of internationalist values, but in practice demands a zero-sum solution based on creating a state of Palestine in place of Israel. It totally negates the national rights of Israeli Jews. It delegtimises the dialogue and compromise that could ensure national self-determination for both peoples as shameful ‘collaboration’ and ‘normalisation’. It is an obstacle to peace. Philip Mendes seeks one root of this self-righteous, destructive and polarising politics in the campus left’s simplistic ‘anti-imperialist’ response to the 1967 Six-Day War. The revolutionary left reduced a tragic, complex, and unresolved national question requiring deep mutual recognition and political compromise to a crude morality play, a stage on which to dress up and perform their radical identity.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a dedicated campaign spearheaded by the international Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) campaign to exclude moderate voices advancing recognition of the national rights of both Israeli and Palestinians peoples via a two-state solution from progressive publications and debates (Mendes 2018; 2019; 2021; Mendes & Dyrenfurth 2015; Nelson & Brahm 2015). That censorious campaign is based on an assumption that there can only be one legitimate progressive perspective on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: what is widely known as the one state view (which in my opinion should really be termed the ‘abolish Israel’ or pro-Greater Palestine position).

In the words of Susie Linfield, it demonises the Israelis as ‘the colonialist-racist-imperialist-fascist oppressor’, whilst the Palestinians in contrast are infantilised ‘as revolutionary-socialist-Marxist-Leninist-anti-imperialist freedom fighters’ (2019, p.5). Consequently, that imperialist and fascist state is framed as deserving of violent elimination.

That divide – between those who recognise the legitimacy of both Israeli and Palestinian claims to national self-determination, and those who seek to eliminate the right of Israeli Jews to statehood – is not new. As evidenced by the historical case study that follows, it has existed amongst progressives since the 1967 Six-Day War. The former view emphasises unlimited dialogue between the two peoples leading ideally to mutual compromise via a peacefully negotiated two-state solution. In contrast, the alternative path of boycott and confrontation favoured by the BDS movement seems likely to exacerbate existing conflict and violence, and further delay any prospect of statehood for the Palestinian people.

The drive to exclude the two-state perspective is a new development on the international Left, which has long been divided on the respective merits of Israeli Jewish and Palestinian Arab nationalism (Mendes 2014). It was the 1967 Six-Day War which drove a substantive shift amongst progressives from pro-Israel to pro-Palestinian sympathies (Linfield 2019; Mendes 2014). This transformation in attitude reflected both Israel’s emergence as a major military power which had conquered large areas of territory in the Sinai, Gaza Strip, West Bank and Gaza Strip, and particularly its occupation of more than one million Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza who were now identified for the first time as an independent national entity (Morris 2001; Oren 2002).

As Percy Cohen noted succinctly: ‘There can be no doubt that after 1967, the conventional wisdom of the New Left in America, as elsewhere, was that Israel was no longer a fairly progressive, socialist society in which collectivist pioneers had made the desert bloom, but was, instead, a minor imperialist power, racist in its ideology and an enemy of the poor, Arab peoples and of the “progressive” Arab states. As part of this new picture the heroic Fedayeen – seen as anti-imperialist, progressive, revolutionaries, to a man – were pitted against what were viewed as the militaristic, chauvinistic, tyrannical power of the CIA-backed Israeli military forces; Israel, clearly, was the agent of imperialism, while the Arabs, especially the Palestinian guerrillas, were part of the third world forces struggling for freedom and social revolution’ (1980, p.24).

Nevertheless, competing perspectives for or against two states or one state continued. In the article that follows, I examine this ideological heterogeneity via a case study of the range of progressive student opinions at Monash University from 1967-72, arguably the most radical Australian campus as reflected by its popular tag, the ‘Monash Soviet’. Even at Monash, there were three distinct perspectives on the political Left: a vigorous anti-Zionist view adopted by the Maoist-aligned Labor Club, a contrasting (critical and indeed socialist) pro-Israel stance presented by the Radical Zionist Alliance, and a moderate two-state position espoused by orthodox Communists. All three opinions were actively debated in the pages of the student publication, Lot’s Wife.

As was the case in many Western countries, Australian society in the late 1960s was subject to major generational revolt characterised by social, cultural and political ferment and protest. Much of the energy and militancy of the rising New Left student movement was directed against Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War, which was maintained by a selective conscription policy that resulted in the deaths of many young Australian males. Other targets of radical students included racism (against the Indigenous Aboriginal population at home) and abroad (particularly apartheid in South Africa), censorship, and repressive discipline policies within the university (Floyd & Mansell 2012; Mendes 1993).

