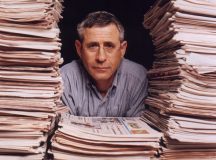

Asher Susser explains the resurgence of tradition throughout the region and its political consequences for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He was speaking to a Fathom Forum in London on 10 February.

One of the main failures in Western analyses of the Arab Spring was the underestimation of religion as a factor in Middle Eastern politics. When it began, everybody started talking about the secular liberals. The problem is, the secular liberals are virtually non-existent in Arab society – the people who really matter are the Muslim Brotherhood.

If you want to talk about real political organisation, it is invariably of an Islamist character, these days. I wrote a monograph about this five years ago. I examined the rise of Hamas to power in Palestine, arguing that this was not an exceptional development – it was the rule.

When you have free elections, the Islamists either do extremely well or they win. When Jordan had relatively free elections in 1989, the Islamists of various brands got around 40 per cent of the seats in Parliament. The Jordanians have since then cheated in the elections systematically to keep the Islamists out. They changed the election law, fraud, violence – whatever you like – anything but allowing the Islamists to cash in on a free election.

Why is tradition so resilient? I would cite four factors.

Top-Down Secularisation

First, there is a top-down character of the secularising reforms introduced in the Middle East over the last 200 years or so. The point of departure of what we call the ‘modern’ era in the Middle East begins with the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt in 1798 – that was the crushing introduction of European power and European ideas which induced a period of reform in the Middle East.

However, these secularising and westernising reforms were ‘top down’. They did not come from bottom up. As a result, very often, the people didn’t want them. And there was always a traditionalist push-back against these secularising reforms.

Take a country like Turkey where the most impressive reforms were introduced during the Tanzimat. These Ottoman reforms, beginning in 1839, ended in 1876 with the introduction of the Ottoman constitution. So you could say that Turkey had gone the furthest in this process of secularising westernisation. But then look at Erdogan today – he is able to cash in on the Islamist sentiment of the bulk of Turkish people.

You see, the reforms that were introduced in a very far reaching fashion under Kemal Ataturk were introduced by force. Ataturk was a dictator – the Latinising of the alphabet, for example, was imposed on the population. That’s why, with the democratisation of Turkey after the Second World War, you have the gradual resurfacing of the Islamic tendency.

Across the Middle East, there may have been secular reforms, but they didn’t produce secular societies. The societies remain in their heart of hearts basically attached to religion.

Societies of Groups not Individuals

There is a great book written by a British historian of the Middle East, Malcolm Yapp. The point he makes is that Middle Eastern societies are not societies of individuals – they are societies of groups. And this is the second factor explaining the resilience of tradition.

Western societies see themselves as societies of individuals. The rights of the individual are at the core of political debate, guaranteed by the state. People organise politically as individuals; they join the Republican Party, or the Labour Party, whatever it is – as individuals.

The Middle East, Yapp said, is not a society of individuals – it never was – it’s a society of groups.

You belong to a group – that is, your family, your extended family, your tribe, and perhaps above all else, your religious denomination. So, you are first and foremost a Muslim, or a Jew, or a Christian – and some kind of Christian at that, either Maronite, or Greek Orthodox, or Greek Catholic, and these differences matter. If you’re Muslim it makes a huge difference if you are Sunni or Shiite or a member of the heterodox non-Muslims like the Alawites or the Druze, who are not really Muslims at all.

The Americans invaded Iraq with the belief that it was a society of individuals and so would coalesce into democratic political parties which would vie for power. But what happened? The groups went to war with each other! The civil war, Sunni vs Shiite, was only to be expected – it couldn’t have been otherwise. And I’m not saying that societies of groups are better than societies of groups of individuals – just different.

Why do we keep getting this wrong? Well, in the West, one unfortunate by-product of Edward Said’s influence is the unwillingness to recognise the Otherness of the Other. In multicultural societies in the West – and I have nothing against multiculturalism, I’m all in favour of it – you have societies which see themselves as multicultural. But look, if you define yourself as multicultural, you are obviously recognising that other cultures are ‘Other’, therefore multi! But when the multiculturalist from the US and other Western states looks at the Middle East, he or she explains Middle Easterners not as Other, but as… us! That’s why we got this whole story about Facebook and Twitter during the Arab Spring. It was a way of saying, ‘They’re just like we are!’

