Perry Anderson and the House of Anti-Imperialism

Editorial introduction to the Symposium: Perry Anderson’s long essay, ‘The House of Zion’, was published in the November-December 2015 issue of New Left Review, the ‘flagship journal of the Western Left’. Fathom invited Mitchell Cohen, Shany Mor, Cary Nelson, John Strawson, Michael Walzer and Einat Wilf to respond to Anderson’s essay.

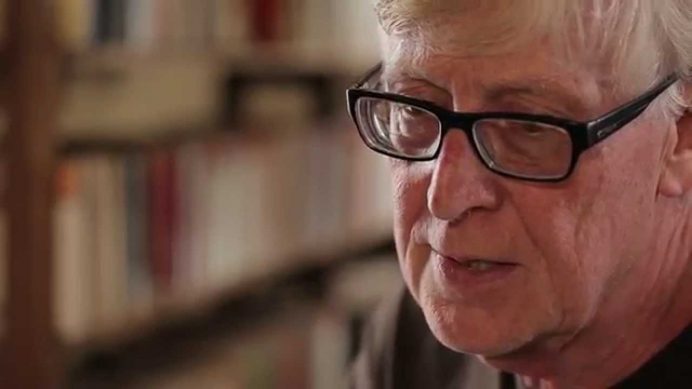

Available online, and given the status of an NLR ‘Editorial’, it was the Marxist equivalent of a Papal edict. Anderson was the journal’s long-time editor, and is perhaps the most gifted intellectual historian of his time, author of Lineages of the Absolutist State, Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism, Considerations on Western Marxism, English Questions, The Origins of Postmodernity, and more. In this outing, Anderson serves as episcopus servus servorum Dei, or, the servant of the servants of God (in this case a secular God). Over 14,000 words, he excommunicates the two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and anoints an alternative: ‘the demand for one state is now the best Palestinian option available.’

Anderson’s essay is a summa of the thinking of the Left that has lost its way on the question of Israel. For one thing, his proclamation proceeds untouched by the categories with which classical Marxism has traditionally approached unresolved national questions: ‘internationalism’, ‘chauvinism’, ‘peace between nations’, ‘people’, ‘class’, ‘consistent democracy’, ‘the right to national self-determination’, ‘minority rights’, and ‘federalism’. Instead he prefers the decidedly non-Marxist categories of ‘the Arab states’, ‘their traditional enemy’, the homeland’, ‘the West’, ‘Arab turbulence’, ‘the Zionists’, ‘the Resistance’ and ‘the New World Order’.

Anderson’s dream that the ‘strategic emplacements’ of the Arab states will end the existence of Israel is a far cry from the Marxism of Lenin, who believed national self-determination and consistent democracy was the way to ‘clear the decks for the class struggle’; from the sophisticated discussions of the national question, the rights of peoples, and the mechanics of federalism of the first four congresses of the Communist Third International; and from Trotsky’s late support of the Jewish people’s right to survival as a nation and to live as a ‘compact mass’. In place of all that, conspiracism is passed off as sophisticated geopolitics, class politics is bracketed ‘for the duration’, and fascistic political forces are embraced as ‘the resistance’.

*

Mitchell Cohen, social democrat and long-time co-editor of Dissent magazine, reads Perry Anderson’s New Left Review essays on Israel, including ‘The House of Zion’, symptomatically, as examples of long-standing intellectual maladies on the far-left – Manicheanism and teleology. Analytically, Anderson has reduced the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to no more than a facet of a battle between the House of Imperialism and the House of Anti-Imperialism. Politically, he wants war. A credible left, argues Cohen, can do better than that.

I.

As I write highly cultured ‘theoreticians’ are bombarding people for thinking like me across the intellectual and university worlds.

Perry Anderson’s ‘House of Zion’ in the recent New Left Review (hereafter: NLR) exemplifies the campaign. Probe its animating animosity with discernment, and in light of some of his other writings, and you may reach a conclusion contrary to that intended by him and those of like-mind (like BDS). Obsessive anti-Zionism signals something wrong within the left.

Zionism arose partly from mistrust – of Western Christian societies, of Western liberalism, and of the reaction, including within parts of the left, to Jew-hatred: yes, there’s this long history of nasty bigotry but all will be well if you just hang on and fit yourself into our vision of that past and the future.

