Jonathan Spyer is a fellow at the Middle East Forum and a freelance security analyst and correspondent for IHS Jane’s. In February, Jonathan spoke to a Fathom-RUSI audience about what he believes we are witnessing in the Middle East today: the closing stages of revolutions and counter-revolutions and the emerging war over the ruins of the states, fought out between various state and non-state entities. Spyer explains how this process is being shaped by competition between various global and regional players, which is leading to the consolidation of non-state actors performing many functions of the state. Spyer also spoke about the contents and story behind his new book Days of the Fall: A Reporter’s Journey in the Syria and Iraq Wars (Routledge, 2017).

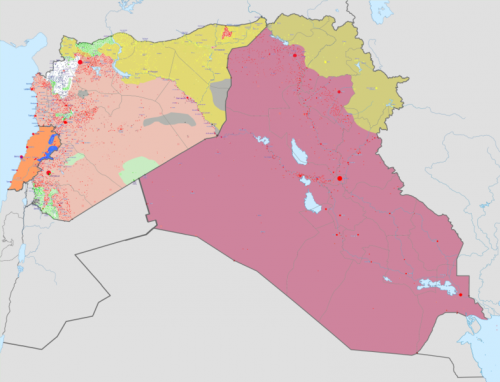

This map shows the current divisions in Iraq and Syria and is fairly accurate up to the present.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Transformational unrest in the Arab world

We are seven years into a process of very profound convulsion from below in the Arabic-speaking world: this series of revolutions, counter-revolutions and civil wars was initially misnamed the Arab Spring – nobody calls it that anymore. I contend that we may be in the closing stages of this particular episode of transformational grassroots unrest. The space we are interested in – between the Iraq-Iran border and the Mediterranean Sea – has witnessed a series of uprisings and a civil war. This process has collided with two separate dynamics, namely the 2003 US invasion of Iraq and its fallout, and the ongoing Iranian project of expansion into neighbouring states by the building of proxies. The collision of these three processes has led to a situation in which there is today no single functioning state that performs 100 per cent of the services we would expect of modern states, in the area in question.

Instead, there is a complex patchwork of areas of control primarily carved out by political/military organisation based on ethnic, sectarian or to some degree tribal affiliation, and an ongoing war over the ruins of the states, fought out between those various entities, some of which (at least notionally) describe themselves as the official government, but each of which has a lot more in common with each other than with a functioning state entity.

On top of this lies an additional patchwork which consists of competition between various global and regional players. With the single exception of the now declining Islamic State (IS – marked in grey in the map above) all the other players are supported or sponsored by regional and global powers. It’s a complex double patchwork.

Lebanon

In a certain aspect Lebanon is the easiest state to talk about because territorially speaking it is still intact, but I would argue that it is difficult to speak of Lebanon as a functioning state because the state structures have been effectively swallowed up by the powerful non-state political and military actor, Hezbollah. Since 2006 and 2008, it has been clear that Hezbollah was able to conduct its own foreign policy while ignoring the wishes of the sovereign government. And since 2016, the organisation has begun to absorb official state institutions. Hezbollah and its allies determined the appointment of Michel Aoun to the presidency of the country in late 2016. Today, Aoun talks about the vital role played by the ‘resistance’ (Hezbollah’s preferred term for itself). Seventeen out of 30 cabinet portfolios are controlled by the Hezbollah-associated electoral list.

Syria

Syria remains divided physically between a variety of forces, despite the recent advances of the regime. The regime and its allies control the main cities of the country and the coastal area, amounting to around 55-60 per cent of the territory, along with the majority of the population. The Sunni Arab rebels retain control of the al-Tanaf area in the east, Der’aa and Quneitra in the southwest, Eastern Ghouta in the centre, Rastan in the north and Idlib in the northwest, but they are in retreat. IS controls only a few rapidly eroding desert areas, and has been in decline for the past two years. But it is important to remember that IS first emerged as the al-Qaeda branch of Iraq and only later on morphed from an insurgency into a quasi-state. It is now in the process of morphing back. We should bear in mind the large extent of support IS still enjoys, particularly in western provinces of Iraq, and to some degree around Mosul. An IS military parade was conducted just west of Mosul in January this year, and up to 142 members of the Iraqi security forces have been killed by IS since October 2017. An area of control in the northeast, making up 27 per cent of Syria, is controlled by the Syrian Kurds, in alliance with the US. This area contains the greater part of Syria’s oil and gas resources, as well as some of its best agricultural land.

