At the beginning of January 1949, eight months after Britain had withdrawn from Palestine, Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin issued an ultimatum to Israel: unless she immediately withdrew her forces from Egyptian territory, Britain and Israel would be at war. Barely three weeks later Bevin had agreed to the de-facto recognition of the Jewish State. Ronnie Fraser investigates the Labour government’s volte face.

Introduction

At the end of the Second World War Great Britain was the dominant military and political power in the Middle East. Not only did she hold the UN mandates for Palestine and Trans-Jordan but she was also very influential in the former French mandated areas of Syria and Lebanon. In addition, the leading independent states in the region, Egypt and Iraq, had signed military alliances with Britain. The only exceptions in the region were Saudi Arabia, where American influence was growing, and Iran which Britain had jointly occupied with Russia since 1941.

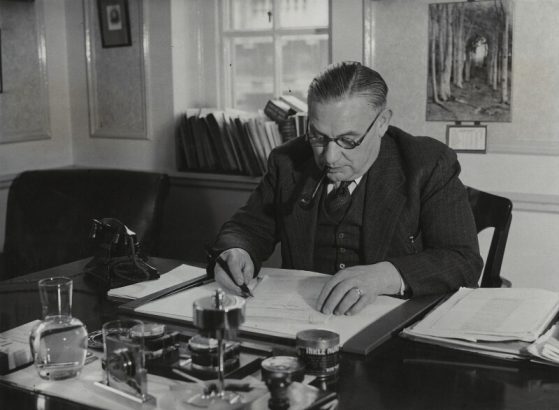

Ernest Bevin was appointed Foreign Secretary by Prime Minister Clement Attlee after the Labour Party won the 1945 general election. He held the post for nearly six years and his achievements included the creation of NATO and the Federal Republic of Germany. He was instrumental in ensuring Stalin was held in check in Germany and kept out of Western Europe. Bevin also established Britain’s ‘special relationship’ with the America, but disagreed with Truman, the American President over the future of Palestine, which was one of Bevin’s few failures.

Bevin was an Imperialist at heart and his approach to the problems of the Middle East in 1945 was to seek the friendship of the Arab world because he believed that British influence in the region was critical to the safeguarding of Britain’s links with her Empire and her future prosperity. Bevin was such a strong character that Britain’s Middle East policy was decided by him and no one else. He opposed the creation of a Jewish State in Palestine because he was convinced it would have a damaging effect on relations with the Muslims in the Middle East and India as well as affecting Britain’s extensive interests in the region. Just like he had in Europe, Bevin opposed Soviet expansion into the Mediterranean and the Middle East but he also feared that Jewish emigration from Eastern Europe into Palestine could turn Israel into a Soviet ally.

As a successful trade union negotiator, Bevin had expected to be able to negotiate a settlement between the Jews and the Arabs but after two years of trying he gave up and Britain returned the mandate to the UN in 1948 which resulted in the State of Israel being declared on 15 May 1948. The new state was immediately plunged into a fight for survival with the surrounding Arab States. Bevin continued to frustrate Jewish ambitions, withholding recognition of Israel until its borders were settled and refusing to support Israel’s application for membership of the United Nations.

At the beginning of January 1949, eight months after British had withdrawn from Palestine, Bevin issued an ultimatum to Israel: unless she immediately withdrew her forces from Egyptian territory, Britain and Israel would be at war. Yet barely three weeks later Bevin had agreed to the de-facto recognition of the Jewish State. This essay will investigate this volte face.

Prologue

In January 1947 Bevin and Emanuel Shinwell; the Minister of Fuel and Power, who was Jewish, presented to their colleagues in the Cabinet a secret memorandum, ‘Middle East Oil’, in which they outlined the vital importance for Britain, and her Empire, of the oil resources in the Middle East. They predicted that by 1950 ‘the ‘centre of gravity’ would have shifted from Iran ‘to the Arab lands’ with Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait and Iraq being the main producers in the region. Bevin warned his cabinet colleagues of the serious risks involved in offending the Arabs ‘by appearing to encourage Jewish settlement and to endorse the Jewish aspiration for a separate State’.[1]

The report of the United Nations Special committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) in September 1947 recommended that Palestine be partitioned into a Jewish State and an Arab State. Bevin opposed the partition of Palestine because he believed it would lead to an Arab uprising which would alienate the Arab States at a time when British policy was based on building relations with those states. He was determined that Britain should not be seen to be implementing such a policy, or be implicated with it in any way. He said that such a decision would ‘contribute to the elimination of British influence from the vast Muslim area between Greece and India’ and would ‘jeopardize the security of our interests in the increasingly important oil production in the Middle East’.