Westerners saw Facebook and Twitter but didn’t see the Muslim Brotherhood. The story in the West was ‘This is Facebook and Twitter; this is the 21st century; this is the secular liberal intelligentsia taking over Egypt.’ And then the commentators were shocked when the Muslim Brotherhood walked all over everybody. But they were obviously going to walk all over everybody! The only people who are going to prevent the Muslim Brotherhood from walking all over everybody is the military – not the secular liberals. The secular liberals, to kick the Muslim Brotherhood out of power in Egypt, had to use the military – nobody else could do it.

Religion and State

Third point: there never really has been a separation between religion and state in the Middle East. No matter how far the reforms went in the Ottoman Empire or Egypt, there was always a place for Islamic religion and law in the state. In the last 20 or 30 years, this space has increased. Even under Mubarak, Islamist lawyers would file suits against intellectuals for blasphemy in the regular secular court system – and they would win. The reintroduction of Sharia into the secular court system was allowed by Mubarak. Why? Well, there was a kind of deal – the Islamists were allowed to take over a certain segment of the public space provided that they didn’t mess with the government. (Eventually, they messed with the government, but that wasn’t the original idea.)

Territorialisation of identity

The fourth point is the impact in the Middle East of a genuinely westernising influence, which I call the territorialisation of identity. The Ottoman Empire may not have been a liberal country, but it was a very tolerant country. Minorities and majorities lived side by side in peace throughout the empire. But the advent of the Western idea of nationalism brought the related idea of linking society, community, and territory, and this led to horrific bloodshed throughout the region.

Once it became important to territorialise your religious identity, we saw military confrontations between communities. This is what happened in Yugoslavia. This is what happened in Cyprus. This is what is happening now in Iraq. This is what broke Lebanon up. This is what is now breaking up Syria.

Neo-traditionalism

The chaos in the contemporary Middle East is the cataclysmic expression of the failure of Western style modernisation. These are failed states which cannot provide for their people, and the people are rebelling against hopelessness. Egypt is the perfect example of that.

The inability of these societies to provide a decent life for their populations, and the widespread disillusionment with Western-style modernity and reforms, has produced the resurgence of what I call neo-traditionalism: political Islam, sectarian politics, tribal politics. In Egypt and Tunisia we see the Islamists versus the Secularists, in Iraq and Syria we see sectarian civil war. In Yemen and Libya there is tribal disintegration. The entire region is being destabilised because of this resurgence of neo-traditionalism.

How does this infringe upon the Arab-Israeli issue? As the residue of secular nationalism retreats into the background, religious forces in the conflict are becoming more salient. Hamas and Hezbollah are definitely far more motivated, and more central, to the armed conflict with Israel than Fatah and the remnants of the PLO.

Israel is also changing. Israel post-67 is not Israel pre-67. Israel post-67 is has a much more religious kind of Zionism as a result of the Six-Day War and the occupation. The Messianic component of the Zionist endeavour is increasing. Classical Zionism was actually a way to push religion out of Jewishness. It was an effort to create an alternative, secular Jewishness, hence the opposition of the ultra-Orthodox to Zionism. There was always this rather marginal religious Zionism, but after 1967 it became far less marginal and is an ever increasing segment of Israeli politics.

For religious Zionists, the State of Israel is not the secular territorial expression of Jewish self-determination; it becomes the vehicle for religious redemption. Atchalta de’Geulah, as they would say – ‘the beginning of redemption’. This is the opposite of what the secular Zionists of the earlier phase intended.

On the Jewish side and on the Muslim side, the conflict is becoming more religiously motivated. Israel demands the unification of Jerusalem ‘by hook or by crook’ under Israeli sovereignty. There is, I would say, a not very well treated Arab minority within the city. We see Jewish fanatics settling in Muslim residential areas as part of the takeover of even Muslim residential areas. And we see Jerusalem turning into the flash point of what is becoming an increasingly religious confrontation.

Abu Mazen has taken the confrontation to the UN and the ICC, while Hamas has taken it to the battlefield. The armed element of the conflict is becoming driven by religious motivations while the secularists are taking the confrontation somewhere else.

The increasingly religious nature of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the increasing focus on Jerusalem, are both deeply rooted in what I am calling the resurgence of neo-traditionalism.

I have been saying much the same thing for decades, now. No one would listen. Nor would they learn from the mistakes they repeatedly make for not having learned.