The Syrian regime is advancing in conquest most notably in the northwest, in the area of Idlib, the last province under near total rebel control. They have recently taken Abu Duhur air base, and are now 10 km from Saraqib, which they will undoubtedly capture in the weeks ahead.

All in all, there have been around half a million dead, six million internally displaced people, and up to six million external refugees. Syria is a country completely destroyed by the events of the last seven years with uncertainty of where it is heading.

Iraq

The government of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi officially controls the greater part of Iraqi territory. IS has lost its domain of open control. In the northeast the autonomous Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) has been in existence since the early 1990s. But again this picture needs to be expanded if we aren’t to benignly conclude, as some less sophisticated analysis has done, that the Iraqi state is reborn, the IS crisis is over and we’re back to fully-fledging government control. Why?

Firstly, the KRG conducted a non-binding referendum last year, in which 92 per cent voted to extricate themselves from the Iraqi state. They were prevented by force from moving ahead with this ambition. Secondly, the notion that the newly recovered government areas are fully governed by al-Abadi and his state security forces is optimistic in the extreme. IS, meanwhile, are still active on the ground in certain pockets.

The layer of global state sponsorship

A no less interesting or important second layer is that of state sponsorship. Lebanon today, fairly unambiguously, is under the control of Iranian-backed Hezbollah.

Regarding Syria, two schools of analysis contend: one view holds that the Syrian state is re-establishing itself across the country, and that hence Assad is on his way to restoring the status quo ante bellum of 2011. We need to complicate this view for several reasons. Firstly, whilst it is true that the area under the regime’s control is enlarging, if we look at the balance of power between the regime, and its backers Russia and Iran, we see that it is not the regime calling the most important military decisions in Syria today.

For example, on 20 January the Turks launched Operation Olive Branch in the Kurdish canton of Afrin in northwest Syria. The Syrian government issued a series of blood-curdling warnings against the Turkish government, threatening to down Turkish aircraft entering Syrian airspace. The warning did not deter the Turks from launching the operation. No attacks on the planes took place. It’s very clear that the Syrian regime does not decide which planes do or do not get blasted out of the sky. It is Vladimir Putin’s Russia which decides – due to the presence of two S-400 anti-missile systems in Lakatia province, and perhaps more profoundly because Assad owes his survival to Moscow. The so-called ‘returning regime’ of Syria is a regime militarily and diplomatically dependent on the support of the Russians, as well as of the Iranians with their tens of thousands of Shi’ite militia men on the ground.

In the government-controlled areas of Iraq the state is returning. IS has lost its domains. The Kurds are being prevented by force from leaving. But what is the nature of the state? The Iraqi government today is deeply penetrated by elements working under the direct control of Iran. For example, Iraqi Interior Minister, Qasim al-Araji, hails from the Badr organisation, a political-military organisation linked directly to Iran. So, the body which controls the federal police force is controlled indirectly by Badr leader Hadi al-Ameri, who in turn is controlled by Qassem Suleimani, commander of the Quds force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), who in turn answers directly to Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. This is the returning Iraqi state? Iraq is holding elections this May and contrary to the wishes of the US and Prime Minister al-Abadi, the PMUs are standing as a united list, called FATAH (conquest), and will likely hold key institutions following the polls. In their military guise, meanwhile, the PMUs are now protected in law as a permanently mobilised force. Their key components, however – Badr, Kata’ib Hezbollah, Hezbollah al-Nujaba, Asaib Ahl al-Haq – do not take orders from the government in Baghdad, but are rather directed from Teheran.