It was therefore not surprising that as a consequence of his outright opposition to the establishment of a Jewish State, and to the unlimited immigration of Jewish refugees into Palestine, that Bevin was perceived by many Jews to be an antisemite. He and Prime Minister Clement Attlee, were thought to have betrayed the promise of the Balfour Declaration, which the Labour Party had consistently supported until Attlee’s Party won the 1945 general election.

The Royal Air Force’s involvement in the Arab–Israeli conflict after May 1948

Israel’s war of independence with the Arab states lasted from May 1948 until the spring of the following year. Egypt was the first Arab state to agree a ceasefire, in January 1949. In order to implement Bevin’s policy of friendship towards the Arab states Britain continued to monitor events in the Arab–Israel war. The RAF did not leave Palestine on 14 May, remaining behind in order to cover the final withdrawal of British Forces. The following day, Egyptian Air Force Spitfires attacked Tel Aviv and Sde Dov Airfield. One of the Egyptian Spitfires which was brought down by ground fire was salvaged by the Israelis and later used by the Israeli Air Force. On 22 May, Egyptian Air Force Spitfires attacked Ramat David Airfield, where the RAF was still in occupation, destroying five RAF Spitfires on the ground and killing four airmen. The Egyptians apologised for the ‘unfortunate incident’ by claiming that they thought the airfield had been taken over by the Israelis. A few days later the RAF left Palestine and the five remaining squadrons were transferred to the Canal Zone, Aden and Trans-Jordan.[2]

Fighting between the Arabs and the Jews began in November 1947 after the United Nations voted for partition. The Jews who were attempting to purchase weapons from overseas for their armed forces received a setback when the United States suspended all arm shipments to the Middle East in support of the UN arms embargo. The British were overjoyed with this decision as it meant that the Jewish forces would be at a serious military disadvantage whilst the embargo would not affect the armies of Egypt, Iraq and Trans-Jordan who had been armed and trained by the British. The Yishuv faced two major challenges in establishing an air force: locating aeroplanes and hiring aircrew. Whilst their arms and aircraft buying efforts made newspaper headlines throughout the world, they recruited volunteer pilots, aircrew and mechanics, many of whom were World War two veterans. By the autumn of 1948 the Israeli air force had nearly 100 aircraft including twenty-five fighter aircraft.[3]

Many Israelis felt that the British Forces based in the Suez Canal Zone were assisting the Egyptian army and air force and sharing intelligence with the Egyptians. They had similar concerns about the Jordanian Arab Legion, which had been established and trained by Britain who took part in several battles against the Israeli armed forces during the conflict.

The RAF which had been tasked by the British Government to monitor developments in the region undertook regular overflights of several Middle East countries, including Trans-Jordan and Palestine using De Havilland Mosquito photo-reconnaissance aircraft which were based at the RAF airfield in the Suez Canal Zone. These missions enabled Britain to monitor the progress of the war.

The RAF were making almost daily reconnaissance flights over Israel and were flying too high for the Israeli Airforce to intercept them until 20 November 1948, when white contrails were once again sighted over the Galilee heading south. The Israeli Air Force responded by scrambling one of its two P-51 Mustang fighter aeroplanes that had recently been re-assembled following their arrival from the USA. These almost daily flights over Israel had become routine, giving the RAF a false sense of security. The RAF was unaware that the Israeli Air Force now possessed an aeroplane capable of intercepting their high-flying aircraft. The Mosquito crew failed to spot the Mustang until it was too late. The pilot of the Mustang opened fire on the unarmed RAF Mosquito which exploded and crashed into the sea off Ashdod, killing the crew of two.