And in the meantime? Some other men and women, Jews and non-Jews, saw in this kind of response a misguided moralism – it masqueraded sometimes as ‘science’ – harboring a facile universalism. Anderson’s essays suggest why mistrust was, and alas still is, warranted.[1]

Consider what was missing or misrepresented when Anderson tried to account in his essay ‘Scurrying towards Bethlehem’ (NLR, July-August 2001) for the origins of Zionism: the pogroms of 1881, the ensuing tremor-filled decades and then in 1903 and after a new wave of anti-Jewish violence in the Tsarist empire. He mentioned ‘Christian anti-Semitism’ but his outrage seems token if compared to his tone when addressing imperialism. He provides little sense of the ravage and trauma of these events. For many Jews, they shattered faith in a Russian future, which is why some of them took to the idea of reinventing their victimised people as a nation. Their watchword was ‘Auto-emancipation,’ that is, self-determination – an end to dependence (including on leaders of their own communities). The socialists among them said: yes, we do hope that in the long run we shall all be universal, but in the short term we will be dead as the target of something quite particular, Jew-hatred.

Imperialism had nothing to do with it. Anderson seems driven to make it the issue, portraying Zionism (and later the Jewish state) as nothing but its beachhead or manipulator, or both. Excised also from his narrative are mass anti-Semitic movements, often speaking an anti-Capitalist language in late 19th century Germany and France.

He points, of course, to Theodor Herzl’s attempts to secure backing for a Jewish national home from a Great Power. This, for Anderson, reveals Original Sin. Yet what he ends up showing is his own arresting inability to grasp how members of a demonised minority struggled to respond to what they judged (pretty rightly) to be an increasingly precarious world. The author of ‘House of Zion’ does not grasp why hounded people would say: we need a home.

So what if Herzl sought out Great Powers? During the American War of Independence, Britain offered liberty to slaves in the south if they fled their masters and joined, well, let’s call it the Counter-Revolution. Would Anderson have told those victims of unspeakable brutality: ‘Don’t do it! You’ll be imperialist pawns! One day there will be universal liberation! Ignore your shackles and join the struggle!’

II.

The problem lies in an approach to history and politics as much as in details. Call it ‘The Perry Anderson Version.’

Marx once wrote that a key to the anatomy of the ape is found in human anatomy. This is only partially so; multiple keys are always needed to understand historical developments. Otherwise we look back with one eye, forward with the other, and believe there is a seamless continuum of perspective. A wise essay, Herbert Butterfield’s The Whig Interpretation of History, warned long ago of a ‘trick of organisation’ that produces distorting teleology. When this happens the past is read uncritically as a function of understanding the present and both get distorted. An ‘unexamined habit of mind’ effectively edits out all kinds of essential mediating factors and contingencies, providing instead a ‘short cut’ to ‘absolute judgments that seem astonishingly self-evident.’[2]

Among the unfortunate consequences of turning ‘our present’– but also, I’d add, hardened world-views – ‘into an absolute to which all other generations are merely relative’ is that we then lose sight of where our own ‘ideas and prejudices stand.’ Just so in Anderson’s arguments, except that they are colonised by a negative teleology. Virtually all bad things are to him offshoots of imperialism, an absolute he deploys so broadly that it becomes meaningless all while it informs strenuously pronounced verdicts. Meanwhile, there is collateral damage: understanding of other powerful forms of oppression.

Butterfield noted, with appropriate tang, that ‘for the compilation of trenchant history there is nothing like being content with half the truth.’[3] Or less. Consider ‘Renewals,’ Anderson’s editorial for the ‘new series’ of NLR (January-February 2000). From an ‘historical perspective,’ he wrote, the world had changed in the four decades since this journal’s embrace of Third Worldism and non-Stalinist Marxism (usually neo-Leninist-cum-neo-Trotskyist variations).

And a decade after 1989 everything appeared to be over. Left-wing ideas seemed exhausted all while global capitalism in its neoliberal form was unfettered. There were, wrote Anderson, ‘no longer any significant oppositions – that is, rival outlooks – within the thoughtworld of the West.’

It seems that the point is: nothing turned out as we theorised but that doesn’t mean we got any basics wrong.

Absent: searching scrutiny of thought worlds and habits of mind of NLR to find out what they got wrong and what partial truths were taken for the whole. Time just to renew.

Missing: An intellectually fresh and convincing left, one that doesn’t simply apply old recipes to new realities – the kind of left that is imperative to address our world’s multiplying woes: social suffering, structured reproduction of economic inequalities, global poverty, a trembling climate, corrosion of democracy, very immediately, a massive refugee problem.