In the words of Gordon & Osmond, the radical movement believed that inhumane policies within Australia and beyond were not the result of simple policy errors, but rather reflected ‘deeply ingrained value systems’ such as ‘racism, nationalism and chauvinism’. Hence, effective reform could only be achieved by forming an alliance of workers and students aimed at ‘combating these social and ideological structures’ (1970, p.30).

Monash University, ironically based in Melbourne’s very sedate south-east suburbs, was at the forefront of this movement often drawing comparisons with radical campuses internationally such as Berkeley and the Sorbonne. Most significantly, the Monash Labor Club was recognised as leading the ‘wave of radical thought and action’ in Australian student activism (Floyd & Mansell 2012, p.5). That club, increasingly influenced by Maoist ideology, elected to send funds to the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (known as the Viet Cong) which was directly engaged in a war with Australian soldiers. They also formed links with radical sections of the trade union movement via a group called the Worker-Student Alliance (Floyd & Mansell 2012; Wheatley 2021). If there was an Australian campus likely to advance a dogmatic pro-Palestinian perspective, it would have been Monash.

Three perspectives at Monash

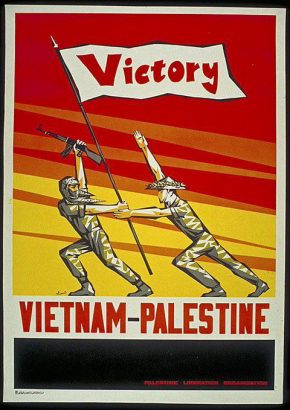

The propagandist slogan, ‘From Vietnam to Palestine: One fight, one enemy’ quickly became influential at Monash, appearing as a full page photograph in the student newspaper (Lot’s Wife, 14/9/70, p.9). Not surprisingly, the militant Monash Labor Club identified Israel as part of the American/Western bloc and the Arab states as aligned with the Third World bloc, and adopted a position urging an end to the State of Israel. As early as June 1969, prominent Labor Club leader and student revolutionary Albert Langer (who came from an upper middle class Jewish background), recommended that Israel be ‘dismantled’ because in his view the Jews unfairly ‘took over’ a country called Palestine that rightly belonged to the Arabs (Langer 1969). The Labor Club newsletter, Print, condemned an Israeli military raid on Egypt as an ineffective means to ‘stop Arab terrorism against Israel’ given that in their view most terrorism emanated from occupied Arab territories. They attacked the Israeli occupation of Arab territories as ‘based on the logic that the Arabs will negotiate and abandon their claims to the country that used to be theirs if the Israeli occupation is continued for a sufficient time’ (Print, 19/9/69).

The Labor Club claimed to support an internationalist position in the Middle East which rejected all forms of ‘exclusive’ nationalism, whether Arab or Jewish, in favour of the creation of a Socialist republic for all workers and oppressed peoples. Nevertheless, they specifically endorsed a ‘victory’ for the ‘Palestinian resistance’, which in their opinion would result in the creation of ‘a new multinational democratic Palestine in which Jews and Arabs share a common homeland’ (Print, 24/6/70). They seemed oblivious to the likelihood that this outcome would in fact erase the national rights of Jews. Yet this was at a time when the leading Palestinian nationalist group, Fatah, was unequivocally stating that any united state of Palestine would not be a ‘binational’ state, but rather an exclusively Arab state in which the Jews (or some Jews) would enjoy cultural and religious freedom, but no national rights (Achcar 2006, p.73).

Langer and his colleagues within the wider Worker-Student Alliance (WSA) actively participated in the Palestine-Australia Solidarity Committee (PASC) which was formed in 1971. PASC consisted of members of the Palestinian and Arab communities in Melbourne plus representatives from the Orthodox Communist Party of Australia, the Trotskyist Socialist Youth Alliance, the mainstream Australian Labor Party’s Socialist Left faction, and other radical Left groups. The WSA emphasised that ‘the enemy of the Palestinian and other Arab peoples is Zionism and not the Jewish people. Both the Jewish and Arab people of Palestine should live in an independent state of Palestine which will not be based on one race or religion’ (WSA 1971). Langer was one of the speakers at the first PASC public rally held in July 1971 (Percy 1971).

Other representatives of the radical Left espoused a hardline anti-Zionist perspective within the student newspaper. For example, an anti-Zionist Israeli Jew, Benjamin Merhav, aligned Palestinian nationalism with the international struggle against imperialism. Nevertheless, whilst asserting the primacy of Palestinian rights to national self-determination and demanding the abolition of Zionism, Merhav also insisted that Israeli Jews enjoy equal national rights within a binational state (Merhav 1969). A not dissimilar piece by PASC representative, Nassif Hadj, identified Zionism as an ‘anti-socialist and racist ideology’ associated with colonialism and imperialism. He argued that it was ‘the duty of every revolutionary socialist to condemn fully the Israeli Zionist state’ (Hadj 1971). Palestinian writer Ben Bela (1971) directly accused the Israelis of planning to exterminate the Palestinian population.