On 16 December, The Times Newspaper reported that an Israeli army spokesman had refused to confirm the nationality of a Mosquito aircraft which had been shot down over Israeli territory on 20 November. He said that the downed airplane was believed to be an enemy aircraft because no Israeli Mosquito had been in the air at that time; and the Israelis had not received notification from any country that one of its aircraft would be flying over Israeli territory. The spokesman added that Mosquito aeroplanes had been making reconnaissance flights almost every day for the past three weeks and that any aeroplanes which did not belong to Israel and were flying over Israeli territory while a state of war existed were assumed to have hostile intentions.[4]

On the same day Mr. Henderson, Secretary of State for Air, told the House of Commons that the RAF Mosquito which had been shot down was an unarmed machine on a ‘training flight’ and that the matter had been taken up with the United Nations Mediator. The Secretary of State was unable to say why that flight had been undertaken over what Mr Churchill had described as a ‘very dangerous and delicate area.’[5]

The British Government subsequently admitted that these high level reconnaissance flights, had been authorised by the RAF Commander-in-Chief (CIC) in the Middle East, and had been carried out since the end of the Second World War as part of their peace-time operational ‘training programme’.[6] No ministerial approval had ever been sought for these overflights and further overflights had been suspended until the appropriate ministerial approval had been obtained. After British troops had been evacuated from Palestine in May 1948 no fresh directives had been given to the Commanders in the Middle East. Discretion continued to be left with the Commander-in-Chief (CIC) in the Middle East, as it had been when Palestine was a British mandate. Nor had the Minister told Parliament that these flights had been taking place. The intelligence gathered from these missions was used to update a plan which the cabinet discussed in November 1947 which envisaged Britain going to the aid of Trans-Jordan under the terms of the Anglo-Trans-Jordan Treaty. The British Government became concerned because the Israelis appeared to be gaining the upper hand in the war. They feared that, with the Arab Legion poorly-equipped, the RAF base near Amman would be vulnerable to an attack if Israel decided to invade Trans-Jordan. Britain’s official explanation for these flights was that since the Security Council truce in June 1948 and the placing of a complete embargo on the supply of military materials to Palestine and all the Arab countries, these flights had continued in order to ascertain any breaches of the truce by either side.

As Britain had not yet recognised the State of Israel, the Government used in its official statements terms such as ‘the Jewish authorities’ or ‘Jewish aircraft’ when referring to Israel’s Government or its armed forces whilst continuing to describe the country as ‘Palestine’.

Bevin’s Ultimatum

Bevin’s justified the resumption of daily reconnaissance flights on 30 December on the grounds that he had received reports that ‘Jewish’ forces had crossed into Egyptian territory and this raised serious questions with regard to Britain’s treaty obligations with Egypt and her vital interests in the Middle East. He considered the flights necessary because UN observers had been prevented by the ‘Jewish authorities’ from moving to the front and Britain had to obtain independent confirmation of the extent of the ‘Jewish’ incursion into Egypt.[7]

Britain had not been asked by the United Nations or any other country asked to carry out these flights. The former UN mediator, Count Bernadotte, had been aware of the flights but his successor, Dr Bunche, was not. Although the decision to send these flights was the British Government’s, they shared the information gained with the United States Government, who were aware of how the information had been obtained.[8] The Israelis, who viewed the British overflights as the continuation of Britain’s opposition to the existence of a Jewish State, were not aware of Britain’s limited intelligence collaboration with Egypt.

The RAF reconnaissance flight on 30 December established that Israeli forces were approximately seventeen miles inside Egyptian territory. This was confirmed by subsequent reconnaissance flights on the 1st, 2nd and 4th January. At this point Bevin feared that the Egyptian Army in Sinai were on the verge of defeat and told the Americans that Britain would intervene under the terms of the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty unless Israel withdrew her forces from the Sinai. Washington then presented the British ultimatum to the Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion who, rather than go to war with Britain, ordered his forces to withdraw from Egyptian territory.

As the Israelis were now unable to press home their advantage in the Sinai they turned their attention instead on the remaining Egyptian forces in the Gaza Strip. On 3 January 1949 the Israelis launched an attack on the Egyptian Army at Rafah. After three days of fighting, the Egyptian forces were close to defeat, so the Egyptian government announced that it was willing to enter armistice discussions if the Israelis agreed to a ceasefire. On 7 January, Israel agreed to a ceasefire.