Yet look to where Perry Anderson points the left. As death tolls in Syria and Iraq veered towards 400,000 in winter 2015-16, the editor of New Left Review wrote 14,000 words excoriating… Zionism. Is something wrong here?

III.

‘House of Zion’ is not simply a protest against the grim state of Israeli-Palestinian relations. It fashions a shiny object for a post-Marxist left to chase instead of insisting that we rethink our world. That object comes of intellectual alchemy – melding lazy notions of ‘imperialism’ with tedious fixations on ‘the Question of Palestine.’ It is one thing to criticize permanent occupation of the territories taken by Israel in the 1967 war. It is another to reduce, as Anderson does, Zionism to just one of many eastern European nationalist movements of the 19th century, albeit the fortunate one that linked to the imperialists, while making Palestine into an issue of almost incomparable magnitude, the lodestar for anti-imperialists.

His ideal of ‘One State’ to dissolve the Israel-Palestinian dilemma means, of course, the end of Jewish statehood. It would, he writes, ‘transcend the original division of the country’ and address ‘the enormity of the plunder,’ even if this prospect has ‘its own hidden reefs.’

But those reefs are hardly hidden. Beneath shallow waters there is not ‘One State’ but a permanent ‘Civil War Solution.’

Oddly, ‘One State’ is just what rightwing Israeli zealots pursue. We seem, then, to have an overlapping consensus of contrary ideological hallucinations: teleological anti-imperialism from the Anderson left and pursuit of ‘the whole land of Israel’ from the Israeli far right. If you like what has been happening in Syria and Iraq in recent years, then that’s a vision for you. It may not be so for Israelis and Palestinians who stand to suffer for it.

Perhaps, before it commits to Anderson’s programme, the anti-Zionist left needs to ponder words by Isaac Deutscher, biographer of Trotsky and a mentor of Anderson. Anderson quoted them himself once, although in another context and without allowing for all their implications. Marxism, according to Deutscher, would ‘show a lack of moral courage’ if his generation – he means Marxists who committed themselves to Leninism and lived through the calamities of Stalin – simply drew a ‘formal line’ and declared ‘we are not responsible for Stalinism, that wasn’t what we aimed at.’ To an extent, Deutscher acknowledged, ‘we … participated in this glorification of violence as a self-defense mechanism.’[4] In today’s terms: you cannot just press a delete button at a later date. Advocates of ‘One State’ for others might do well to contemplate Deutscher’s insistence on facing-up-to-things.

IV.

Anderson’s loathing of Israel corresponds to a long history of unfortunate thinking in part of the left. What is the link? Consider that Anderson once classified George Orwell’s 1984 as ‘the centerpiece of the phobic literature of the Cold War.’[5] Orwell’s socialist warning about Stalinism was made out by Anderson’s formula to be little more than an agitation on behalf of one side in the contest between the West and the Soviet Union. It is in a similar spirit that Anderson reduces Israel’s birth to no more than a facet of a battle between the House of Imperialism and the House of Anti-Imperialism.

Anderson’s simplistic rendition of history brings him to an odd, sneaking appreciation for the Zionist right, both practically and intellectually. He credits the ‘anti-imperialist campaign’ of Menachem Begin’s underground, the Irgun, for convincing the Kremlin to support the 1947 UN plan to partition Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. (How that claim meshes with his insistence that Israel was created as a cop for the West is unclear.) Perhaps he is a bit too taken by Begin’s rhetoric – one might call it biblical anti-imperialism on behalf of integral nationalism – since Moscow’s support for partition rested in fact on its determination that a Jewish state was bad for British imperialism. Moreover, Zionism’s leadership and diplomacy were dominated then by a left-wing labor movement – its leading party, however, was unsympathetic to Bolshevism – and not by the Irgun. Israel won the ensuing war thanks to Soviet bloc weapons while the West upheld an arms embargo.

Anderson’s essay even converges with the historiography promoted by the ‘Revisionists,’ the Zionist right-wing founded by Vladimir Jabotinsky and led after his death by Begin. The Revisionists insisted that they, not the socialist-Zionists who wanted to mix universal principles with particularist needs, incarnated true Zionism. Not only is the editor New Left Review in accord, he even judges the ‘Revisionist tradition’ to be of ‘greater intellectual distinction’ than the Zionist left. How he reached this verdict is a bit mysterious since relatively little Revisionist literature exists in languages that he reads. (The same is so for the relevant Labor Zionist writings).