What do Lebanon, Syria and Iraq have in common? They are all beneficiaries of the most sophisticated programme of outreach being conducted by Iran. Unlike all the other major players in the region, Iran see this area as a single space and is operating a consistent policy across borders, whereby if President Assad gets into trouble you can bring in Iraq Shi’ite militias or Lebanese-based Hezbollah.

This differs from the US and Turkey, who don’t have a clear policy across state lines. I see American policy as confused – it remains committed to the notion of an independent Lebanese state outside of Hezbollah control. But it continues to financially and diplomatically support Lebanese state institutions at a time when these are under the direct control of a government dominated by Hezbollah and its allies. It is officially committed to the toppling of Assad in Syria but no longer supports forces committed to carrying this out. It appears to be entrenching its alliance with Syrian Kurds as Assistant Secretary of State (Acting) for Near Eastern Affairs David Satterfield, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Defence Jim Mattis have confirmed in recent weeks; but at the same time it is committed to its alliance with Turkey (as part of NATO), much to the disappointment of its Syrian Kurdish allies.

Regarding the Russians, a few points. Firstly, the Russian intervention into Syria in 2015, which undoubtedly did turn the tide of the civil war, was not a strategic masterstroke, it was an exercise in putting out fires. Let’s not forget the Syrian Arab rebellion was tantalising close to victory in the summer of 2015 – for the first time it had a single, powerful rebel force in northern Syria called Jaysh al-Fatah, which was heading westward toward Latakia, and had it broken into that province it would have been game over the regime. This is what the Russians came in to prevent. Secondly, in Sochi last week we saw that when normal rules of diplomacy apply, it is not that easy to turn a military achievement into a political achievement. Yes the Russians have defended the existence of the Syrian regime, but they failed to get the rebel opposition, armed or unarmed, or the Kurds to turn up to Sochi, and couldn’t convince the Europeans or US to go anywhere near it. Given that Syria requires over US $300bn in reconstruction, that’s an important factor too. The Russians have managed to preserve their ally, but they have not been able to dominate the space of Syria to such an extent as to dictate the outcome of the civil war. This was demonstrated very clearly at Sochi.

Days of the Fall

Days of the Fall is about all the above and more. It is an attempt to trace how the current reality came into being and to observe the various chapters of the civil wars in Syria and Iraq from the vantage point of witnesses and voices from below, as well as some of the key players. I spent a great deal of time reporting from Iraq and Syria and managed to speak to voices from all the various sides noted here.

The book begins at the birth of the armed rebellion in Idlib province in the winter of 2011/12 where I spoke to some of the recently defected soldiers and officers from Assad’s armed forces. It was the moment before the Islamists and Jihadists had come to the northern Syrian countryside and there was a genuine possibility of a local, non-Jihadi rebellion force emerging.

I follow that force as it bursts into Aleppo in 2012, Syria second largest city and a strategic gain for the rebels, which resulted in heavy fighting as the regime strove to drive the rebels from the city. We then travel eastward to witness the birth of Kurdish quasi-sovereignty, the first embryonic developments that have led, perhaps surprisingly, to a very stable authority in northeast Syria. During its first iterations this was a very ramshackle and improvised affair – the YPG didn’t even have uniforms in those first days – but there was a great deal of hope, optimism and determination.

The book then looks at the emergence of IS, out of the Iraqi Sunni insurgency, and its dramatic turn eastward as it crashed through the Iraqi security defences and Kurdish defences and menaced Irbil and Baghdad in the summer of 2014. I spoke to people in Iraq and in Syria and travelled very closely to Sinjar Mountain at the time when nearly 20,000 Yazidis were besieged by IS. I take the reader into the Newroz refugee camp, hastily assembled by the Syrian Kurds to rescue the Yazidis and save their lives.