However, other left-wing groups and individuals at Monash University held more nuanced opinions on the Middle East conflict. An alternative progressive organisation was the Communist Club (formerly called the New Left Club) established mainly by students affiliated with the Communist Party of Australia (CPA). Although the CPA itself was divided on the Middle East conflict, this club firmly endorsed a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (Mendes 1993).

Additionally, the Radical Zionist Alliance (RZA) was formed by a group of left-wing Jewish students at Monash University, who were mostly graduates of Left Zionist youth groups such as Hashomer Hatzair and Habonim, to counter growing pro-Palestinian trends on the student Left. A number of them were also involved in the Communist Club. The RZA strongly defended Israel’s existence and attacked Arab national chauvinism (Mittleberg & Wolf 1970), but equally were very critical of the conservative views of official Zionist bodies within Australia. They urged a socialist ‘restructuring of economic and political institutions’ to transform Israel into a ‘collective economy operated democratically by the workers and kibbutz members’ (Zyngier & Blacher 1971). They also strongly opposed any plans by Israel to annex the occupied territories (Zyngier 1972).

The RZA sought to present a progressive form of Zionism, defining Zionism as ‘not an imperialist based colonialist philosophy, not a $50 once a year to Jewish National Fund philosophy, but a philosophy which once realised will allow the Jews to carry on the class struggle with all the other peoples of the world’. RZA urged mutual recognition of Palestinian and Israel national rights leading to the establishment of an ‘independent socialist Palestinian state existing alongside and coexisting with an independent socialist Jewish state’, and ‘opposed the reactionary tendencies of the Australian Jewish establishment’ (Blacher 1971). Additionally, the RZA were involved in broader left-wing campaigns such as the Vietnam War Moratorium Committee, and the anti-apartheid movement.

Nevertheless, the RZA faced the same challenge as other left-wing Jewish groups internationally seeking a two-state solution. There were no representative Palestinian groups within or beyond Australia at this time willing to ratify a political solution that respected the national rights of both Israelis and Palestinians. In fact, as RZA acknowledged, the contemporary Palestinian Liberation Organisation supported terrorist attacks against the Israeli civilian population as part of a strategy for the military destruction of the Zionist state of Israel (RZA 1972a; 1972b; Zyngier 1972).

Yet, the RZA’s political programme assumed that if Israel agreed to withdraw from the West Bank and Gaza Strip and negotiate a two-state solution, the Palestinians would welcome this development and accept an independent state alongside of, rather than in place of, Israel. According to the RZA, creation of a Palestinian state would ‘give Palestinian control over their own destiny. Palestine and Israel could thus have a relationship not predicated by oppression or repression of one by the other. Such a situation, though it would involve some dislocation, would remove the real cause of antagonisms between Jewish self-determination and Palestinian self-determination’ (RZA 1972a, p.9). But there was no verifiable evidence that this was the political solution that most Palestinians desired. One local Palestinian emphasised that their political concerns extended beyond the events of 1967 to those of 1948, and with securing national rights not only for Palestinians living inside the occupied territories, but also the much larger group of Palestinians residing as refugees in neighbouring Arab countries (Ben Bela 1971).

Most of the RZA’s activity seemed in fact to be directed at influencing the views of the Australian anti-Zionist Left, rather than Palestinians in Australia or elsewhere. They reasonably argued that the Left instead of attacking progressive Israelis should seek to reconcile Israeli and Palestinian nationalist agendas, and to promote a ‘dialogue’ between peace-seeking socialist groups within Israel and similar groups amongst the Palestinian Arabs (RZA 1972; Zyngier & Blacher 1971).

The appalling massacre of Israeli athletes by Arab terrorists at the Munich Olympics in September 1972 further divided the student Left. The WSA presented the following motion at a meeting of the activist Public Affairs Committee (PAC): ‘That this meeting unequivocally condemns the murder of members of the Israeli Olympic Team by individuals claiming to represent the Palestinian revolutionary movement. Further, that PAC believes that this attack and others like it are the inevitable product of the frustration and desperation bred by the dispossession and exploitation of the Palestinian people by the Israel, Jordanian and other Arab regimes. PAC believes that such attacks will end only when the land and rights robbed from the Palestinian people are restored to them’. However, that motion was rejected by a large Monash Association of Students meeting which unequivocally condemned the terrorist attack, and endorsed an overall, negotiated settlement to the Israeli-Arab conflict (Mendes 1993, p.117).