The tortured intellectual underpinnings of Anderson’s account come out, however, when he contends that the right-wingers were ‘more independent minded’ than the ‘pragmatic,’ compromising Labor Zionists. When it comes to the Revisionists, ‘names remain a clue to things,’ he writes. In their contemporary incarnation (the Likud), ‘the appetite comes with the eating, and what is mere nomenclature today is likely to acquire some reality tomorrow.’

What names? Anderson doesn’t really say but it is easy to surmise from his claims that the important one is ‘Revisionist’ itself. It has long been a label for treason summoned by the harder left for anyone who adjusts Marx’s theories towards reformism (or just, in my view, in light of reality) rather than revolution. For Jabotinsky, that same word, ‘Revisionist,’ was no epithet but indicated his identification with the initial quest of Herzlian Zionism for a charter from a Great Power. Zionism had gone astray, thought Jabotinsky, with Labor’s attempts to build communes in Palestine and with its strategy of moving step by step towards a democratic and Jewish state.

A certain confusion results. Whether ‘revisionist’ means social democratic compromise or the essence of Zionism, Anderson is, finally, against it. (Well, at least the Zionist right wasn’t reformist).

The truth of Zionism’s socialists for Anderson is revealed by the Revisionists.

So, the ‘One State’ solution speaks for itself; two states would be comparable to social democratic compromise.

V.

Anderson’s claim that the post-colonial Middle East and North Africa suffered from ‘a virtually uninterrupted sequence of imperial wars and interventions’ is also one dimensional. While not entirely false, he grants no explanatory power to indigenous conflicts and factors in explaining what happened. Those events, says Anderson, ‘began as early as the British expedition to reinstall a puppet regent in Iraq in 1941 and multiplied with the arrival of a Zionist state on the graveyard of the Palestinian Revolt, crushed by Britain in 1938-9. Henceforth an expanding colonial power’– Israel – ‘acting sometimes as a partner, sometimes as a proxy, but with increasing frequency as initiator or regional aggressions was linked to the emergence of the United States in place of France and Britain as the overlord of the Arab world.’

Unmentioned: much of British policy in the 1930s, which turned increasingly against Zionism. For examples: the Passfield White Paper of 1930 which came close to annulling the Balfour Declaration; the Peel Commission Proposal of 1937, while Hitler was getting busy, which offered Zionists a modest enclave on the Palestine coast and in Galilee and was rejected by Palestinian leaders as a compromise; the White Paper of 1939, fashioned by the government of a great Conservative peacenik, Neville Chamberlain, which virtually quashed British support for Zionism.

Also, notably unmentioned: that the British expedition in 1941 attacked by Anderson reversed a pro-Axis coup led by Rashid Ali al-Gayani under the banner of anti-imperialism with backing from Hajj Amin el-Husayni, the exiled Mufti of Jerusalem and leader of Palestinian nationalism. Both of them received support – the Mufti already during the Palestinian Revolt – from Berlin and Rome.

Both fled to Berlin after Britain intervened. The Mufti was tireless there in his enthusiastic support of the Third Reich.[6] Although it did not include inventing the idea of the Holocaust, as Benjamin Netanyahu fibbed to a Zionist Congress in 2015, what the Mufti did was damning enough.

How would Anderson have voted had he been a member of Parliament in 1941 and had the Conservative prime minister Winston Churchill asked for a vote of support for that expedition? Would he have declared ‘No Blood for Oil or Empire!’ and repeated the anti-imperialist speeches of Rashid Ali and the Mufti, while Rommel was in North Africa and Axis control of Mideast energy supplies was at stake?

Anderson goes on to tell us that a ‘spontaneous uprising’ of Palestinians came after the UN partition vote of 1947. While most Palestinians were surely dismayed at the resolution, this ascription of spontaneity to a society of clans and social hierarchy is no less of an historical distortion than crediting the Irgun with Moscow’s vote for partition. Before the ballot, the head of the Arab League, Abdul Rahman Azzam Pasha, told the press that a ‘yes’ vote would bring a ‘war of extermination’ against Jewish Palestine. In the coming combat, he warned, ‘the number of volunteers from outside Palestine will be larger than Palestine’s Arab population.’ These troops would have three essential features: ‘First – faith; as each fighter deems his death on behalf of Palestine as the shortest road to Paradise; second [the coming campaign] will be an opportunity for vast plunder. Third, it will be impossible to contain the zealous volunteers arriving from all corners of the earth.’[7]

Add the Mufti’s record in Berlin, which included many blood curdling radio rants, to Azzam Pasha’s words and you might reach the conclusion that there is something about how Jewish Palestine (and not just Jews there) understood the world in 1947-8 that Perry Anderson just doesn’t get. Or doesn’t want to get.