I also look at the emergence of the Shi’ite militias in 2014/5 before turning back to focus on the second phase of the dying rebellion in late 2016 and the emergence, I think insufficiently reported, of the semi-permanent Syrian presence in southern Turkey – people starting to marry, to learn Turkish and finding work – and the sense that they may not be going home and that the survival and victory of the regime looking increasingly solid.

I end the book with a trip into Assad’s Syria, Damascus, Homs and Aleppo. In the conclusion I look at the ruins of the bombed out cities of Homs and eastern Aleppo, where there is very little remaining of infrastructure, water provisions, electricity and of course population. It is a stark witness to the way that brutal 20th century methods of warfare can prove still very effective in a military context. The book questions the notion of a return to strong states in Iraq and Syria, instead observing the emergence of semi-permanent frameworks and entities across both countries, as discussed earlier.

Conclusion: The demise of strong states and their structures

I’ll conclude with some observations of where things in Syria and Iraq may be heading. The penetration of the Syrian regime by Russian and Iranian power and the extent to which these states are taking the key military decisions on the ground cannot be overstated. At the same time, what remains of the Syrian Arab rebellion today is not a revolution, nor even an insurgency, but a series of military contractors, armed men, who effectively work for the interests of foreign governments. For example, the ground forces that the Turks have taken into Afrin are not Turkish infantry, but organisations such as Nur al Din al-Zinki, Faylayq ash-Sham, and so on. The remnants of the rebellion in northern Syria. And in southwest Syria, the rebel groups such as the Southern Front, are working for the Jordanians or such groups as Fursan al-Jolan for Israel in various localised contexts.

Similarly, the marriage of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)-affiliated the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the US, whereby the US Ministry of Defence has found a group of ground partners who are not Sunni jihadist and are good at ground combat, is perhaps the most fascinating of all, and it is working, and looks set to continue.

What we’ve witnessed in Syria over the last seven years is a demise of strong states and their structures and we’re still in the process of witnessing the birth of what may be to come. My book and also a great deal of my attention is on the human costs of that process, and not solely the political dimension of it.

Q&A

Question 1: The buzz word these days is DDR – demobilisation, disarmament and rehabilitation – which is particularly key for non-state actors. In the book you speak to a member of an Iraqi Shi’ite militia who says, ‘The Iranians have an army and the IRGC, so why don’t we have it here?’ Is this model the type that Syria and Lebanon will aspire to, at least under an Iranian guidance? Or is it possible to centralise anything into what we might recognise as a more unitary state structure?

Jonathan Spyer: The officer I was speaking to was from the Badr organisation, not from one of the smaller Iranian-backed groups, but from the largest and most integrated of the pro-Iranian Iraqi Shi’ite militias. He stated very clearly that the PMUs should come to replicate the IRCG, which is already a long way down the road toward fruition. Those who genuinely believed that the PMUs would be disbanded after the defeat of IS have already had their expectations frustrated. The PMUs were written into law last November, meaning they will undoubtedly be a present actor in Iraq.

This leaves the question: can they be integrated into the official security forces? Here one has to look at the nimble way the Iranians mix political and military categories that no other regional country is able to do. Think of Badr, Ahl al-Haq, Kata’ib Hezbollah and the other factions in Iraq that are coming together for elections in May. What is happening is that leaders of the PMUs are also, when not carrying arms, coming to constitute a very powerful political contingent within the country, which is going to hold more power after May. So the ambiguous situation in which the Shi’ite militias continue to answer to commanders abroad, carry arms and operate in Iraq – such as in Kirkuk last year – is going to continue happening and the West needs to be aware of that because otherwise it will be very easy to create policies which will end up benefiting Iranian interests inadvertently, through maintaining the illusion that neutral state institutions still exist.

What is the Achilles heel of Iran in the region right now? What can other actors in Syria do together with the US to slow down, stop and rollback Iran?

The Iranian and Russian contributions to the survival of the Syrian regime has been profound. The Russian intervention in Syria is mainly air power, small number of Special Forces and some military contractors. This isn’t because Assad didn’t have problems when it came to ground forces but because another friend had already addressed it: Iran.

