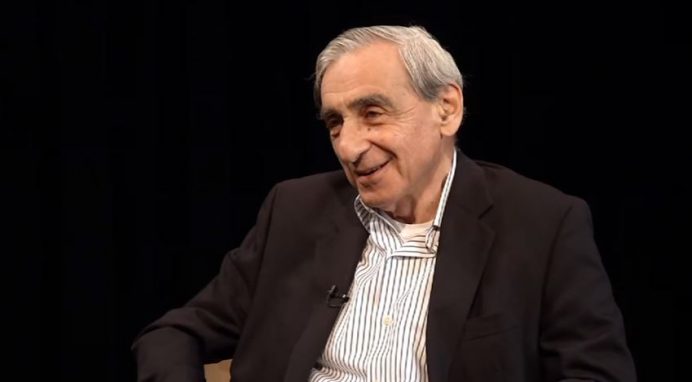

Michael Walzer is professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey and editor emeritus of the democratic socialist journal Dissent. He explains why he, a signatory of the Jerusalem Declaration, is urging UCL faculty and staff to defend the IHRA.

As I wrote in my previous piece in Fathom, my reasons for signing the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism (JDA) had to do with my own experience of fighting against anti-Zionism in the American academy. Now friends in Great Britain have reminded me of my commitment to particularity, to the importance of local circumstance. A political position, they rightly say, that fits one time and place may not fit another. I don’t think that they agree with my position here, but I agree that I need to think about their position there — specifically at University College London (UCL) where the controversy about defining antisemitism has reached a critical stage.

I have talked with people who teach in UCL, and I have read students’ accounts of their everyday life on the campus (and on other British campuses). The students describe an atmosphere that is unlike anything I have experienced myself and far more nasty than anything I have read about on any American campus. Jewish students are regularly denounced with the Zionist-Nazi trope and harassed and bullied as they go about their academic routines in ways designed to isolate and intimidate them. They say further that they need the IHRA definition of antisemitism so that they can give their treatment its proper name.

As I understand it, IHRA is a non-legally binding working definition of antisemitism; it has been adopted at UCL, and there is now an effort to rescind the adoption. What is at issue here is not the enforcement of this or any definition; it is not a question of regulating or censoring research or teaching. IHRA hasn’t been incorporated into UCL’s disciplinary code, and no-one has proposed that it should be. Arguments about Israeli wickedness would not be constrained, though if they reach a certain level of viciousness, I hope they would be called out. What is actually at issue is the recognition of antisemitism as an everyday feature of campus life. The people arguing against IHRA (I have read them, too) do not seem to understand the urgency of the fight against the bullying and harassment of Jewish students.

In the US, I thought that IHRA prompted the wrong question — not ‘What’s wrong with this anti-Zionist argument?’ but rather ‘Is this antisemitism?’ In Britain, I have come to think, the second question is very often the right one. And of that’s so, rescinding IHRA or replacing it with a definition perceived as more permissive, would send a very bad message to students and teachers at British universities. It would be a license not only to treat the State of Israel as the embodiment of evil (I would be happy to join an argument about that) but to treat every Jewish kid as an agent of evil — which no university should allow. So I hope that UCL faculty and staff will defend IHRA, as I would do were I with them.