The RAF continued to follow existing orders and a reconnaissance flight on 6 January revealed a fresh Israeli incursion into Egyptian territory. The details of ceasefire which was due to come into force at 1600 hrs the following day were only received by the British Canal Zone forces on 8 January.

On the morning of 7 January the RAF sent two reconnaissance missions over the combat zones around Rafah, the first, a high level photographic reconnaissance by one Mosquito escorted by four Hawker Tempests took place without incident. The second mission of four Spitfires was to provide ‘tactical reconnaissance’. The pilots were instructed not to cross into Israeli territory or to attack Israeli ground or aircraft and were only permitted to return fire if attacked. Just before noon the four Spitfires flew over an Israeli convoy which had been attacked fifteen minutes earlier by five Egyptian Air Force Spitfires. The pilots had spotted burning vehicles, and when two planes dived towards the convoy to take photographs, Israeli soldiers on the ground opened fire with machine guns and one Spitfire was shot down. Within seconds the remaining three RAF Spitfires were shot down by a pair of Israeli Spitfires patrolling the area. One of the British pilots was killed, two were captured by the Israelis and the fourth was rescued by Bedouin Arabs who returned him to his base. At the start of the battle the Israelis were not sure whether the Spitfires belonged to the Egyptian Air Force or the RAF, as all four aeroplanes had been shot down on the Egyptian side of the border.

Once the RAF realised that their four Spitfires were missing they sent a further patrol of fifteen Tempests and four Spitfires to find the missing planes. The RAF Tempest pilots were concentrating on searching the ground for wrecked aircraft when they were attacked by a patrol of four Israeli Spitfires. The majority of the Tempests were unable to defend themselves as their guns had not been primed for use before take-off. A number of Tempests were hit and one crashed ten miles inside Israel killing the pilot.

The Israeli government immediately sent a message to London via the UN saying that it had no intention of attacking Britain. The IDF however prepared for a British revenge attack as they assumed that the RAF would not allow the loss of five of their planes to go without retaliation. However, permission for a retaliatory strike was refused, though the RAF was told to view any Israeli planes flying over Egyptian territory as hostile.

The British Government were very angry at what had happened and the Cabinet decided to put all British Forces in the Middle East on full alert. As a first step to implement the plan that had been agreed in November, they sent a British force to the Red Sea port of Akaba. This was explained as a precautionary measure because of the grave concern with which they viewed the ‘Palestine’ situation. A memorandum was prepared which stated that the British Government took a grave view of the events which had resulted in the loss of five British aircraft as a result of unprovoked attacks by ‘Jewish’ aircraft over Egyptian territory. The British also informed the UN acting mediator of these events, making clear their intention to make a strong protest to the ‘Jewish’ authorities at Tel Aviv while reserving their rights with regard to claims for compensation and to all possible subsequent action.[9]

On 10 January The Times reported that the memorandum protesting against the attacks had been delivered by Mr Cyril Marriott, the Consul-General in Haifa, who promised to forward the documents to Tel Aviv immediately. The British Government’s original plan had been to deliver their protest to the Israeli Government’s acting representative at United Nations in New York but it had failed because the British addressed their protest ‘to the Jewish authorities in Tel Aviv.’ Mr. Lourie, Israel’s acting representative at the UN informed Sir Terence Shone, the British delegate to the Security Council that he had no authority to forward any communications not addressed to the Government of Israel.[10]

The Times wrote that ‘Israel will probably complain that Britain is in breach of the Security Council’s truce resolution of May 29 last, forbidding the introduction of fighting personnel into the Middle East. It is scarcely for Israel to complain of non-observance of Security Council resolutions; but in any case the resolution was addressed to countries taking part in the Palestine conflict, which do not include Great Britain.’ [11]

