Australia and Israel are superficially the oddest of couples. They are geographically distant, and massively different in size. Although both were formerly ruled by Britain, their cultural heritages are radically different. Australia remains strongly Anglo-Saxon even if modified by a more recent multicultural framework, whilst Israel contains a diverse blending of Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews and Arabs. Additionally, Australia is one of the most peaceful countries on earth whilst Israel sits in the middle of a regional war zone

Yet, oddly, a number of linked factors have brought these countries together including a highly Zionistic Jewish community in Australia which has resulted in a particularly high rate of Aliyah to Israel, an increasing number of Israelis moving to Australia, and importantly the supportive role that the Australian Labor Party government (via its Foreign Minister Dr H.V. Evatt) played in the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. With the exception of a brief period from 1972-75 whilst Gough Whitlam was Prime Minister, Australia and Israel have generally enjoyed friendly relations.

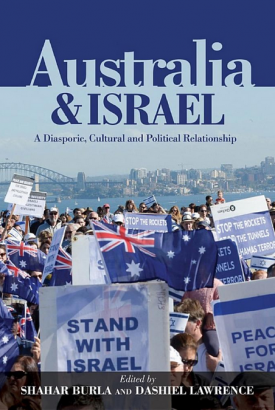

In their new edited book, two emerging Australian academics, Shahar Burla who is an ex-Israeli Jew and Dashiel Lawrence who is a non-Jewish Australian, present a diverse range of topics and perspectives on the Australia-Israel relationship. Chapters cover a wide range of themes including Australian Jewish pro-Israel advocacy; the place of Hebrew and Israel education in Jewish schools; the role of Israelis in Australia; the sad death of dual-national Ben Zygier; the attitude of Australian political parties such as the Labor Party and Greens to Israel; and the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. (Full disclosure; I contributed a chapter to this book.) As in any edited collection, there are some stronger and some weaker contributions. Overall, they paint a more ambiguous relationship between the two countries than might otherwise be assumed.

Co-editor Dashiel Lawrence provides an insightful analysis of changing Australian Jewish connections with Israel. He argues that Australian Jewry have shifted from an old top-down model whereby traditional Zionist leaders imposed a rigid pro-Israeli government (and more often than not pro-Likud) view on the community, to a far more fluid and decentralised model enabling a group of independent and often localised Jewish networks to express a diverse range of views on the Middle East. He notes that whilst these views tend to endorse two states for two peoples and are sometimes very critical of Israeli government policies towards the Palestinians, they are often far more effective than establishment pro-Israel advocacy groups in combating extreme anti-Israel opinions. Whilst the groups Lawrence examines mainly lean to the left, he could perhaps have extended his study to newer conservative Jewish groups in broadcast and social media which are also critical of the official communal perspective.

Book co-editor Shahar Burla adds to Lawrence’s arguments by critically exploring the Australian Jewish community’s advocacy around the June 2010 Gaza Flotilla Raid. He argues that Israeli government bodies provided a form of ‘Hasbara’ propaganda that was directly used by leadership organisations in their attempts to mobilise the community for advocacy activities. But, in his opinion, this propaganda comprised conservative and outdated narratives which do not match the more diverse views of today’s Jewish community, and consequently was relatively unsuccessful in convincing many Jews who do not favour unqualified support for Israeli actions.

The joint chapter by educationalists Zehavit Gross (Israeli) and Suzanne Rutland (Australian) also reflects on the challenges posed by increasing ideological diversity. They note that many Australian Jewish children today are more concerned with universalistic themes and causes (e.g. the human rights of refugees or indigenous disadvantage) than with particular Jewish concerns. Further, the curriculum in most Jewish schools presents a highly traditional Zionist perspective on Israel rather than the critical viewpoint favoured by many younger people. They recommend that a more pluralist approach be adopted – one which enables graduates to develop their own Jewish and Israel-linked identity.

Australian-Israeli academic Ran Porat provides a fascinating overview of what he calls the ‘Ausraeli’ identity of the estimated 15,000 Israelis living in Australia. He argues that Ausraelis reject past Zionist binary frameworks that praised immigration to Israel, termed ‘Aliyah’ (ascent), and conversely rejected emigration from Israel as shameful, traditionally labelled ‘Yerida’ (descent). Instead, they have developed a transnational approach to identity which incorporates strong linguistic and cultural links with their former homeland. Most retain dual citizenship, still call themselves Zionists, and are strong political supporters of Israel. Yet at the same time they hold a negative view of Israeli society today, and a serious pessimism about its prospects. One additional item that Porat might usefully have added here was a survey of their political views and/or voting intentions in regards to Israeli politics, and whether distance turns them into greater hawks or doves.