What the Iranians are doing in Syria is two parallel things: mobilising foreign proxy forces and bringing them into Syria (we know of the role of Hezbollah, Iraqi Shi’a militias, the Afghani and Pakistani Fatemiyoun and Zeynabiyun divisions and so on); and creating a parallel armed force alongside the existing Syrian army, called the National Defence Force (NDF), which has an auxiliary force of around 60,000 and has been absolutely crucial for the regime’s survival. I was in Damascus last year and if you go to the city’s many checkpoints, they are not run by the army but by the NDF, enabling the army to go out and engage rebels in the countryside.

This leaves the Iranians with a very strong had to play. Unlike the Russians, the Iranians actually control a military force of tens of thousands of fighters on the ground, who take orders from Iran, not Assad or Putin. The Iranian goal – which is not to create a strong state but rather patchworks of Iranian control within the state – has been achieved in Lebanon, and in Iraq, and they are now on their way to achieving it in Syria. The failure of the Western-backed forces to reach the Albu-Kamal crossing (between Iraq and Syria) at the end of last year enabled Iran to have a contiguous line of Iranian control from Iran through to Damascus. Iran hasn’t achieved pushing that line to the Mediterranean Sea, yet but they are not far from achieving it.

The West needs to understand what the Iranians are doing, how they are doing it, and then think about how it could be replicated against them. For example, Western states can also effectively mobilise political and military allies – like the US did in 2014 when it made a decision to destroy the IS and found an ally in the Kurds and have largely achieved that aim. There are other forces on the ground available for mobilisation, not only the Kurdish forces but also what is left of the non-Jihadi rebels in southwest Syria (the Southern Front has around 30,000 fighters, and when I was in Amman Southern Front officials told me they are still hungry for Western support), and other rebels forces in Raqqa and Hasakeh and Quneitra, which for opportunistic reasons would receive external support if the West still wishes to get into the game. I believe this is the only method that can produce results. Having the illusion that centralised state institutions is the way to combat Iranian advancement will end in failure and in embarrassment.

Question 2: What is the perception of the West among the rebels? And given this great game strategy, who is that perception going to help embolden to the two Western allies?

JS: The perception of the West is unambiguous, and is shared both by friends and enemies. The West is considered weak, largely absent, and almost entirely unreliable, and it is a perception unfortunately not entirely without foundation.

Everybody looks at the stark contrast between the verbal support given to the rebellion against Assad, particularly in the first couple of years of the civil war and President Barak Obama’s 2011 call for the Syrian president to step down, and the pitifully dire subsequent assistance forwarded to the rebel as the civil war materialised. We all remember the 2013 red-line on the use of chemical weapons, but it’s not only about criticising the Obama administration; look at the Trump administration, it sent Tomahawk missiles in response to the Khan Sheikhoun attack last April, but this appears not to have marked an actual change in policy. It was the Trump administration, not Obama, which finally cut off financial contributions in their entirety to the remnants of the Syrian Arab rebels in southern Syria, whilst remaining committed to the alliance with the Kurds east of the Euphrates. So no one is quite sure where all this is heading in terms of clear policy. There is a general sense the West doesn’t want to get involved in the Middle East as heavily as before, and therefore it is not a reliable ally.

This leaves the Russians and the Iranians energised and more confident. Yet they don’t have everything their own way either; there is plenty to work on in terms of the limitations of their agenda. The in-built in vulnerability of the Iranians is that in spite of their gain in confidence from Western disengagement, they are only able to build lasting strategic alliances with other Shi’ite or minorities forces (rather than with Sunni Arabs). However, there aren’t enough Shi’ite communities to enable them to control the whole region.

For the Russians, they are not really willing, or perhaps able, to put in sufficient money and people to dominate the space in Syria. Instead they’ve been pursuing ‘diplomacy of shadows’ in which you have a conference and declare victory but in reality you lack the financial capacity to start reconstruction. So although the West is perceived as absent, that doesn’t mean it has been replaced by a clearly powerful, unstoppable force that moves freely into the space.