Conclusion

The anti-Zionist Left at Monash University represented in the Labor Club, despite claiming to be internationalists, framed the Middle East conflict in binary terms that demanded the privileging of the national rights of one group (Palestinian Arabs) over that of another group (Israeli Jews). They made no attempt to bring the two competing groups together to establish a dialogue that might identify some common political ground. In contrast, the moderate two-state advocates within the RZA argued that the international Left had a responsibility to promote respectful dialogue and conversations between Israelis and Palestinians that could potentially assist to reconcile their competing nationalist agendas.

That same division continues today. The BDS movement (echoing the Labor Club) poses as a defender of internationalist values, but in practice demands a zero sum solution based on creating a state of Palestine in place of Israel that would ensure optimal justice for Palestinians whilst totally negating the national rights of Israeli Jews. They oppose any forms of dialogue or negotiations (via what they pejoratively label ‘normalisation’) that would ensure national self-determination for both peoples.

In contrast, two-state advocates from moderate pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian perspectives (echoing the RZA) favour a win-win solution informed by mutual compromise and reconciliation that would result in partial justice including national statehood for both sides.

References

Achcar, Gilbert (2006) The Israeli Dilemma: A Debate Between Two Left-Wing Jews: Letters Between Marcel Liebman and Ralph Miliband. Merlin Press, Monmouth.

Ben Bela, Musstafa (1971) ‘Palestinians and the second invasion’, Lot’s Wife, 5 August.

Blacher, Yehuda (1971) ‘Radical Zionists’, On Guard, June: 7-8.

Cohen, Percy (1980) Jewish radicals and radical Jews. Academic Press, London.

Floyd, Emily & Mansell, Ken (2012) Disobedience: The University as a site of political potential. Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne.

Gordon, Richard & Osmond, Warren (1970) ‘An overview of the Australian New Left’ in Gordon, Richard (ed.) The Australian New Left: Critical essays and strategy. William Heinemann Australia, Melbourne: 3-39.

Hadj, Nassif (1971) ‘Zionism’, Lot’s Wife, 19 July.

Langer, Albert (1969) ‘Israel this land is my land’, Lot’s Wife, 10 June.

Linfield, Susie (2019) Zionism and the Left from Hannah Arendt to Noam Chomsky. Yale University Press, Yale.

Mendes, Philip (1993) The New Left, the Jews and the Vietnam War 1965-1972. Lazare Press, Melbourne.

Mendes, Philip (2014) Jews and the Left: The rise and fall of a political alliance. Palgrave MacMillan, Houndmills.

Mendes, Philip (2018) ‘Attempts to exclude pro-Israel views from progressive discourse: Some case studies from Australia’ in Pessin, Andrew & Ben-Atar, Doron (eds.) Anti-Zionism on campus: The university, free speech and BDS. Indiana University Press, Bloomington: 163-173.

Mendes, Philip (2019) ‘The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement and the poisoning of academic discourse: A case study of Henry Maitles on ‘The Left, anti-Semitism and Palestine’, Fathom Journal.

Mendes, Philip (2021) ‘The BDS movement in Australia: A case study’ in Kenedy, Robert; Rebhun, Uzi & Ehrlich, Carl (eds.) Critical Perspectives on Jewish Connectivity, Israeli-Diaspora Relations, and Antisemitism. Forthcoming.

Mendes, Philip & Dyrenfurth, Nick (2015) Boycotting Israel is Wrong: The progressive path to peace between Palestinians and Israelis. New South Press, Sydney.

Merhav, Benjamin (1970) ‘Arab rights in Palestine’, Lot’s Wife, 14 September.

Mittleberg, David & Wolf, John (1970) ‘Palestine and Jewish National Liberation’, Lot’s Wife, 21 July.

Morris, Benny (2001) Righteous Victims: A history of the Zionist-Arab conflict 1881-2001. Vintage Books, New York.

Nelson, Cary & Brahm, Gabriel Noah (2015), eds. The case against academic boycotts of Israel. Wayne State University Press, Chicago.

Oren, Michael (2002) Six Days of War: June 1967 and the making of the modern Middle East. Penguin Books, London.

Percy, John (1971) ‘Palestine Rally’, Direct Action, No.9, August.

Radical Zionist Alliance (1972a) Our Platform. RZA, Melbourne.

RZA (1972b) Arab-Israeli debate: Toward a Socialist solution. RZA, Melbourne.

Wheatley, Nadia (2021) ‘Albert Langer’ in Meredith Burgmann & Nadia Wheatley (eds.) Radicals: Remembering the Sixties. New South Press, Sydney, 83-101.

Worker-Student Alliance (1971) Palestine. WSA, Melbourne.

Zyngier, David (1972) ‘Middle East conflict’, Lot’s Wife, 16 October.

Zyngier, David & Blacher, Yehuda (1971) ‘Zionism a reply’, Lot’s Wife, 29 July.