Masters graduate Alex Benjamin Burston-Chorowicz provides a comprehensive historical and political analysis of the (mostly) ups and downs of Australian Labor Party attitudes to Israel. He documents that the party was highly supportive of Israel from 1948, that the party suddenly shifted to a so-called ‘even-handed’ policy (regarded by many Jews as pro-Arab) whilst in government from 1972-75, and then returned to a largely pro-Israel policy moderated by occasional bouts of criticism.

At times he misses some nuances and key historical events. For example, he seems unaware of British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin’s intense hostility to the creation of Israel and to Jews per se. He also fails to mention Labor Party Prime Minister Bob Hawke’s contentious comparison of Israel to apartheid South Africa in a May 1988 speech to a Jewish audience which is analysed at length in the new book Let My People Go (Hybrid Publishers, 2015) by Sam Lipski and Suzanne Rutland. He also arguably exaggerates the differences between the recent Labor Prime Ministers Kevin Rudd (described as critical of Israel) and his successor Julia Gillard (portrayed as unconditionally supportive of Israel). It was the Rudd government which passed a formal Parliamentary resolution in 2008 celebrating and commending the achievements of the State of Israel over 60 years, and a shared common commitment by Australia and Israel to civil and human rights and cultural diversity.

But he is right to note there are significant structural factors which are driving a shift in the Labor Party to a more critical perspective on Israel. One is the increasing electoral influence of Arab immigrants in Labor held seats in Western Sydney. The other is the rightward shift in Israeli politics, and the associated international perception that a Netanyahu-led Israel is no longer serious about a two-state solution.

I found two of the chapters problematic. Australian-Palestinian PhD candidate Micaela Sahhar, who seems to be a supporter of the BDS movement, attempts to identify the commonalities between Australian and Israeli military myths. But her analysis is based on the simplistic discourse framed by the French Jewish Marxist Maxime Rodinson in the early 1970s (also notorious for his early 1950s apology for Stalinist anti-Semitism at the time of the Slansky Trial and the Doctors Plot) that Israel is a settler-colonial state similar to Australia based on the dispossession by European settlers of an indigenous population. As sensibly noted by Fania Oz-Salzberger in the same volume, Rodinson and Sahhar ignore that most European Jewish refugees were not part of a colonial population akin to British immigrants to Australia or India, but rather saw themselves as returning to their historical land; a significant number of Jews were indigenous to Palestine; and the majority of Israeli Jews today came from Middle Eastern countries.

This contentious framework leads Sahhar to use loaded and undefined terms such as ‘stolen land’ (but which land and stolen from whom?), and to draw odd ahistorical connections between Australian participation in the 1917 Battle of Beersheba and a 2014 statement by the coalition government suggesting (wrongly in my opinion) that Israel’s West Bank settlements are not illegal. Even odder is the fact that the published references for this chapter are incomplete, and that at least one of the cited authors is a well-known anti-Jewish (as well as anti-Israel) conspiracy theorist.

Equally concerning is the chapter written on, but totally failing to critically examine, the BDS movement, by two Australian academics Ingrid Matthews (who calls herself a supporter of BDS) and James Arvanitakis (who describes himself as a supporter of the right to BDS who nevertheless chooses not to join the campaign). This one-sided chapter presents a number of pro-BDS statements that have been debunked elsewhere (see Mendes and Dyrenfurth, Boycotting Israel is Wrong, New South Press, 2015).

These include the claim that its aim is peace (in fact its aim is the elimination of the State of Israel and its replacement by an Arab majority state of Greater Palestine); that it only attacks institutions not individual academics (in fact there are numerous examples of the black-banning of individual Israeli scholars); and that it rejects any form of racism including anti-Semitism (in fact there are numerous examples of hate speech emanating from the BDS movement in Australia and elsewhere including a specific defence of anti-Semitism as ‘honourable’ by sacked US academic Steven Salaita who is implicitly praised in this chapter).

The authors also seem unaware that there is a large gap between defending Israel’s right to exist and providing unqualified support for Israeli policies; that Jews are not the only ethno-religious advocacy group that influence Australian government attitudes towards Israel; and that moderates on both sides of the Israel-Palestine debate require much resilience to cope with attacks by Greater Palestine or Greater Israel extremists.

In contrast, Israeli academic Fania Oz-Salzberger, who has spent considerable time in Australia at Monash University, argues in her concluding summation against the censorship proposed by the BDS movement, and in favour of ongoing dialogue with a wide range of opinions. She emphasises that many Zionists are critical of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, and supportive of Palestinian national rights via a two-state solution.

Overall this is a thought-provoking volume which adds considerably to existing knowledge on Israeli-Australian relations. But, as other reviewers such as Nick Dyrenfurth have already noted, there are additional topics that might be usefully explored in a further volume, such as the attitude of the conservative Liberal Party; an empirical analysis of Australian Jews (and their core lobby groups) as a pro-Israel advocacy community; and an assessment of the often close relationship between Australian and Israeli trade unions.