The (four-time) failure of the right wing and ultra-Orthodox parties to garner 61 seats, the steady erosion of the taboo of Arab parties joining a coalition, and the internalisation within parts of the right that Netanyahu was being influenced by external considerations has led the country to a previously unimaginable scenario – a coalition spanning the nationalist right to the socialist left, and including the Islamists. But what now?

The unlikely resolution to Israel’s greatest political crisis since its establishment might be summed up by two iconic photos acting as dramatic bookends. The first, taken on election night in April 2019, shows Naftali Bennett and his erstwhile ally Ayelet Shaked walking down a corridor looking exhausted and downcast. It’s been a long night of vote counting, and their party, the New Right, is an agonising 1400 votes short of the electoral threshold. Their backs to the camera, Bennett and Shaked are out of the Knesset. Their political careers (as well as Netanyahu’s chances for a coalition) are seemingly shattered.

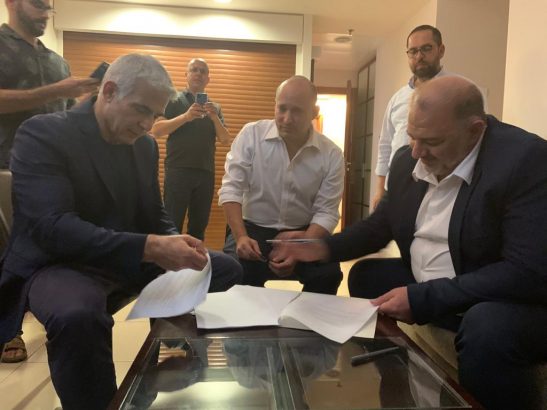

The second photo is from last week. In a scene almost unimaginable until it happened, Bennett sits alongside Yair Lapid and the leader of the Islamist Raam party Mansour Abbas, having signed a document for a rotating government in which Bennett will serve first as Prime Minister. His Yamina party only received 100,000 votes more than in April 2019 and one of the party’s MK subsequently refused to join the government. With the coalition set to win a razor thin Knesset vote of confidence in the next week, Bennett is set to stand at the top of Israel’s political pyramid. As comebacks go, it takes some beating.

The long journey from one photo to the other includes three additional elections, hundreds of hours of coalition negotiations, a global health crisis, a failed Prime Ministerial rotation agreement, and Benjamin Netanyahu breaking his word one too many times. It also includes other key junctures along the way: The (four-time) failure of the right wing and ultra-Orthodox parties to garner 61 seats; the steady erosion – initially for the Arab parties, then within the centre-left and ultimately on parts of the right wing – of the taboo of Arab parties joining a coalition; and the internalisation within parts of the right that Netanyahu was increasingly being influenced by external considerations – first and foremost his criminal trial for bribery, fraud and breach of trust.

In the spirit of Churchill’s remark that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried, the parties feel the coalition is the worst option…except for all the alternatives. Like many negotiations, the deep compromises made by all only happened when they felt they had no other choice.

Trinculo in Shakespeare’s Tempest says that misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows and so, of course does politics. This coalition was born out of misery with Benjamin Netanyahu, who is still desperately trying to split off more Yamina MKs or hoping that some deus ex machina will tear apart the nascent coalition and save his premiership. For all his perceived political magic, no one bar Netanyahu could have midwifed an opposing coalition spanning Yamina and New Hope on the right to Labour and Meretz on the left, and ably supported by the Islamists of Raam. Such bedfellows were never envisaged by political experts. Even today it seems difficult to believe.

Critics of Bennett charge him with collaborating – yes that’s the word they use – with ‘leftists’ and Israel’s enemies. Indeed, Netanyahu’s acolytes have long accused anyone opposing their leader as being a ‘leftist’, while conveniently forgetting Netanyahu himself engaged Raam and had in the past often included left-wing coalition partners when necessary. Others point to Bennett’s vow he wouldn’t sit in a coalition with Lapid as Prime Minister (a scenario due to happen in two years under the rotation agreement). But Bennett made other commitments too. First and foremost was to prevent a fifth round of elections. Another was to replace Netanyahu. Coalitional mathematics and Netanyahu’s refusal to step aside for another Likud MK meant keeping all these promises was impossible. Supporters may feel that, in the current political conundrum, becoming Prime Minister and preventing new elections isn’t a bad deal.

But what does the coalition of change (or coalition of hate as its detractors call it) have in common? Discussions over Palestinian statehood or West Bank withdrawal – hardly a hot topic anyway in the election cycles – will be frozen (or so they hope – the Palestinians may have other ideas). But the battle against Iran will continue unhindered. Relations with the Biden Administration – unencumbered by Netanyahu’s history of perceived Trumpism, partisanship, and toxicity amongst Democrats – could even improve.

Priorities will undoubtedly be in the economic realm. Israel’s deficit of 11.7 per cent of GDP is its highest since the mid-1980’s, with experts believing it will take years to return it to pre-Corona levels. The country has been budget-less for over two years and senior civil service positions are unfilled. When Lapid talks about a return to sanity he means dealing with these things, as well as a political culture in which opposing MKs are often seen as enemies (or existential threats). It may not seem overly ambitious, but many Israelis would be grateful if the government made progress on these issues.

The biggest dangers to the nascent government come from two sources. The first mirrors what former British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan allegedly told a journalist he most feared – events. Terror attacks, a return to internecine violence within Israel, escalation in Gaza or a dozen other potential crises could tear the government apart.

The second danger comes from Netanyahu himself. As head of the opposition, he will seek to make the government’s life hell. No stranger to using popular disillusionment to undermine sitting governments – having successfully done it to Messrs Rabin, Peres and Olmert – Netanyahu’s experience, combined with the frenzied army of supporters who believe the new coalition is the equivalent to a coup, and the poison facilitated by social media could be perilous for Bennett and Co.

Yet Bennett, Lapid and the others need each other. Were the government to prematurely collapse and fifth elections called, many parties would be decimated. The right wingers, Bennett’s Yamina and Gideon Saar’s New Hope, would likely fare the worst – they need time governing to strengthen their credentials. Lapid, who painstakingly put the coalition together, also wants time – in two years he could become Prime Minister. So too Meretz, tasting their first ministerial positions in two decades. Let’s not forget Mansour Abbas, whose future political career may depend on how much benefit he can bring the Arab community.

Ironically, it might be Netanyahu’s absence that could pose the gravest threat to the coalition. His court case (which he initially wasn’t forced to attend by virtue of being Prime Minister) will continue, perhaps even speed up. Separated from the corridors of power, he will likely face a leadership challenge from within Likud. Yet Netanyahu’s complete removal from the political scene in Israel would simultaneously eliminate a major raison d’etre of the Bennett-Lapid government. With a new Likud leader, and Bennett’s two-year rotation deal approaching an end, the dream of a right wing/ultra-Orthodox coalition could be reignited.

What might happen then is anyone’s guess. In any event, it certainly wouldn’t be the biggest twist or turn of the last three years. That happened last week.