Consider how far he goes to show that it was an alliance with imperialism rather than a reaction to anti-Semitism that is the key to Zionism. There was, he proposes, no real relation between the Holocaust (the Shoah) and Israel’s founding. The link was a Zionist invention for self-justification. After all, Jewish statehood came with what Anderson calls ‘ethnic cleansing’ [of the Palestinian Arabs] in ‘typical conditions of Nacht und Nebel.’

Stop for an instant. Think of the implications of this term, which Anderson explains as ‘military darkness.’ It shows him right about at least one thing: words can be revelatory.

Nacht und Nebel comes from a Nazi edict of 1941 (with origins in a Wagner opera). Foes within the Reich and deportees from occupied territories were to disappear into ‘Night and Fog’– Nacht und Nebel in German, Nuit et Brouillard in French in the title of Alain Resnais’s renowned film of 1955 about the concentration camps. Anderson rushes to add a rhetorical qualifier, telling readers that, of course ‘in the scales of terror the Nakhba’– Arabic for disaster, the word adopted by many Palestinians for what befell them in 1948/49 – cannot ‘compare’ to the Shoah. The latter was ‘an enormity of a different order.’

Then Anderson compares them anyway. His twists and turns may be summarised like this: Anti-Zionists are really anti-imperialists, not anti-Semites. Yes, the Shoah was atrocious but Zionists were obviously Nazis-lite, which you often cannot perceive through the Nacht und Nebel of 1948-49. Anderson, a comparative historian, does see through it all. Having noted the discrepancy in ‘enormity,’ he makes the Nakhba into Shoah-lite. This accomplished, he can encourage comparisons of Israel to South Africa, commending that the Zionist state be targeted as was apartheid.

By contrast to Anderson, most frank accounts of what Israelis call their War of Liberation, which was fought both against invading Arab League armies and Palestinian Arabs, and what Palestinian Arabs call the ‘Nakhba,’ in which an estimated 700,000 of them became refugees, show real sins committed by both sides.

VI.

A caveat here.

These are difficult, indeed painful times for anyone who (like me) sees rights and wrongs on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian divide. Despair is perhaps the only word to characterise properly the mood of the Israeli left, by which I mean principally the Labor and Meretz parties, and its friends. And this social democratic left is in sorrowful shape, having failed repeatedly to renew itself, having run on intellectual empty for years and having been so brow-beaten by the right that it often fears to use the very word ‘left’.

In the meantime, Israel’s governing rightwing, both its more strictly nationalist and its religious-nationalist components, has ravaged the political culture of the Jewish state as well as of the Jewish world as a whole. Policies that subvert any reasonable Israeli-Palestinian peace play no small role in this. The implications ought not to be underestimated, certainly not by anyone concerned for Israel’s future and who hopes for an Israel-Palestine peace.[8]

Yet this miserable impasse does not justify tendentious reconstruction of history on behalf of a wrong-headed political purpose: the One State solution.

VII.

‘It is difficult,’ writes Anderson of the Palestinians, ‘to think of any national movement that has suffered from such ruinous leadership.’ He is right on this, although I wish he had extended the characterisation to some excited proponents of the ‘Palestinian Cause’ in the West. At least to those who thrill from a distance at violent attacks on ‘the House of Zion’ by ‘resisters’ who shout ‘Death to Imperialism!’ for Western ears but who are really religious militants (like Hamas) who would deny to any non-Muslim population independence within what they deem for theological reasons to be the territory of the ‘House of Islam.’

Religious zealotry is not the whole story. There are Pan-Arabist variants. Last summer Saed Erekat, the new head of the PLO, whose nationalism is ostensibly secular, declared that a Kurdish state in Iraq – or anywhere – would be a ‘dagger’ in the heart of the Arab nation. Why do Palestinians have a right to national self-determination but not Kurds?

