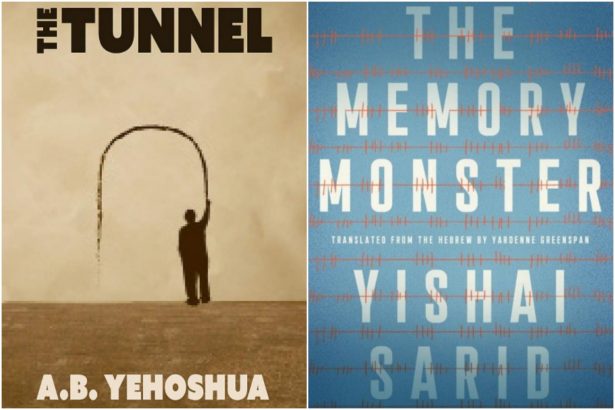

Two Israeli novels — The Memory Monster by Yishai Sarid and The Tunnel by A.B. Yehoshua — made it onto the New York Times’ list of 100 notable books in 2020. Gal Beckerman called Yishai Sarid’s The Memory Monster (first published in Hebrew in 2017) ‘a brilliant short novel that serves as a brave, sharp-toothed brief against letting the past devour the present.’ Writing of A.B. Yehoshua’s The Tunnel (Hebrew in 2018), Peter Orner said he found ‘great beauty’ in a work which grapples with one’s couple experience of dementia and the realisation that from the initial diagnosis on, ‘everything is going to be different.’ Both novels are in their own ways compelling and represent confrontations with the subject of memory: collective in Sarid’s case; individual in Yehoshua’s.

The son of the conscience of the Israeli left, the former education minister and Meretz leader Yossi Sarid, Yishai Sarid’s novella takes the form of a report written to the chairman of the board of Yad Vashem. Its author is a Holocaust researcher who specialises in methods of killing and, in a bid to give his family a more secure life than that which a low-level academic can provide, ‘harnesse[s] himself to the memory chariot’ and takes his expertise to Poland where he leads groups of Israeli schoolchildren around the country’s metropolises of death. The report’s subject is one man’s downfall—how the titular memory monster ‘bit into [his] flesh.’

The Memory Monster is a powerful examination of what becoming an ‘official representative of memory,’ as the report’s author styles himself, does to a person — how the Holocaust can consume and destroy a human being. Rather quickly, the author becomes strangely comfortable in Poland. The sites of the Holocaust become oddly familiar; ‘I almost felt at home,’ he writes. The closer Sarid’s protagonist is drawn to the subject, the more perverse his relationship to it becomes. ‘And one last thing, which has slowly permeated me over the years, is the invisible admiration of the murder; the decisiveness and ruthlessness, the audacity, the final, focused, and cruel act, after which there is nothing but silence.’ That which once moved the author on his first trips to Poland becomes sterile; naivety turns to cynicism.

Pushed and pulled between his family in Israel and work in Poland, the latter begins to infect the former. When his son has problems with another boy at kindergarten, the author shows up on the playground, towers over the young bully, and shouts, ‘Don’t you dare touch my son!’ ‘Force is the only way to resist force, and one must be prepared to kill,’ he writes. The Holocaust has a kind of gravitational pull from which the author cannot escape. He becomes addicted to its images. He scolds himself for becoming so transfixed by its facts. He begins to feel possessive of Holocaust memory — not merely its guardian but its owner. The protagonist becomes one sacrifice to the memory monster.

But he is not the only one. Sarid’s novel also asks what Holocaust memory has done to Israelis themselves. The report’s author worries that the Israeli flag and national anthem have become a coping mechanism devoid of meaning for young visitors to the camps and that, for the religious children he guides, the Holocaust has become conceived of as a ‘divine decree,’ a story within which the murderers and their agency barely register. He struggles to connect with the pupils he shows around Auschwitz and Majdanek and distrusts the emotions they project, in part because he hears what the kids say to each other when they think he isn’t listening—that, to quote one of them, ‘in order to survive we need to be a little bit Nazi, too.’

Beckerman’s review in the New York Times was glowing and yet it is also possible he was understating things. The Memory Monster is one of the great Israeli novels to have been published in translation in recent years. Sarid’s book is wonderfully subversive, darkly humorous; riveting, challenging, and thought-provoking. The voice — captured well in English by Yardenne Greenspan—is finely balanced, teetering on the edge as the memory monster sinks its teeth deeper and deeper into Sarid’s protagonist. The Memory Monster is a novel that demands to be read and deserves our attention. It is the first of Sarid’s novels to be translated into English, and I hope, not the last.

The Memory Monster and The Tunnel share not merely the subject of memory and but also a common focus on the decline of a central protagonist. The latter, however, is written in an entirely different register. A.B. Yehoshua—whose novels like A Late Divorce (1982) and Mr Mani (1990) were part of a generational transformation of Hebrew literature — has, writing in his early 80s, turned his attention to the subject of dementia. In his new book’s opening scene, Zvi Luria, a former engineer at the Israel Roads Authority, learns of the atrophy in his frontal lobe indicating mild degeneration, the black hole that is consuming first names and will soon suck in other fragments of his memory.

Artfully translated by Stuart Schoffman, the finest sections of The Tunnel are those which track Zvi’s slow degeneration, a decline of which, as is often terrifyingly the case, he himself is conscious. Not only names but numbers and places, a certain sense of place and self, are eaten up by the atrophy in his cerebral cortex. Zvi picks up the wrong boy when he goes to collect his grandson from school; trips to the supermarket and the opera become calamitous. In these moments, Yehoshua is attentive to the minutiae of everyday life and the small incidents that, gathered together, make up the tragedy of dementia.

Zvi’s doctor urges him to return to work. As the behest of his wife, he becomes attached to a young engineer at the Israel Roads Authority, an unpaid assistant on a tunnelling project in the Negev, a development which gives the novel its thrust. In describing the Martin Amis novel Yellow Dog (2003), Bookworm host Michael Silverblatt said rather brilliantly that it reminded him of ‘a board game whose rules are missing.’ The experience of reading The Tunnel is rather similar. The Ramon Crater, a tunnel, a hill, some ruins, a teacher and his two children, a family tragedy, a love triangle. Content dictates form, and it is as if Zvi’s dementia shapes the fragmented, perplexing way that the information inherent to the plot is revealed. The Tunnel is a puzzle that must be solved.

When The Retrospective was published in English in 2013, it seemed as if Yehoshua was preparing to exit the stage with a mediative and introspective novel whose stylistic virtues could not overcome the book’s soapy and overwrought narrative shortcomings. The Tunnel, though a novel which also has weaknesses in its plot, is on the other hand a fine valedictory note worthy of one of Israel’s finest writers.