Question 3: Would you say that borders are increasingly seen as being irrelevant, or is there a desire to redraw them or to even maintain them as they are?

JS: There is a very clear and notable desire from the international community to maintain existing borders and to not allow the emergence of new, legitimised entities. Having said that, there is also a very noticeable fragmentation on the ground which includes the capture of parts of borders by forces who don’t possess international legitimacy to control them. An obvious example is that if you travel from north-western Iraq into north-eastern Syria, you are required to have your passport stamped by two entities – the Kurdish Peshmerga in Iraq and the Kurdish YPG in Syria – which legally speaking have no right to check you across the border line.

Despite the rhetoric, the international community are reluctant to counteract the emergence of new entities as well as the loss of border control to such entities. The Assad regime lost the majority of its border with Turkey to the Kurds, Arab rebels and the Turks as long ago as 2012, and it’s not close to reconquering it any time soon. Some border crossings, like Nassib between Jordan and Syria, are key trading routes and still remain in the hands of the declining Arab rebellion. The important border crossings for trading in the north are all controlled by non-government forces and my sense is that this situation is more durable than it seemed previously. There is a certain amount of tacit Western acceptance to this as well. In October 2017, the British and Americans didn’t want the Iraqi armed forces to venture further north and retake the Fish Khabur border crossing with Syria, but preferred the Kurds to remain there.

Question 4: What do you think is Turkey’s plan is for the Afrin canton?

JS: There is clearly a determination to not allow the Kurds to control the entirety of the Syrian-Turkish border, and that was partly achieved last year during Operation Euphrates Shield. There is now a desire to further minimise the Kurdish gains and to register the extreme Turkish displeasure with the US at the apparent longevity of its relationship with the Syrian franchise of the PKK, the YPG (according to the Turkish reasoning). My sense is that the Turkish-backed forces will not turn east and head to Manbij. I think this is more a game of brinkmanship; Erdogan has elections coming up next year, and there have been minimal Turkish casualties. It’s hard for me to believe that for someone as canny as Erdogan, he would get involved in a fight with US forces in Manbij.

In fact, what’s interesting to note, is that invading Afrin is like picking on the smallest kid in the playground if you want to show you’re a tough guy. Why? Erdogan would really love to push the Kurds east of the Euphrates but the US are present and therefore he can’t do it. He’d also love to put up a tough fight for the Syrian rebels in Idlib province against the Syrian regime, but that is not possible for him. So since he wants to do something to show he’s assertive and powerful but can’t push the Kurds back, or fight for the rebels in Idlib, he has attacked the Afrin canton, which is protected only by Turkey’s arch enemy, the PKK. Yet, also there, the Turkish advance since January has been extremely slow. They’ve conquered about 4 per cent of the land and a couple of important hills close to Azaz, but they haven’t yet pushed decisively further in. My sense is this is not only because they cannot, but because they don’t really want to. They don’t want to enter Afrin city because it will likely cause a ferocious PKK uprising in the streets – Afrin is a historic centre of PKK support. It is very possible that in the near future the Turks will say that they have prevented the immediate danger of the Kurds using the canton as a launchpad by carving out a buffer zone and subsequently declare victory and remain in place.

Extremely cogent.

Perhaps I am alone in this, but the functional sponsorship of ISIS by Turkey seems to be quite apparent. Was it not the transfer of US weapons to ISIS through Turkey and the melange of jihadist rebels that caused the Obama administration to cease support of the FSA? It was certainly apparent that the border was porous to ISIS recruits while it was closed to Kurds. MIT was at one time embedded with ISIS forces. The blockade of Kurdish-controlled areas was complete at the same time the supply lines were wide open to Raqqa when ISIS controlled that city. (writer realizes he is not like to get a response, but just puts the issue there.

Brilliant analysis, as usual, but why does the map have no key? Is that some post-Imperial British map phobia thing, Jon Spyer? 😉