Well, perhaps such discrimination is justifiable if you long, as Anderson apparently did in his editorial on the Arab Spring, for a ‘higher idea of an Arab nation’ beyond ‘artificial frontiers’ fashioned by imperialism during World War I. There is, to be sure, nothing wrong with censure of imperial devises. Something is amiss, however, with Anderson’s construction – in a way that is common enough – of the history of Arab nationalism. For him it must, finally, have been a natural development, emerging out of resistance to past Western imperialism. In fact, it emerged initially by harnessing a Western idea (the nation) for opposition to the Ottoman Empire (in the 19th century). Pan-Arabism in another form was allied to Britain against the Ottomans in the famous ‘revolt in the desert’ of World War I. That is, it allied to an imperial power for its own purposes and was betrayed – like Herzl and his political progeny.

So, understanding the Middle East needs to be a little more complex and not condensed to what the Anderson Version declares its key: ‘the unique longevity and intensity of the Western imperial grip on the region over the past century.’ This longevity is another tendentious shortcut and Anderson’s temporal boundary is artificial, even Eurocentric. One need hardly be sympathetic to the historical role of Western imperialism to suggest that ‘Empire’ be situated in the Middle East’s own past (and in relation to the region’s cultures). If you do that, European intrusions become part of a much longer succession of imperial conflicts stretching back in time, for example, to the Mamluk-Ottoman confrontations of the 15th and 16th centuries or the many wars between the Ottoman and Persian Empires from the 16th to 19th centuries.

Anderson’s dogged simplicities also blur the inter-war period (between the First and Second World Wars), when the region was dominated by Western powers, into the ensuing era of newly independent Arab states. World War II becomes something of a detail of history in order to contend that what matters most is that the Americans replaced the British and French as the imperialist power. Hence Anderson’s take on the ‘expedition’ to Iraq in 1941 and the birth of Israel.

It turns out that Anderson’s ‘higher idea’ is the Pan-Arabism that emerged in the 1920s, and was hailed in the 1950s and later by Middle East dictators to the applause of Western Third Worldists. He concedes that it led repeatedly to ruin but seems consoled by its anti-imperialist rhetoric. Where does this bring him?

Early in the Arab Spring, he expressed chagrin that no general strike had materialised throughout the Arab world. His disappointment was natural enough and hardly blameworthy (even if it displayed certain illusions about who was organised and who not). But he was utterly exasperated that there had not yet been ‘a single anti-American or even anti-Israeli demonstration…’ The ‘immediate’ priority of protesters, he advised, as if a T.E. Lawrence of the left, should have been cancellation of the Israel-Egypt peace accord: ‘The litmus test of the recovery of a democratic Arab dignity lies there.’

It’s the shiny object, now in the form of a litmus test for others by someone who hails failed Pan-Arabism – a kind of nationalism – in order to repudiate recognition of a state born of Jewish nationalism. That Israel-Egypt accord, everyone knows, did not resolve all Middle Eastern matters at once but it did end decades of war that took massive numbers of Egyptian (and Israeli) lives. Like his advocacy of a ‘One State Solution,’ consequences for real people are not an urgent factor. After all, he identifies democratic Arab dignity quite explicitly with the ‘impulses’ of Nasserism and the Ba’ath. He does not mention that in power they were both dictatorships that imprisoned and tortured critics.

Was Nasser’s reign less authoritarian and more democratic than that of Mubarak? How? Wasn’t Nasser’s Pan-Arabism always a means to Egyptian power? Was ‘Ba’athism’ simply pan-Arabist and against old, corrupt ruling classes (these latter were real) or was it ‘national socialist’ in the true sense, originating among Arab intellectuals who took to the ideas of the European far right-wing before World War II? What specific features made Ba’ath police states in Syria and Iraq democratic and dignifying for Syrians and Iraqis?

The Anderson Version doesn’t say. His construal of ‘democratic Arab dignity’ doesn’t have too much to do with actual Arabs, their dilemmas, struggles, agonies or hopes. It has nothing to do with any recognisable form of democracy, but only with anti-imperialist rhetoric. Curiously, he brings to mind those Middle East autocrats who responded to their own political failures with the handy cry to the masses: ‘Imperialism!’ ’Palestine!’

VIII.

What does Anderson suggest so far as Jews are concerned? How, finally, does he actually approach modern Jewish history?

He explains that ‘historically’ there were no ‘Jewish critiques of Judaism comparable to radical Enlightenment demolitions of Christianity, once barriers around the ghetto fell, when emancipated Jewish minds typically joined secular debates in the still-Christian world, ignoring their own religion.’