British Retreat

There was no support for the British Government from either the American Government or the British public. President Truman strongly criticised the RAF flights over the battle zone and the landing of troops at Aqaba, while praising Israel’s prompt withdrawal from the Sinai and its willingness to enter armistice negotiations. The British public and media wanted to know what RAF planes were doing over Israeli territory and why Britain threatening to go war against the Jews in order to aid the Egyptians. The Guardian newspaper commented that ‘Mr Bevin’s policy is taking perilous and needless risks in the Middle East, He must understand that the people of this country recoil from the idea of an attack on Israel and have no patience with any gestures, which carry the threat of an attack or their sanction.’[12]

On 19 January when Mr Henderson made a statement in Parliament on the shooting down of five RAF aircraft by Israeli forces he was closely questioned by Winston Churchill who demanded to know who had taken the decision to go ahead with the flights and whether the Minister had acted on the instructions from the Foreign Office. Clement Attlee, the Prime Minister was forced to intervene and said that ‘The action taken is the action of the Government. The Government are responsible; I am responsible; the Government are prepared to answer for their actions’ [13]

The following week during a Parliamentary debate on Palestine, Bevin came close to admitting defeat when he said that the Government’s policy had been ‘to persuade Jews and Arabs to live together in one State as the Mandate charged us to do. We failed in this. The State of Israel is now a fact’ adding that ‘we have not tried to undo it.’ In fact, Bevin had opposed the creation of a Jewish state every step of the way, especially at the UN, and had blocked the unlimited immigration of Jewish refugees into Palestine. Bevin told the house that if the Palestine war resumed it be ‘impossible’ for Britain to remain ‘indifferent and inactive’. However, the Foreign Secretary did not use the opportunity to announce British de facto recognition of the Israeli Government.

Churchill charged Bevin with being prejudiced against the Jews of Palestine. ‘The Foreign Secretary,’ he said, ‘was wrong, wrong in his facts, wrong in the mood, wrong in the method and wrong in the result’ adding that ‘We have lost the friendship of the Palestine Jews for the time being’.[14]

The Guardian wrote about the debate ‘that the British Government has still not recognised the State of Israel. That is the one hard fact which stands out of Mr. Bevin’s speech … recognition will come now so late, so reluctantly, so churlishly that it will pass almost unnoticed. What might once have roused hearts and won friends becomes at last an almost empty gesture…’[15]

Ironically, the shooting down of five RAF aircraft by Israeli Spitfires, which could have led to British military intervention, led instead to Bevin releasing the remaining Jews who were still interned on Cyprus. Three days later, on 29 January 1949, the British announced de facto recognition of the State of Israel.[16]

Palestine was one of Bevin’s few failures. The deaths of the four RAF aircrew could have been avoided. The Spitfire pilots died because the Government failed to tell the RAF in CIC Middle East of the impending ceasefire. The Mosquito crew died because the British intelligence services either didn’t know or failed to tell the RAF that the Israeli Air Force had acquired Mustang fighter planes. Although Atlee was Prime Minister, he allowed Bevin to decide and implement the Government’s foreign policy. Bevin was thus effectively the acting Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces in the Canal Zone and was ultimately responsible for their deaths.

References

[1] Martin Gilbert, Israel: A History, Doubleday, London, 1998, pp.141-2.

[2] http://britains-smallwars.com/campaigns/palestine/page.php?art_url=raf

[3] The Israeli Air Force was officially formed on 28 May 1948.

[4] ‘Shooting down a Mosquito, Israeli Explanation’, The Times, 16 December 1948.

[5] ‘Statement in the Commons’, The Times, 17 December 1948.

[6] Hansard, 19 January 1949.

[7] ‘Authority for RAF flights near Palestine border Minister closely questioned’, The Times, 20 January 1949.

[8] The Minister subsequently told the House of Commons that twenty reconnaissance flights which had passed over Palestine had taken place in December and January, but none of them flew exclusively over territory in Palestine occupied by Jewish forces.

[9] ‘British Protest to Israel-Grave view of shooting down of RAF aircraft’, The Times, 10 January 1949.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] The Guardian, 10 January 1949.

[13] Hansard 19 January 1949.

[14] Ibid.

[15] ‘Palestine’, the Guardian, 27 January 1949.

[16] For details of when Britain recognised the State of Israel: Ronnie Fraser, ‘The “Antisemite Ernest Bevin” and the day Britain recognised the State of Israel’, Fathom Journal, July 2020.