By making the fall of the ghettos his temporal starting point he again can take a short cut – this time past Spinoza’s influential critique of the bible two centuries earlier. To do otherwise would have required some serious study of Jewish intellectual history, including perhaps how Jewish thinkers later discussed Spinoza or deliberated about a ‘Science of Judaism’ in the 19th century.

Anderson hasn’t actually read Zionist literature – which is suffused by critiques of Judaism, most famously perhaps in the writings of Micah Yosef Berdichevsky or Yosef Hayyim Brenner. Their critiques would not be helpful to his case because they don’t reach his conclusions. Anderson has his convenient authorities, like the late Israel Shahak. He lauds this anti-Zionist professor of chemistry at Hebrew University whose writings on Jewish history have long been dismissed by serious scholars as comparable to alchemy.

The radical critique that interests Anderson is obviously that of the young Marx, during debates in the early 1840s. While Marx supported Jewish political emancipation he repeated catch-phrases characteristic of Christian Jew-hatred but translated them into anti-capitalist language. Secularised, the Jewish God was gold, he wrote. Since ‘huckstering’ was the ‘empirical essence of Judaism’ it was evident that ‘the social emancipation of the Jew’ required ‘the emancipation of society from Judaism.’

If Christianity required Jews to give up ‘particularity’ to be saved, Marx demanded an end to their ‘empirical essence’ to be human. Take such abstract universalism to a 21st century conclusion and like Anderson you can demand a ‘One State Solution’ ending the Jewish state.

Of course the 19th century also intrudes. Anderson explains that ‘sociologically,’ European Jewry was then ‘bifurcated’ between those oppressed in the East, and those in the West, which ‘included not only many members of the prosperous middle class … but some of the greatest fortunes on the continent.’ On one end, then, was ‘the shtetl’ of ‘Chagall and Martov,’ and, at the other, ‘the haute finance of the Rothschilds and Warburgs or the career of Disraeli….’

While he acknowledges that ‘the shadow of anti-Semitism fell on them all,’ he doesn’t mention how much anti-Semitism’s expression transcended categories of left and right. August Bebel, the turn of the century German Social Democrat who saw this clearly, felt it urgent to denounce roundly for the ‘socialism of fools’ those anti-Semites who raged about ‘Jewish’ capitalists or bankers. Likewise when French socialist Jean Jaurès rallied to Dreyfus and affirmed that the left had to combat all bigotry, his moral intelligence contrasted to the position of his ‘orthodox’ Marxist colleague, Jules Guesde, who dismissed Dreyfus as a bourgeois captain – whose ‘Affair’ distracted the left from ‘real’ concerns.

Anderson is Guesde-like. It is not just a matter of his slips; all historians make them. Sometimes, however, slips reveal uncritical habits of mind – or a will to stereotypes. Consider what appears to be a small gaffe, making Marc Chagall and Julius Martov representatives of the ‘shtetl.’

A shtetl was a small market town that harbored a Jewish population, usually quite poor. Chagall, however, came from a small but relatively cosmopolitan provincial city (Vitebsk) not all that far from Moscow. Was Anderson perhaps taken by images on – the nostalgic modernism of – Chagall’s canvasses? Or is there more to it?

How does an historian who edits New Left Review call Martov (née Tsederboym), the foremost Russian Marxist critic of Lenin, the product of a shtetl? Has he mistaken him for a character in Fiddler on the Roof? True, Martov was ushered by his Marxism from early Jewish concerns, but he was born in Istanbul, spent his youth in Odessa, and moved to Petersburg. His father directed a steamship company and was a product of the Haskalah – the Jewish ‘Enlightenment’ movements of which Anderson is either blissfully or wishfully unaware. They sought to rethink and recast Jewish culture.

A biographer remarks that Martov’s father had entrée into ‘high society.’[9] This was not entirely unusual for better-off urban Jews in Russia. Anderson seems to know as much about the historical sociology of Eastern Europe’s Jews as about Western ones; the vast majority of these latter lived in pretty modest circumstances.

What is important for Anderson is to present those Jews in the West who were well-to-do as the Zionist lobby avant la lettre. Their resources, after all, gave ‘an entrée to ruling circles of an imperialist Europe beyond the dreams of any other oppressed nationality.’

What luck for Herzl. But perhaps he should have turned to Bolshevism. That, it seems, would be the ultimate conclusion to draw from Anderson. Well, not for Herzl himself, since he died in 1903, but for all other Jews, certainly in that year of more, widespread anti-Jewish violence throughout the Russian empire.

It was also in that year that Bolshevism crystallised at a congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. The fierce quarrel that occurred at that Congress on the Jewish problem is not discussed by Anderson but it deserves mention here because of its implications for the Anderson Version and a future engagement between a left that learns from its past failures and Jews. And because next year is the centenary of the Russian Revolution.

The Jewish Labor Bund, a robust component of the left, contended that a socialist response to the persecution of minorities required both internationalist principles and specific attention, including a distinctive status for itself within the party. Lenin and Martov united against the Bund on the grounds that there could be only one kind of party member. The Bund’s demands were for them (and followers) too particularistic. Martov’s biographer asks,

What could have been more paradoxical than the spectacle of Great Russians, russified Jews, and Russified Georgians all combining at a Socialist Congress in the short breathing spell between the Kishinev pogrom and the pogroms of Gomel and Odessa to fight manifestations of nationalism and chauvinism among … Jewish socialists?.[10]

But the Bund and Martov were allied in their opposition to Lenin’s ‘centralism,’ which they deemed inevitably undemocratic. Lenin, shrewdly, pushed first for a vote against the Bund and won. When it walked out, he had a ‘majority’ to impose his concept of a party over Martov’s protests.

Bolsheviks would surely have said they were anti-Bundist but not anti-Semitic. I don’t mean that facetiously. They weren’t anti-Semites (well, maybe some were) but they were undemocratic.

What we see here is that the discarding of democratic concerns and pluralism came in the same historical context as dismissal of Jewish concerns by part of the left. Since the Bund was anti-Zionist, this suggests a problem that runs deeper than scorn for Herzl’s pursuit of a Great Power.

After all, imagine that African-American socialists at the turn of the twentieth century responded to a wave of lynching with a demand to comrades for particular redress on behalf of their people. Imagine ‘internationalist’ socialists characterising their demand as too narrow-minded, ‘nationalistic’ or ‘chauvinistic.’ Those African-American socialists might well have replied: we don’t trust you.

Historically speaking, a Zionist left emerged in the half decade after that Russian Social Democratic Congress. It led the way to Zionist statehood in 1948. Think of the twentieth century, not just the Third Reich and Stalinism (although they do loom large), and ask yourself if its worries were valid. Read Anderson and ask if today’s compromising Israeli and non-Israeli social democrats who reject a ‘One State Solution’ are right to do so. Medieval Muslim jurists, as he knows, divided the world between the ‘House of Islam’ and the ‘House of War.’ Permanent war was to continue until the latter submitted to the former. This mindset, updated, is obviously amenable to Perry Anderson, as he makes evident from his title, ‘House of Zion.’

A credible left can – a trustworthy left must – do better than that.

[1] I quote in the following these articles by Perry Anderson, all in New Left Review: ‘The House of Zion’(November-December, 2015); ‘On the Concatenation in the Arab World’(March-April 2011); ‘Scurrying Towards Bethlehem’(July-August 2001); ‘Renewals’(January-February 2000). All are available on line at https://newleftreview.org/authors/perry-anderson

[2] Herbert Butterfield, The Whig Interpretation of History (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1965), pp. 30, 52-3, 63.

[3] Butterfield, p. 52.

[4] Deutscher in Perry Anderson, ‘The Legacy of Isaac Deutscher,’ Zone of Engagement (London and New York: Verso Books, 1992), p. 71.

[5] Anderson, ‘The Legacy of Isaac Deutscher’, p. 61.

[6] For examples of collaboration between the Axis and the Arab world see especially Howard M. Sachar, Europe Leaves the Middle East (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1972).

[7] He said this in an interview in a leading Egyptian newspaper. See it translated in David Barnett and Efraim Karsch, ‘Azzam’s Genocidal Threat,’ Middle East Quarterly, Fall 2011; on line at http://www.meforum.org/3082/azzam-genocide-threat.

[8] Since prospects for a fair peace are so grim, I have suggested that an alternative path be sought, at least for the time being. While it would now require some modifications, this is laid out in the series, ‘DD versus Bibi.’ In March 2015, available at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mitchell-cohen.

[9] Israel Getzler, Martov: A Political Biography of a Russian Social Democrat (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1967), p. 2.

[10] Getzler, pp. 60-61.

Well yes

But actually what possibly is the point/effect of this academic feud on the unfolding tragedy of the Occupied Territories etc.?

Even if everything both sides say are true/false?